This week’s parasha, Toldot, begins with a focus on Isaac, now forty years old and finally married. Commenting on this, the Zohar says some incredible things. Embedded here in the Zohar is a deeply mystical text known as Midrash HaNe’elam, “the Hidden Midrash”. It is both an integral part of the Zohar (with others sections of it peppered throughout the Zohar’s many volumes) and a distinct work with its own flavour. It, too, dates back to the 2nd century CE teachings of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. Midrash HaNe’elam explains that Isaac was “brought back to life”, so to speak, by his wife Rebecca. How so? Continue reading

Tag Archives: Toldot (Parasha)

Itzchak and the Kibbutz: Transforming Israel

This week’s parasha, Toldot, is the only one in the Torah that speaks at any length about Isaac. Abraham is introduced at the end of parashat Noach, is the protagonist of Lech Lecha and Vayera, and concludes his story in Chayei Sarah. Isaac, on the other hand, is only briefly discussed in Vayera, reappears only at the end of Chayei Sarah, and fairly quickly makes his exit in this week’s parasha (appearing just once more in Genesis 35, when he passes away). Thereafter, Jacob becomes the subject in the next few parashas. Of the three patriarchs, Isaac is least spoken of—by far.

What we are told of Isaac is that he was a diligent worker; digging wells, sowing seeds, and turning the barren lands of Israel into flourishing oases:

And Isaac sowed in that land, and found in the same year a hundred-fold; and God blessed him. And the man waxed great, and grew more and more until he became very great. And he had possessions of flocks, and possessions of herds, and a great household; and the Philistines envied him. Now all the wells which his father’s servants had dug in the days of Abraham his father, the Philistines had stopped them, and filled them with earth. And Avimelekh said unto Isaac: “Go from us; for you are much mightier than we!” … And Isaac dug again the wells of water… (Genesis 26:12-18)

Reading this passage, one can’t help but sense a certain familiarity with this narrative. A Jew comes to work a difficult land, and finds great prosperity. The Philistine becomes jealous, and seeks to expel the Jew from the land. Instead of trying to build up his own prosperity, the Philistine instead wastes time and effort trying to sabotage the Jew. When this doesn’t work, and the Philistine feels powerless, he continues to protest and shout at the Jew: “Go from us; for you are much mightier than we!” All along, the Jew quietly perseveres, and re-digs the wells. This is the story of Isaac and the Philistines; it is the story of modern Israel and the Palestinians.

In fact, of all the patriarchs and biblical figures, it is Isaac that is most associated with the land of Israel. He was the only patriarch never to leave the Holy Land, spending his entire 180-year lifespan there. The Torah says little of Isaac except for his diligent love and labour of the land. Of course, as we read at the start of the parasha, Isaac and Rebecca literally produced Israel—their son, that is. Every child is the product of three partners: father, mother, and God. Beautifully, the gematria of “Isaac” (יצחק), his wife “Rebecca” (רבקה), and God’s Name (יהוה) add up to 541, the value of “Israel” (ישראל). And just as it was the labour of Isaac and Rebecca that produced the boy Israel, it was their labour that first transformed the land of Israel.

Our Sages explain that the reason Isaac isn’t discussed very much in the Torah is because he actually did not complete his mission (see, for instance, Ba’al HaTurim on Deuteronomy 7:21). The Arizal further notes that the name “Isaac” (יצחק) is an anagram of קץ חי, meaning that his spirit will “live again at the End of Days” (Sha’ar HaPesukim, Lech Lecha). And this is precisely the spirit that guided and infused the Jewish pioneers who re-established modern Israel.

Like Isaac, these pioneers came to a completely barren land. It is worth recalling that when Mark Twain visited the Holy Land in 1869, he wrote:

A desolation is here that not even imagination can grace with the pomp of life and action… We never saw a human being on the whole route… There was hardly a tree or a shrub anywhere. Even the olive and the cactus, those fast friends of the worthless soil, had almost deserted the country… Of all the lands there are for dismal scenery, I think Palestine must be the prince… Can the curse of the Deity beautify a land? Palestine sits in sackcloth and ashes. Over it broods the spell of a curse that has withered its fields and fettered its energies. (The Innocents Abroad)

Similarly, when President Ulysses S. Grant visited in 1878 (becoming the first American president to do so), he described nothing but misery and poverty, concluding that the entire trip was “a very unpleasant one”. Who would ever think that less than a century later, Israel would be a prosperous, flourishing Middle Eastern powerhouse?

