This week’s parasha, Terumah, describes the construction of the mobile sanctuary, the Mishkan. While the Mishkan was designed to accompany the Israelites in their travels, the Haftarah for this week’s parasha describes how King Solomon finally built the permanent holy sanctuary in Jerusalem, the Beit haMikdash. The Haftarah tells us that the Temple “was built of stone finished at the quarry, and there was neither hammer nor axe nor any tool of iron heard in the house, while it was in building.” (I Kings 6:7) God did not permit the use of iron tools in constructing the Temple, for iron is an implement of war, and the Temple was a house of peace. So, how were the builders able to cut the stones without any iron tools?

The simplest explanation is that the stones were cut “at the quarry”, as the verse above states, and iron tools were only forbidden “in the house” itself. When God commanded not to use “hewn stones” for the altar (Exodus 20:23), it only meant not to cut the stones or bring iron tools directly onto the holy Temple Mount. The stones could, however, be cut elsewhere and brought to the Temple Mount. This suggestion is further supported by I Kings 5:31, where we read that “The king [Solomon] ordered huge blocks of choice stone to be quarried, so that the foundations of the house might be laid with hewn stones.”

Having said that, Jewish tradition holds that the stones for the Temple were cut entirely without the use of iron implements. Instead, our Sages teach that King Solomon had a unique tool called a Shamir, described as some kind of “worm” or “stone” that was able to penetrate even the toughest materials with laser-like precision. What, exactly, was the Shamir, and what might modern science reveal about this mysterious object?

Shamir in Tanakh and Talmud

The earliest source to mention the Shamir is the prophet Isaiah. In foretelling the destruction of Jerusalem, he said how the city “will be a desolation, it will not be pruned or hoed, and it shall be overgrown with shamir and thistles…” (Isaiah 5:6) This suggests that the Shamir is something organic and can grow. The notion is confirmed by the next source that discusses it, Jeremiah, who proclaimed that “The sin of Judah is inscribed with an iron stylus, engraved with tzipporen shamir…” (Jeremiah 17:1) Here we see the Shamir described as a tzipporen, loosely translated as a “fingernail” or “talon”. Again, it implies something organic, as opposed to the iron stylus it is juxtaposed with in the same verse.

We next see the Shamir in God’s message to the prophet Ezekiel, when He tells Ezekiel that He will make him like the Shamir, “harder than flint” (k’shamir chazak mitzor). Here we learn the Shamir is a substance of incredible strength. Rashi comments on this verse that the Shamir is a worm that splits rocks, or perhaps a type of hard flintstone, or even a particularly strong alloy of iron. The final direct mention of Shamir in the Tanakh is in Zechariah 7:12, where the nation is said to have hardened their hearts like the Shamir.*

Next, we learn in the Mishnah that God created ten special, mystical things on the eve of the first Sabbath, at the very end of Creation (Avot 5:6). In this list is included the miracle-working staff of Moses, the Two Tablets of Law, and the Shamir. Rabbi Ovadiah of Bartenura (c. 1445-1515) comments here that the builders would draw a line on a stone, and the Shamir worm would crawl along the line and split the stone. He also points out that it was with the Shamir that Moses created the choshen and ephod, the Priestly Breastplate, and engraved the names of the Tribes of Israel into the precious stones on that breastplate. The source for this is the Talmud:

In Gittin 68a, we learn that Solomon was unsure of how to build the Temple without iron tools, and consulted with the Sanhedrin at the time. They told him: “There is a Shamir that Moses used to cut the stones for the ephod.” Solomon then asked the Sages where to find the Shamir, and this leads to a lengthy story about how he acquired it. (In fact, this is the longest story in the whole Talmud!) The puzzling narrative requires an in-depth analysis of its own, and is beyond the scope of the present discussion. Suffice it to say that it involves the great warrior Benayahu ben Yehoyada, a confrontation with Ashmedai, the “prince of demons”, and the angelic “Prince of the Sea”.

The Midrash (Yalkut Shimoni II, 182) has a slightly different account: Solomon knew how to speak to animals (I Kings 5:13), and he asked them where the Shamir might be found, at which point an eagle flew to the Garden of Eden and brought it to him! He then asked the Sages how to use the Shamir, and they directed him to Ashmedai. The Midrash also notes that the Shamir was so powerful it had to be wrapped in wool and kept in a special lead box filled with barley. The same teaching is found in the Talmud (Sotah 48b), too, where we also learn that the Shamir was the size of a barley grain, and that it ceased to exist following the destruction of the First Temple.

The big mystery is how the tiny Shamir, whether a “worm” or a “stone”, was able to penetrate hard substances and cut them with laser-like precision. While one could simply relegate this to a miracle, we generally hold that even God works through derekh hateva, natural ways, in most cases. Could there be a scientific explanation for the Shamir? Thankfully, our Sages left us a major clue that might help solve the mystery.

Shamir in Science

Our Sages taught that the Shamir had to be kept specifically in a box of lead to avoid danger. We have all probably received an x-ray exam at some point in our lives, and the technician always makes sure to put a lead jacket on the parts of the body not being scanned. This is because lead is an excellent blocker of dangerous radiation. This little detail strongly suggests that the Shamir was likely radioactive. Perhaps it used some kind of high-energy radiation to cut through stone. In fact, today we have nuclear-pumped lasers which use radioactive uranium fragments to create ultra-powerful light rays. Though such lasers are not commercially available at the moment, they have been proposed for use in manufacturing for precision deep-cutting and welding!

