This week’s parasha, Vayeshev, relays the infamous story of the Sale of Joseph. As explored in the past, a careful reading of the text shows that Joseph’s brothers didn’t necessarily sell him (see ‘Was Joseph Really Sold by His Brothers?’ in Garments of Light, Volume One). They threw him in a pit and abandoned him. They then discussed what to do next, and Yehudah only suggested selling him. While they were still deliberating, Reuben goes to get Joseph from the pit and discovers that he is no longer there. Midianites had found Joseph and enslaved him, then sold him to Ishmaelites that took him down to Egypt. Reuben runs to his brothers to relay that Joseph is gone! (Genesis 37:29-30)

The plain reading of the text suggests the brothers did not sell Joseph. However, because they abandoned him and seriously considered selling him, they took on the blame for it anyway. Most commentaries, including Rashi, insist that the brothers really were directly involved in the sale, but some commentators argue otherwise, including Rashi’s grandson Rashbam (Rabbi Shmuel ben Meir, c. 1085-1158), who wrote:

… עברו אנשים מדיינים אחרים דרך שם, וראוהו בבור ומשכוהו ומכרוהו המדיינים לישמעאלים. ויש לומר שהאחים לא ידעו, ואף על פי אשר כתב: אשר מכרתם אותי מצרימה (בראשית מ”ה:ד’), יש לומר: שהגרמת מעשיהם סייעה במכירתו. זה נראה לי לפי עומק דרך פשוטו של מקרא. כי ויעברו אנשים מדיינים – משמע על ידי מקרה, והם מכרוהו לישמעאלים.

… other, Midianite people passed by there and saw [Joseph] in the pit and pulled him out and sold him to the Ishmaelites. One could say that the brothers did not know of this, even though it is later written “that you sold me to Egypt” (Genesis 45:4) this is to mean that their actions indirectly caused his sale. This appears to me to be the more profound simple understanding of the verses, for “Midianite people passed by” coincidentally at that time, and they sold him to the Ishmaelites.

This interpretation would explain many other details, for instance, why were the brothers so shocked to see Joseph years later in Egypt? If they had sold him to a slave caravan going down to Egypt, why would they be surprised to find him there? They should have known he is in Egypt! In fact, we know the brothers all repented wholeheartedly, so why did they not, at some point, go down to Egypt and look for him or try to bring him back? The evidence is quite strong that the brothers genuinely did not know where he was.

A related follow-up question: Which brothers were there when Joseph was sold to begin with? The parasha begins by telling us that Joseph “tended the flocks with his brothers, and he was a youth with the sons of his father’s wives Bilhah and Zilpah.” (Genesis 37:2) It seems Joseph spent most of his time with the four sons from the concubine-wives, ie. Dan, Naftali, Gad, and Asher—the younger siblings. The sons of Leah, meanwhile, kept to themselves, perhaps because of seniority or maybe even an air of superiority. It seems to be that Joseph and the four sons of the concubine wives stayed close to home and shepherded their flocks near Jacob’s tent, while the sons of Leah were shepherding further away near Shechem and Dotan, which is why Jacob sends Joseph on a mission to find them and see what they are up to (Genesis 37:14). Note how the only brothers that are named in the account surrounding the sale are Reuben, Shimon, and Judah—three of the six sons of Leah. None of the other brothers are mentioned. One could make the case that maybe only the sons of Leah were involved.

The Sefirot of Mochin above (in blue) and the Sefirot of the Middot below (in red) on the mystical “Tree of Life”.

Kabbalistically, the children of Leah make up a complete set corresponding to the lower Sefirot. Recall that the Ten Sefirot are divided up into the three lofty Mochin (“intellectual” faculties) and the seven lower Middot (“emotional” faculties). The firstborn Reuben, the kind one who tried to save Joseph, is Chessed, the first of the Middot. Chessed is associated with water, and Jacob later describes Reuben as pachaz k’mayim, “impetuous like water”. Second-born Shimon, the strongest, feistiest, and most judgemental of the brothers, neatly corresponds to second Gevurah, or Din, “severity” and “judgement”. The priestly Levi is Tiferet, the repentant Yehudah is Netzach, and Issachar and Zevulun are Hod and Yesod. Their sister Dinah, of course, corresponds to the feminine Malkhut.