When we think of the re-establishment of Israel, we often think of those statesmen and warriors: Herzl and Weizmann, Ben-Gurion and Jabotinsky, Golda Meir, Moshe Dayan, and so on. But the real heroes were those simple Jews who made aliyah against all odds, sacrificing everything they had, working tirelessly to turn a desert into a sanctuary. Like Isaac long before them, they drained swamps and dug wells, sowed seeds and irrigated the land. And soon, like Isaac, they found me’ah she’arim, “hundred-fold” blessings.

Today’s Jerusalem neighbourhood of Mea Shearim was founded in 1874 by a group of religious Jews, at this very time during the week of parashat Toldot, where the name of the neighbourhoud comes from. We often forget that the first Jewish groups to make aliyah were deeply religious folks who yearned to return to the Holy Land, and to usher in the Final Redemption. Long before the Zionist movement, Rabbi Yehuda HaHasid Segal (c. 1660-1700) brought some 1500 Jews to Jerusalem in 1697. Eighty years later, Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk (c. 1730-1788), one of the early Hasidic leaders, led a group of 300 Jews. In 1808, Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Shklov (c. 1750-1827), a disciple of the Vilna Gaon, fatefully brought another 150 Jews. This is not to mention the countless Sephardic Jews who settled in Israel in the 16th century following the Spanish Expulsion. (One of them, Don Joseph Nasi, nearly established a Jewish state then, and was granted the title “Lord of Tiberias” by the Ottomans!) These early returnees paved the way for future waves of larger aliyot.

Starting in 1882, those aliyot were primarily composed of thousands of secular Eastern European Jews. Truly, the word “secular” is inappropriate. While they had, for the most part, abandoned traditional Judaism and the old shtetl mindset, they fervently wished to return to their Biblical home, reclaim their Biblical language, work their God-given land, and reinvigorate the Jewish people. It was Rabbi Avraham Itzchak Kook (1865-1935) who best understood them.

Rav Kook never critiqued these pioneers, and recognized their old frustrations and resentments. He would say that they were not rebelling against the Torah, but against galut. They were tired of being weak, poor, and downtrodden; exiled and persecuted. He would say that, indeed, Jews had forgotten that they not only possessed a holy soul, but also a holy body. And he would point out that the work of these pioneers—draining swamps, digging wells, sowing seeds—was also holy work, and a fulfillment of the Torah. This is the work of Isaac, described in Jewish mysticism as the very embodiment of Gevurah, “strength”. Gevurah is associated with fire and passion, with self-sacrifice and perseverance, with working hard and overcoming challenges. This is a fitting description of Isaac and—political leanings aside—every one of those early Jewish pioneers. They were all, as Rav Kook described it, “a fiery spirit encased in powerful muscles.”

That these pioneers organized themselves into kibbutzim is no coincidence. In his Eros and the Jews, historian David Biale points out that the earliest origin of the word “kibbutz” is from the Tzfat Kabbalists of the 16th century! These kibbutzim referred to holy, mystical gatherings, with the ultimate aim of hastening the Redemption. Later on, Hasidim would adopt the term to refer to their own religious gatherings. Biale notes how Breslover Hasidim in particular would refer to their congregation as hakibbutz hakadosh. (See pgs. 118 and 270, with footnotes.)

Certainly, the secular kibbutz could not be described as “religious”, but it definitely had a mysticism to it, and the very same goal of hastening the redemption of the Jewish people. More than anything else, it was the kibbutz that made modern Israel possible. It was the kibbutz, through unceasing collective labour and brotherly unity, that transformed a wasteland into a haven. To this day, Israel’s kibbutzim still produce 10% of its total industrial output (some $8 billion in wealth), and a whopping 40% of its agriculture! Needless to say, Hasidic Jews in Mea Shearim would have had little to eat without kibbutznikim in Degania.

These kibbutznikim still carry the spirit of Isaac, the very first hard-working agrarian, shepherd, hydrologist Jew who tirelessly worked the land of Israel to make it flourish with meah she’arim. And so, it may not be much of a stretch to point out that the gematria of “Isaac” (יצחק) is 208, exactly equivalent with “kibbutz” (קיבוץ). Our Sages explained that the Torah speaks so little of Isaac because his task was not finished. They prophesied that the spirit of Itzchak would return at the End of Days, ketz chai, to complete his work. How fortunate are we to see this prophesy realized right before our very eyes.