(Interestingly, renowned Jewish physicist Edward Teller, often called the “father of the hydrogen bomb”, proposed using such nuclear-pumped lasers in a space defense system that would shoot down enemy nuclear missiles. His “Project Excalibur” was soon scrapped and never realized.)

And then there’s the lithoredo. In 2019, scientists in the Philippines discovered a new species of shipworm, named Lithoredo abatanica. Unlike other shipworms which eat and bore into wood, the lithoredo eats and bores into limestone! They have special tiny teeth to grind away rock. Here is a worm that is actually able to eat through stone, and quite precisely, too. Could the Shamir have been a special version of the lithoredo, or a related species that is now extinct?

There is another tiny organism on the planet that is bizarrely able to withstand incredible conditions, including deadly radiation, dehydration, and even the freezing vacuum of outer space. This organism is the tardigrade, also known as a “water bear”. The hardiest creature on the planet, it can suspend its metabolism and literally go decades without any food or water at all. Uniquely, the DNA of tardigrades is protected by a special protein that blocks radiation, allowing them to survive levels of radiation hundreds of times greater than what would be lethal for humans. Could the Shamir have been some kind of special hybrid organism with qualities of both the tardigrade, capable of living many decades and withstanding immense radiation; and of the lithoredo, able to eat, digest, and cut through stone? Did the Shamir contain radioactive material in its body, or generate something laser-like? It is certainly within the realm of the scientifically-possible.

Ultimately, we may never know the true nature of the Shamir, for there are those who hold the future Third Temple will not require the Shamir in its construction. The Lubavitcher Rebbe, for instance, taught that since in the messianic era “swords will be beaten into plowshares” (Isaiah 2:4), iron will no longer be considered an implement of war and will therefore be allowed in the building of the Third Temple. Others hold that the Third Temple will not require building at all, and will descend fully-formed from the Heavens (see Rashi at the end of Sukkah 41a). Whatever the case might be, may we merit to see it speedily and in our days!

*For Marvel comics fans: the word shamir was translated into Greek as adamas, and then to Latin as adamans, and to English as “adamant”, the origin of “adamantium”, that super-hard element injected into Wolverine’s skeleton, and that made up the body of Ultron. (For more on Judaism and comic books, see here.) The Shamir was also the inspiration for the adopted last name of Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir.

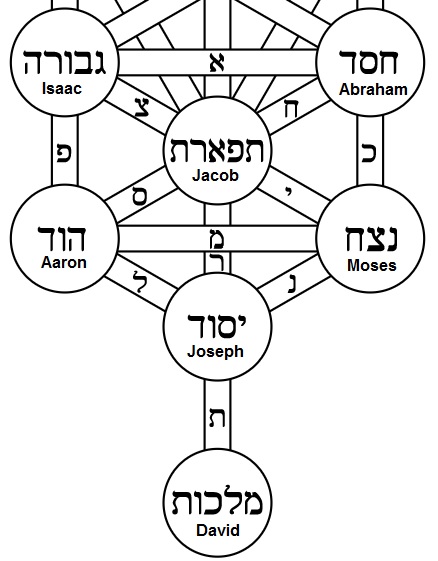

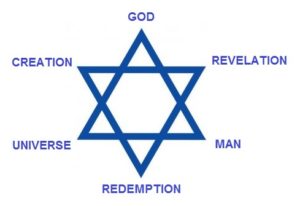

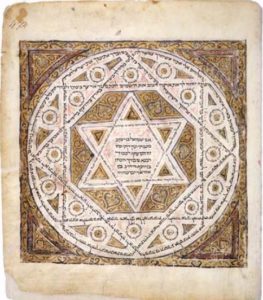

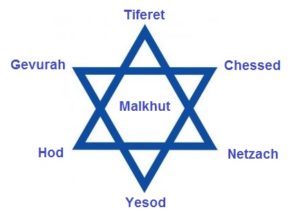

This arrangement of seven (or more specifically, of three-three-one) is found within the Menorah, too, that most ancient of Jewish symbols. For this reason, some argue that the opinion of the Shield of David having the Menorah and the opinion of it having the hexagram are really one and the same. They both reflect a divine geometry of 3-3-1. The sefirot are arranged in the same 3-3-1 manner, and corresponding to them are the seven shepherds of Israel: Chessed, Gevurah, and Tiferet parallel the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; Netzach, Hod, Yesod parallel the next three great leaders of Moses, Aaron, and Joseph; and Malkhut (“Kingdom”) naturally stands for David. David is at the centre of the star, so it is fitting that the star is named after him.

This arrangement of seven (or more specifically, of three-three-one) is found within the Menorah, too, that most ancient of Jewish symbols. For this reason, some argue that the opinion of the Shield of David having the Menorah and the opinion of it having the hexagram are really one and the same. They both reflect a divine geometry of 3-3-1. The sefirot are arranged in the same 3-3-1 manner, and corresponding to them are the seven shepherds of Israel: Chessed, Gevurah, and Tiferet parallel the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; Netzach, Hod, Yesod parallel the next three great leaders of Moses, Aaron, and Joseph; and Malkhut (“Kingdom”) naturally stands for David. David is at the centre of the star, so it is fitting that the star is named after him.