It appears from the plain text of the parasha that the children of Leah mostly kept to their own “Sefirotic” group. That said, we find that Reuben was not with them when they discussed the sale of Joseph. The Zohar (I, 185b) explains that the sons of Jacob took turns tending to their father’s needs. That day was the day that Reuben was responsible for Jacob, so he was away with his father. This explains why Reuben only reappears later in the narrative. He only rushed back, the Zohar says, to save Joseph from the pit, and was completely unaware of the sale (וְאֲפִילּוּ רְאוּבֵן לָא יָדַע מֵהַהוּא זְבִינָא דְיוֹסֵף). He would not find out until many years later in Egypt. If we put all of this information together, it appears only five of the brothers were directly involved: Shimon, Levi, Yehudah, Issachar, and Zevulun.* All ten are ultimately held culpable because brothers are all responsible for each other, and should always be aware of each other’s whereabouts and wellbeing. The fact that they let Joseph get sold into slavery was an absolute failure on the part of all ten, even those who were not technically involved. And that’s why we have so many traditions and teachings about the need for all ten brothers to be rectified, including through the Ten Martyrs later in history (see ‘The Ten Martyrs & the Message of Yom Kippur’ in Garments of Light, Volume Two).

But what of the five brothers that were mainly culpable? They would certainly need a special, additional tikkun. As we look through Jewish history, we find several more groups of “five brothers” that are of tremendous significance. Each of these groups of five propel Judaism forward and usher in a new era in Jewish history. Who are these groups of five and how do they relate to the five brothers of Joseph?

The Maccabees & the Tannaim

We find a set of five brothers with similar names to the first set in the story of Chanukah. Parashat Vayeshev is always read right around Chanukah time, and there are no coincidences in the Jewish calendar! Could it be that the righteous Yehudah, who takes the lead among the sons of Jacob and takes the lead in repentance, returns as Yehudah Maccabee, who takes the lead among the sons of Matityahu and takes the lead to save Judaism in the Second Temple era? Shimon, who was the most culpable of the sons and was not even blessed by Jacob on his deathbed (Genesis 49), returns as Simon Thassi, “Shimon the Righteous”, the last surviving son of the Maccabees and arguably the first rabbi. What a tikkun that would make! Levi, the family priest in Jacob’s time, returns as Elazar, described as the most “religious” of the Maccabees, the one tasked with learning and praying while the other brothers fought the Seleucids (see II Maccabees 8:22-23). Elazar eventually joins the battle himself, and tragically gets trampled by a war elephant. The little-known Issachar and Zevulun, who are not mentioned in the Genesis account, parallel Yonatan and Yochanan, of whom we also know the least about when it comes to the Maccabees.

In fact, as explored in the past, it is possible that these same five souls return once again in the students of Rabbi Akiva: Yehuda bar Ilai, Shimon bar Yochai, Elazar ben Shammua, Yose bar Halafta, and Meir. These five rabbis were involved in a great war, too—the Bar Kochva Revolt—and were among the few survivors. The Talmud credits them with reviving Judaism after the devastation of the war (Yevamot 62b). Again, this would serve as a worthy tikkun for the five sons of Jacob and the failure with Joseph. The fact that the five rabbis were students of Akiva (Aramaic for “Yakov”) bar Yosef might further hint to a connection to Joseph in the Torah.

With the first five brothers, Joseph told them that they intended something negative, but it was all in Hashem’s hands and He orchestrated it all to bring about something positive. It was all meant to happen, to bring Israel to its next phase of development in Egypt, and to set the stage for the Exodus. The same was true the second time around during Chanukah, with the five sons of Matityahu saving Judaism and bringing it to its next stage of development, the rabbinic era. And the third time was with the students of Rabbi Akiva, who were once again able to preserve Judaism amidst intense Roman persecution and exile, and adapt Judaism to a reality without a Temple, while laying the foundations of the Mishnah and Talmud.

The Rothschilds & the Chanukah Lights

One might go even further and find another set of five Jewish brothers who make a massive impact not only on the course of the Jewish people but on the world at large: the five original Rothschild sons. Their father Mayer Rothschild was initially set to become a rabbi. In his youth, he apprenticed with a banker and eventually became one himself. He was a deeply religious man, and ensured his five sons were the same. None of them intermarried or converted out. (Eldest son Amschel was particularly known to be very religious, and was nicknamed “the pious Rothschild”. Grandson Lionel was the first Jew in British parliament, and was sworn in over a Tanakh, wearing a kippah.)

The Rothschilds invested huge sums in support of shuls, yeshivas, orphanages, and Jewish institutions, and later played a big role in the Zionist movement and establishing some of the first Jewish towns in Israel. (A famous Hasidic story attributes Rothschild wealth and success to a blessing from Rabbi Hershelle Tschortkower.) Grandson Edmond de Rothschild gave the funds to establish Rishon Lezion, Metulla, Ekron, Rosh Pina, and Zichron Yaakov (named after his father Jacob Rothschild). He purchased an additional 125,000 acres of land in Israel, and gave the equivalent of what is today $700 million for the early infrastructure that made Israel possible. He was beloved by Jews and Arabs alike, and was called haNadiv haYadua, “the Famous Benefactor”.