Shabbat Shalom

Marriage and Prayer: Why They Are the Same, and How to Succeed in Both

This week’s parasha is Toldot, which begins:

And these are the genealogies [toldot] of Isaac, the son of Abraham; Abraham begot Isaac. And Isaac was forty years old when he took Rebecca… for a wife. And Isaac prayed to Hashem opposite his wife, because she was barren, and Hashem accepted his prayer, and Rebecca his wife conceived.

The Torah juxtaposes Isaac’s marriage to Rebecca with Isaac’s successful prayer. One of the Torah’s central principles of interpretation is that when two ideas or passages are placed side by side, there must be an intrinsic connection between them. What is the connection between marriage and prayer?

Another central principle of interpretation is that when a word or concept appears for the first time in the Torah, its context teaches the very epitome of that word or concept. The first time that the word “love” is used between a man and woman in the Torah is with regards to Isaac and Rebecca, and the two thus represent the perfect marital bond (a topic we’ve explored in the past; see: ‘Isaac and Rebecca: the Secret to Perfect Marriage’ in Garments of Light).

So, we see that Isaac and Rebecca were very successful in their love and marriage, and simultaneously very successful in their prayers. In fact, our Sages teach that when the Torah says “Isaac prayed… opposite his wife”, it means that the two prayed together in unison, and some even say they prayed while in a loving embrace, face-to-face, literally “opposite” one another. God immediately answered their prayers. What is the secret of Isaac and Rebecca’s success in love and prayer?

Understanding Prayer

It is commonly (and wrongly) believed that prayer is about asking God for things. Not surprisingly, many people give up on prayer when they feel (wrongly) that God is not answering them, and not fulfilling their heartfelt requests. In reality, prayer is something quite different.

A look through the text of Jewish prayers reveals that there is very little requesting at all. The vast majority of the text is made up of verses of praise, gratitude, and acknowledgement. We incessantly thank God for all that He does for us, and describe over and over again His greatness and kindness. It is only after a long time spent in gratitude and praise that we have the Amidah, when we silently request 19 things from God (and can add some extra personal wishes, too). Following this, we go back to praise and gratitude to conclude the prayers.

Many (rightly) ask: what is the point of this repetitive complimenting of God? Does He really need our flattery? The answer is, of course, no, an infinite God does not need any of it. So why do we do it?

One answer is that it is meant to build within us an appreciation of God; to remind us of all the good that He does for us daily, and to shift our mode of thinking into one of being positive and selfless. Through this, we build a stronger bond with God, and remain appreciative of that relationship.

The exact same is true in marriage. Many go into marriage with the mindset of what they can get out of it. They are in a state of always looking to receive from their spouse. Often, even though they do receive a great deal from their partner, they become accustomed to it, and forget all the good that comes out of being married. They stop appreciating each other so, naturally, the marriage stagnates and the couple drifts apart.

Such a mindset must be altered. The dialogue should be like that of prayer: mostly complimenting, acknowledging, and thanking, with only a little bit of request. The Torah tells us that God created marriage so that man is not alone and has a helper by his side. The Torah says helper, not caretaker. We should appreciate every little bit that our spouses do, for without them in our lives we would be totally alone and would not even have that little bit. The Talmud (Yevamot 62a) tells a famous story of Rabbi Chiya, whose wife constantly tormented him and yet, not only did he not divorce her, but he would always bring her the finest goods. His puzzled students questioned him on this, to which he responded: “It is enough that they rear our children and save us from sin.”

A Kind Word

By switching the dialogue to one of positive words and gratitude, we remain both appreciative of the relationship, and aware of how much good we do receive from our other halves. Moreover, such positive words naturally motivate the spouse to want to do more for us, while constant criticism brings about the very opposite result.

Similarly, our Sages teach that when we constantly praise God and speak positively of Him, it naturally stirs up His mercy, and this has the power to avert even the most severe decrees upon us. We specifically quote this from Jeremiah (31:17-19) in our High Holiday prayers:

I have surely heard Ephraim wailing… Ephraim is my precious child; a child of delight, for as soon as I speak of him, I surely remember him still, and My heart yearns for him. I will surely have compassion for Him—thus said Hashem.

Ephraim is one of the Biblical names for the children of Israel, especially referring to the wayward Israelite tribes of northern Israel. Despite the waywardness, Ephraim’s cries to God spark God’s compassion and love for His people.

A kind, endearing word can go very far in prayer, as in marriage. The same page of Talmud cited above continues to say that Rav Yehudah had a horrible wife, too, yet taught his son that a man “who finds a wife, finds happiness”. His son, Rabbi Isaac, questioned him about this, to which Rav Yehudah said that although Isaac’s mother “was indeed irascible, she could be easily appeased with a kindly word.”

