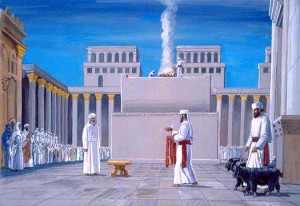

The parashot of Acharei Mot and Kedoshim are typically read together. The major part of Acharei deals with various sacrificial services, most notably those concerning Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. Kedoshim begins by telling us that it is every person’s mission in life to become holy, just as God Himself is holy. This parasha is concerned with ethics, morality, and the path to righteousness, and includes the famous dictum to “Love your fellow as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18).

Perhaps the most peculiar item in this week’s portion is the mention of Azazel. As part of the atonement procedure on Yom Kippur, God commands Aaron to select (through a random lottery) two goats: one to be sacrificed, and another to be sent “to Azazel, in the wilderness” (Lev. 16:10). Aaron would place his hands on the goat to Azazel, and confess all of the people’s sins, as if transferring them to the animal (v. 21). The goat was then sent off into the wilderness.

The Rambam (Moreh Nevuchim, Part III, Ch. 46) writes that this act is completely symbolic. It does not mean that the High Priest literally transferred the people’s sins onto the goat, but that witnessing this act was meant to inspire a sense of repentance in the people, “as if to say, we have freed ourselves of our previous deeds, have cast them behind our backs, and removed them from us as far as possible.”

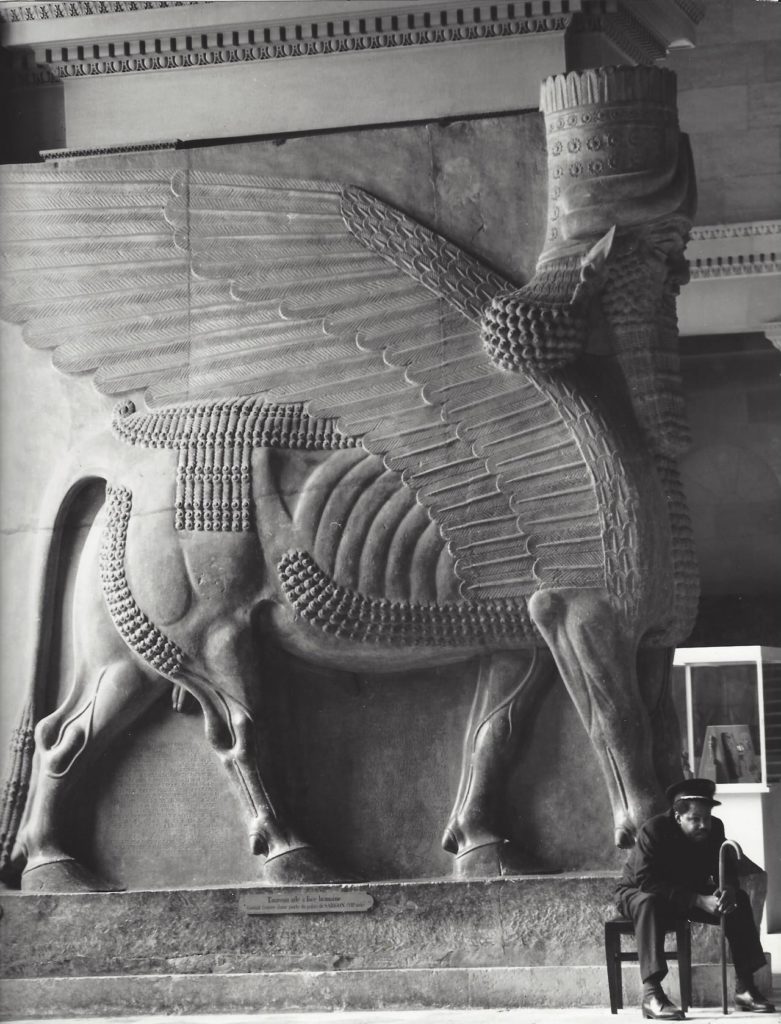

But what exactly is “Azazel”? What does the word mean? And why was the goat that symbolized sin sent towards it? The Talmud (Yoma 67b) maintains that the word Azazel can be broken down to mean “hardest of mountains”. This may be why some believe that the goat was sent off the edge of a mountainous cliff down to its death. The Talmud then presents the opinion of the school of Rabbi Ishmael: Azazel is a contraction of two names: Aza (or Uza) and Aza’el, and the goat atones for their sins. Other than this short allusion, this page of Talmud says nothing more.

Who were Aza and Aza’el?

The Fallen Angels

The origins of Aza and Aza’el are described in the Midrash (Yalkut Shimoni, Beresheet 44). When speaking of midrashic literature, it is important to remember the old adage that goes something like: one who believes that midrash is not true is a heretic, but one who believes that midrash is literally true is a fool. After all, the midrash corresponds to the third level of Torah study, referring to the metaphorical and allegorical level. (The other levels are peshat, the literal meaning; remez, the sub-textual meaning; and sod, esoteric/metaphysical secrets.)

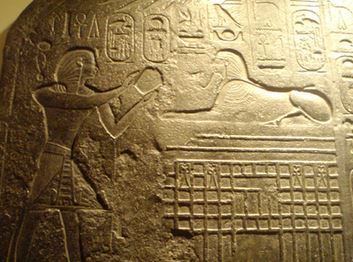

Aza’el and Aza (also known as Shemhazai) were angels who saw the terrible sins of the people in the pre-Flood generation and scoffed at the pathetic humans. God told them that if they had been on Earth and given free will, they would succumb to their evil inclination far worse than people do. The angels wanted to prove God wrong, and asked Him to send them down to Earth into a physical body. God complied, and just as He had said, the angels quickly fell into all forms of evil.

Firstly, they could not hold back from the beautiful women, and this is what Genesis 6:2 means when it refers to divine beings mating with humans. The Midrash continues to say that it was these angels that taught women the art of makeup and provocative dress in order to entice men into further sin. These angels helped to bring the sword to the world, increasing bloodshed and warfare, as well as the consumption of animal meat, which was at this point forbidden, as God had only permitted Adam and Eve to consume fruits and vegetables.

Ultimately, the Midrash tells us that Shemhazai recognized his evil ways, and began a long process of repentance. No longer on Earth, but still not welcome back in the Heavenly realms, Shemhazai was suspended between the two worlds. Aza’el, on the other hand, refused to repent, and continued his evil ways. Thus, the Midrash concludes that the High Priest, in an act of repentance, would symbolically send the people’s sins towards Azazel, the one who taught mankind a new level of sinfulness, and refused to repent.

More details can be found in the Apocrypha. The Apocrypha refers to various ancient books which were not officially included in the Tanakh. Their origins are unclear, as is their authenticity. Nonetheless, they appear to have been well-known among the Jewish Sages, and are referenced in Talmud, Midrash, and Kabbalistic writings. One of the most famous of the apocryphal books is the Book of Enoch, which describes the journeys of Enoch (Hanoch, in Hebrew), who is briefly mentioned in Genesis 5:22. In the Book of Enoch, it is recorded that God sent the angel Raphael to apprehend Aza’el and stop his evil ways. Aza’el was chained to the “hardest of mountains” in the wilderness, as the Talmud quoted above explained. His painful imprisonment was a punishment, and the goats sent his way were a form of atonement for his sins. It is written there that at the End of Days, his time will come to an end, and Aza’el will finally be gone for good.

The above article is an excerpt from Garments of Light: 70 Illuminating Essays on the Weekly Torah Portion and Holidays. Click here to get the book!