This week’s Torah portion is Va’etchanan, which begins with Moses’ many prayers to God, and famously includes both an account of the Ten Commandments, and the Shema. It also happens that this Friday we celebrate the little-known holiday of Tu B’Av (literally, the fifteenth day of the month of Av). Upon closer examination, the parasha and the holiday are quite deeply related.

The Talmud (Ta’anit 26b) states:

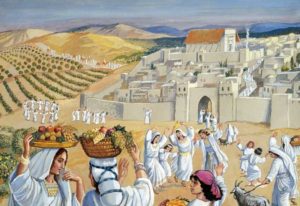

Rabban Shimon ben Gamaliel said: there were no days more joyful in Israel than the fifteenth of Av and Yom Kippur. On these days, the daughters of Jerusalem used to go out in white garments, which they borrowed in order not to put to shame anyone who had none… The daughters of Jerusalem came out and danced in the vineyards exclaiming at the same time, “Young man, lift up your eyes and see what you choose for yourself. Do not set your eyes on beauty, but set your eyes on [good] family…”

Young Ladies Dancing on Tu B’Av (Courtesy: Temple Institute)

In ancient times, Tu B’Av was a day of speed-dating, matchmaking, and engagements. It is easy to see why Tu B’Av has become associated with love and romance, and is often referred to today as a “Jewish Valentine’s Day”. While this is true, a careful reading will reveal that the holiday actually has far more to do with the fact that the daughters of Jerusalem loved one another, going out in the same white garments to avoid shaming each other. Tu B’Av celebrates a much greater power of love, one that holds the cure for the ails of the solemn Tisha B’Av that was commemorated just days earlier.

Why is Tu B’Av Special?

The Talmud (Ta’anit 30b-31a) asks: why does the Mishnah above compare Tu B’Av to Yom Kippur? We can understand why Yom Kippur is a special day – since it was then that God forgave the Israelites for the sin of the Golden Calf and gave a new set of Tablets – but why Tu B’Av? The question is answered with a list of significant historical events that happened on the 15th of Av.

First among them is the day when the prohibition for people of different Israelite tribes to marry each other was repealed. Initially, during the settlement of the Holy Land, people married only within their own tribe to avoid situations where parcels of land might unfairly be transferred to a different tribe. Eventually, this ban was lifted, allowing anyone to marry whomever they wanted. Once again, we see the theme of love associated with Tu B’Av.

The Talmud goes on to list a number of other events, the most salient of which is that on this day, the “generation of the Wilderness ceased to die out.” After the sin of the Spies, God decreed that the Israelites would wander in the Wilderness for forty years until the entire adult male generation passed away. In the fortieth year, the last of that generation passed away on the fifteenth of Av, allowing the nation to finally move on from the sin of the Spies. (Some say the last group of men was actually spared from death on Tu B’Av, turning that day into a celebration.)

Here, the Talmud cites a teaching that ever since the sin of the Spies, God had stopped speaking to Moses directly. Instead, Moses received visions from God just like any other prophet. On Tu B’Av, after nearly forty years, God once more resumed speaking to Moses “face-to-face”. Tu B’Av was the day Moses reclaimed his status as the greatest of prophets, the only one who spoke to God in a fully conscious state.

Where in the Torah do we see that God resumed speaking to Moses in this way? The Pnei Yehoshua comments that this happened in our weekly parasha, Va’etchanan. After Moses’ incessant prayers, God finally reappeared to him. And so, we see yet again the theme of love on Tu B’Av; this time, though, not love between people, but between God and man.

One Love

It is in this week’s parasha that we are commanded to “love Hashem, your God, with all of your heart…” Earlier in Leviticus we were given the mitzvah to “love your fellow as yourself.” While the latter is understandable, how exactly is one supposed to love God? God is the eternal, all-encompassing, omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent force within all of Creation, and everything that infinitely lies beyond. The Kotzker Rebbe once rightly observed that “one who does not see God everywhere, does not see God anywhere.” How does one love such a transcendent Being?

Our Sages teach something incredible. The full verse in Leviticus states, “And you shall love your fellow as yourself, I am Hashem.” Why finish with “I am Hashem”? The verse would have stood well on its own without that last part! The juxtaposition of words can teach us that that loving your fellow is loving Hashem. In fact, the numerical value of the whole verse (ואהבת לרעך כמוך אני יי) is 907, equivalent to “love Hashem, your God” (ואהבת את יי אלהיך)! If God is found within each person, and within each creation, then loving every person and every creation is loving God.

This is all the more important on Tu B’Av which, not coincidentally, comes immediately after Tisha B’Av, a day commemorating a Temple destroyed because of sinat chinam, baseless hatred, and absence of love between fellows. When the Jews of the Second Temple period stopped loving each other, it was clear that they had stopped loving God, and God destroyed His Temple.

Tu B’Av is the antidote to Tisha B’Av. It is quite ironic that while many mourn and wail on Tisha B’Av, few pay much attention to the far more significant message of Tu B’Av. It is Tu B’Av that should be carefully observed and loudly celebrated. After all, the Mishnah goes so far as to place Tu B’Av on the same pedestal as Yom Kippur! That makes it even more ironic, as the majority of Jews observe Yom Kippur in some way, yet have little knowledge of Tu B’Av which, in reality, is just as important as Yom Kippur, and perhaps even more so:

The Mishnah ends by suggesting that while the Temple was destroyed on Tisha B’Av, it will be rebuilt on Tu B’Av, for just as the “daughters of Zion” would go out on Tu B’Av, they will go out once more in the “day of the building of the Temple, may it be rebuilt speedily and in our days.”

The article above is adapted from Garments of Light – 70 Illuminating Essays on the Weekly Torah Portion and Holidays. Click here to get the book!