Judging the Self

The Hebrew word for prayer l’hitpalel, literally means “to judge one’s self”. Prayer has a much deeper purpose: it is a time to meditate on one’s inner qualities, both positive and negative, and to do what’s sometimes called a cheshbon nefesh, an “accounting of the soul”. Prayer is meant to be an experience of self-discovery. A person should not just ask things of God, but question why they are asking this of God. Do you really need even more money? What would you do with it? Might it actually have negative consequences rather than positive ones? Would you spend it on another nice car, or donate it to a good cause? Why do you need good health? To have the strength for ever more sins, or so that you can fulfill more mitzvot? Do you want children for your own selfish reasons or, like Hannah, to raise tzadikim that will rectify the world and infuse it with more light and holiness?

Prayer is not simply for stating our requests, but analyzing and understanding them. Through proper prayer, we might come to the conclusion that our requests need to be modified, or sometimes annulled entirely. And when finally making a request, it is important to explain clearly why you need that particular thing, and what good will come out of it.

Central to this entire process is personal growth and self-development. In that meditative state, a person should be able to dig deep into their psyche, find their deepest flaws, and resolve to repair them. In the merit of this, God may grant the person’s request. To paraphrase our Sages (Avot 2:4), when we align our will with God’s will, then our wishes become one with His wishes, and our prayers are immediately fulfilled.

Once more, the same is true in marriage. Each partner must constantly judge their performance, and measure how good of a spouse they have been. What am I doing right and what am I doing wrong? Where can I improve? How can I make my spouse’s life easier today? Where can I be more supportive? What exactly do I need from my spouse and why? In the same way that we are meant to align our will with God’s will, we must also align our will with that of our spouse.

The Torah commands that a husband and wife must “cleave unto each other and become one flesh” (Genesis 2:24). The two halves of this one soul must reunite completely. This is what Isaac and Rebecca did, so much so that they even prayed as one. In fact, Isaac and Rebecca were the first to perfectly fulfil God’s command of becoming one, and this is hinted to in the fact that the gematria of “Isaac” (יצחק) and “Rebecca” (רבקה) is 515, equal to “one flesh” (בשר אחד). More amazing still, 515 is also the value of “prayer” (תפלה). The Torah itself makes it clear that marital union and prayer are intertwined.

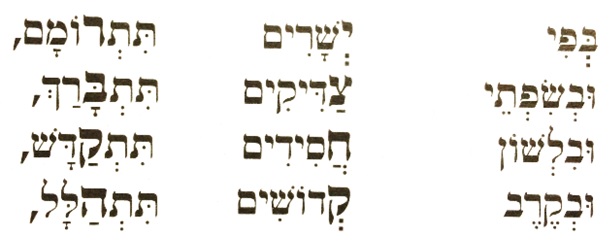

One of the most popular Jewish prayers is “Nishmat Kol Chai”, recited each Shabbat right before the Shema and Amidah. The prayer ends with an acrostic that has the names of Isaac and Rebecca. The names are highlighted to remind us of proper prayer, and that first loving couple which personified it.

Confession

The last major aspect of Jewish prayer is confession. Following the verses of praise and the requests comes vidui, confessing one’s sins and genuinely regretting them. It is important to be honest with ourselves and admit when we are wrong. Among other things, this further instills within us a sense of humility. The Talmud (Sotah 5a) states with regards to a person who has an ego that God declares: “I and he cannot both dwell in the world.” God’s presence cannot be found around a proud person.

In marriage, too, ego has no place. It is of utmost significance to be honest and admit when we make mistakes. It is sometimes said that the three hardest words to utter are “I love you” and “I am sorry”. No matter how hard it might be, these words need to be a regular part of a healthy marriage’s vocabulary.

And more than just saying sorry, confession means being totally open in the relationship. There should not be secrets or surprises. As we say in our prayers, God examines the inner recesses of our hearts, and a couple must likewise know each other’s deepest crevices, for this is what it means to be one. In place of surreptitiousness and cryptic language, there must be a clear channel of communication that is always wide open and free of obstructions.

To summarize, successful prayer requires first and foremost a great deal of positive, praising, grateful language, as does any marriage. Prayer also requires, like marriage, a tremendous amount of self-analysis, self-discovery, and growth. And finally, both prayer and marriage require unfailing honesty, open communication, and forgiveness. In prayer, we make God the centre of our universe. In marriage we make our spouse the centre of our universe. In both, the result is that we ultimately become the centre of their universe, and thus we become, truly, one.