In this week’s parasha, Lech Lecha, we read of God’s covenant with Abraham, which was sealed with a circumcision. For centuries, the most important honour given at a traditional brit milah is the role of sandak, or sandek, the person who holds the child during the circumcision. While everyone knows what a sandak is, few actually know what a sandak is! Where did this role come from? What does it mean? And what is the deeper spiritual significance behind it?

The Godfather

The role of the sandak emerged from the necessity of the mohel having an assistant. Someone, of course, has to hold the baby and keep the legs away so that the mohel can properly do his job. This is actually the simplest meaning of the term “sandak” which, like many Jewish words, has its origins in a Greek etymology: sunteknos, or syntekno, literally meaning the person “with the child” or the “child’s companion”. In Latin, which was also familiar to our ancient Sages, there is a related etymology that comes of the Greek, but has a further meaning:

The Latin term syndic referred to a government official or representative, especially a judge. It comes from the earlier Greek root sundike, literally meaning the person tasked “with justice”. Such a person would have been granted a measure of power by the state, and could confer protection to others (or at least advocate on behalf of others). The same term is the root of the modern word “syndicate”, referring to a group that comes together to make themselves more powerful in order to accomplish some goal (often of a criminal nature, but not necessarily).

The Latin syndic is the most direct etymology for the term sandak, and implies that the sandak has the job of protecting the child. For this reason, the sandak is often referred to as the Jewish version of a “godfather”. In fact, in olden times another term for sandak was av sheni, the “second father”. It is possible that it came with the responsibility to care for the child in the event that the father passed away. This is why some say that the father of the child should not be the sandak for his own baby.

Others say that the father should be the sandak, for the role is only of a spiritual nature, and there is no other obligation of the sandak after the brit. Mystical texts speak of a spiritual danger to the uncircumcised child, which is why there are customs to stay up all night before the brit to learn Torah in order to confer spiritual protection to the child (called a Brit Itzchak or a Vach Nacht). From this perspective, there is no reason why a father cannot be the sandak for his own child. Moreover, the mitzvah of circumcision is actually incumbent upon the father himself. Ideally, the father should circumcise his own child, and only if he is unable to should he appoint a professional mohel to serve in his stead. Therefore, by being the sandak, the father can at least participate directly in the mitzvah in an alternate way.

It is fitting to point out here a possible Jewish origin for the term “godfather”. It may come from a Midrash on this week’s parasha. The Sages ask: who was Abraham’s sandak when he was circumcised? They answer that God Himself was the sandak for Abraham. He was, quite literally, his “Godfather”.

Enter Eliyahu

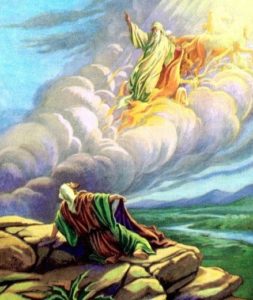

Another mystery of the brit milah ceremony is the “Chair of Eliyahu”. Every brit has a special chair designated for the prophet-angel Eliyahu, and it is customary for the sandak to sit on this chair, upon which the circumcision takes place. The chair is there because it is said that Eliyahu attends every brit. Why? As we’ve written in the past, Eliyahu once accused the Jewish people of abandoning God’s covenant (I Kings 19:10), God replied:

I vow that whenever My children make this sign in their flesh, you will be present, and the mouth which testified that the Jewish people have abandoned My covenant will testify that they are keeping it. (Zohar I, 93a)

In a slightly different version, the Midrash (Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer, 29) records that Eliyahu praised himself by saying that he has always been “zealous” for God and His covenant. And yet, Eliyahu fled from the evil Queen Jezebel when she was out to get him for trying to get the Jews to return to the Covenant. Because he fled and abandoned his own mission, God tasked him with being present at each brit milah, every time a new Jew is brought into the Covenant. The Midrash concludes that this is why we place a chair for Eliyahu at each brit.

We’ve noted multiple times before that Eliyahu never died and was taken up to Heaven alive, being transformed into an angel, called “Sandalfon”. As explained here, Sandalfon is also a Greek-derived appellation that the Sages used, to avoid using the true angelic name which is a secret. It isn’t difficult to see that the root of Sandalfon is the same as the root of sandak. And we can now understand why the sandak sits on Eliyahu’s chair:

The sandak serves as the earthly representative of Eliyahu. He is imbued with the spirit of that angel-prophet, and this is how Eliyahu is able to “attend” every brit milah, as God instructed him. It isn’t just a metaphorical thing, the sandak is really elevated to a higher angelic status. This is why it is customary (especially in Sephardic communities) for people to request a blessing from the sandak after the brit. The sandak carries this great blessing with him all day. For example, if the sandak later goes to pray Minchah at a minyan—even one that had nothing to do with the brit, and could be in a difficult country altogether!—that minyan does not pray Tachanun, the “sad” part of the prayer service. The presence of the sandak changes everything around him. He is likened to a walking, real-life angel. In fact, Jewish tradition holds that a sandak has all of his sins erased, and is then blessed with tremendous abundance.

For this reason, there is a rabbinic debate whether a single individual should be a sandak more than once. Because it is such a great honour, and carries such intense spiritual potential, some hold that we should spread the opportunity to as many different people as possible. Others maintain that there is no requirement to do so, and it is best to select the most righteous individual to serve as sandak. Because the sandak is the spiritual “companion” of the child, it is believed that some of the sandak’s own qualities will pass on to that child. It is therefore best to choose a righteous person. (In certain communities it was once normal for the local rabbi to be the sandak for all the children. Also, among those rabbinic authorities who do permit a person being sandak multiple times, some say a person should still not be sandak multiple times within a single family.)

Another custom, still strong today, is to honour a grandfather with being sandak. Rabbi Aryeh Lebowitz points out how this may come from the Torah itself, where we read: “And Joseph saw Ephraim’s children of the third generation; the children also of Machir the son of Menashe were born upon Joseph’s knees.” (Genesis 50:23) The Targum Yonatan explains that Joseph was the sandak for his grandsons.

On a final interesting note, there is a question regarding selecting a sandak who, while righteous, might have some kind of deficiency or a physical disability. The Lubavitcher Rebbe once responded to a question where a person asked if it is okay that the sandak is infertile. The Rebbe replied in the affirmative, saying that only the positive qualities of the sandak are passed on to the child. This makes perfect sense in light of the fact that any negative qualities of the sandak are erased that day, as noted, and he is elevated to the status of a wholesome angel that has no deficiencies.

Pingback: Pinchas is Eliyahu—and So Much More | Mayim Achronim