Edmond de Rothschild on an Israeli 500 Shekel Note (1982)

The name “Rothschild”, literally red shield, comes from the red banner the family had above their door in the Jewish quarter of Frankfurt. The family later designed a coat of arms that included a red shield, and an arm holding five arrows to represent the five brothers, based on Psalms 127:4, “Like arrows in the hand of a warrior are sons born to a man in his youth.” Some conspiracy theorists have argued that the red shield is symbolic of the family secretly being Edomites, connected to the wicked Esau. However, one could make the opposite case: the Rothschilds probably did more than any other family at the time to shield the Jewish people from the oppression of Edom! They also invested heavily in Edom, paying for some of the first European rail networks and modern factories, as well as hospitals, universities and research labs, museums, charities, and large public works.

The name “Rothschild”, literally red shield, comes from the red banner the family had above their door in the Jewish quarter of Frankfurt. The family later designed a coat of arms that included a red shield, and an arm holding five arrows to represent the five brothers, based on Psalms 127:4, “Like arrows in the hand of a warrior are sons born to a man in his youth.” Some conspiracy theorists have argued that the red shield is symbolic of the family secretly being Edomites, connected to the wicked Esau. However, one could make the opposite case: the Rothschilds probably did more than any other family at the time to shield the Jewish people from the oppression of Edom! They also invested heavily in Edom, paying for some of the first European rail networks and modern factories, as well as hospitals, universities and research labs, museums, charities, and large public works.

We find a great deal of similarity between the five Maccabee sons and the five Rothschild sons. In both cases, the sons were deeply religious, their children less so, and the descendants that followed leaving the faith entirely. The Hasmonean dynasty of the Maccabees soon became entirely Hellenistic, taking on Greek names (like Alexander Yannai and Yochanan Hyrcanus) and Greek titles (like strategos and basileus), and eventually even persecuting rabbis, causing sages like Shimon ben Shatach and Yehoshua ben Perachia to flee to Egypt. Among the Rothschilds, too, within a few generations there was widespread assimilation, intermarriage, conversions, and support for all kinds of things antithetical to Judaism. Some Rothschilds even became vocal anti-Zionists and refused to ever visit Israel.

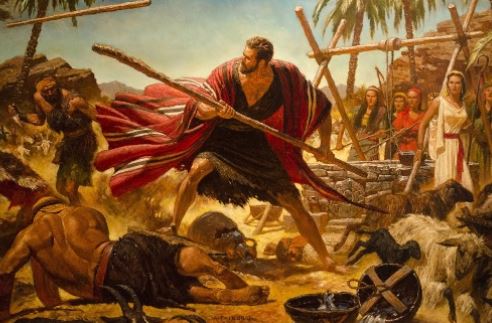

‘Joseph Makes Himself Known to His Brethren’ by Gustav Doré

And it all ties back to Joseph in Egypt. In fact, some see Joseph as a spiritual precursor to the Rothschilds: a “Court Jew” who became incredibly wealthy and powerful, drawing the ire and resentment of the Egyptians. The result is ultimately more antisemitism and persecution of Jews, but that leads to an Exodus to the Promised Land. This is, of course, reminiscent of what we witnessed in the 20th Century. It all reminds us of Joseph’s own words: “Now, do not be distressed or reproach yourselves because you sold me here; it was to save life that God sent me ahead of you… God has sent me ahead of you to ensure your survival on earth, and to save your lives in an extraordinary deliverance. So, it was not you who sent me here, but God…” (Genesis 45:4-8) We must remember that all is in Hashem’s hands. He orchestrates every detail of history. Moments that initially appear negative end up being revealed as positive in the long run. And this was Joseph’s superpower: having an ayin tova, a good eye, and seeing the positive within all things. That is why Jacob described him as being ben porat Yosef, ben porat alei ayin, good upon the eye (Genesis 49:22).

The Chanukah lights have the same message. They represent the ohr haganuz, the hidden light of Creation. We are not supposed to derive physical benefit from the Chanukah lights (hence the shamash) to remember to gaze beyond the physical light and into the spiritual. They remind us that things are not always as they appear to be. There is a hidden light beneath the revealed one. Sometimes we just need to look a little deeper to uncover it.

Happy Chanukah!

*There is further support for this hypothesis later in the Torah, in parashat Vayigash. When Jacob is reunited with Joseph and the whole family immigrates to Egypt, we read how Joseph wanted to introduce his brothers to Pharaoh. Strangely, he does not present all of his brothers, but instead he “selected five of his brothers to present before Pharaoh.” (Genesis 47:2) Why did he only select five of them? Perhaps these were the very same five that he last remembered throwing him into the pit! Maybe the tikkun here was in having to experience the stress of meeting the Pharaoh, and diminishing themselves before him, describing themselves as his “servants”, and pleading to allow them to live in Egypt (47:4). No doubt, a very humbling experience for the five.