This week’s parasha, the second last of the Torah, is Ha’azinu. This parasha is unique in that it consists almost entirely of one lengthy song – clearly visible when looking at a Torah scroll, where the text of Ha’azinu is split into two narrow columns. Moses sang this prophetic song to the nation right before his passing.

Two columns of parashat Ha’azinu

In the verses that introduce it (Deut. 31:19), we see God commanding Moses to write the song and “teach it to the Children of Israel. Place it in their mouths so that this song will be for Me a witness for the Children of Israel.” God wanted Moses to diligently teach this song to the entire nation. In fact, the actual wording of the verse has God commanding everyone – each member of the nation – to write the song for themselves. It is based on this verse that the Sages drew the mitzvah of writing a Torah scroll (or participating in writing one), even though the plain text of the verse states only to write this particular song, Ha’azinu.

Perhaps because of this, the Ramban taught that Ha’azinu contains the entire Torah within it. Moreover, he believed that every detail of every person’s life is somehow encoded within this song! In one famous story, when a student of the Ramban, a man named Avner, heard this teaching, he was so baffled by it that he left Judaism entirely, converted to another religion, and became a prominent anti-Semite. When Avner later confronted the Ramban, the Rabbi showed him how one verse in the song did indeed accurately point to this man’s life. Avner was so ashamed that he disappeared, never to be heard from again.

Heavenly Princes

And so, each and every one of the song’s 43 verses has a great deal to teach us. The eighth verse begins by telling us that God gave each nation their lot, and the ninth verse says that “Hashem’s portion is His people, the lot of His inheritance.” The Zohar comments on these words that while God established Heavenly “princes” to watch over every nation in the world, Israel is watched over by God Himself. The Ramban (in his Discourse on Rosh Hashanah) elaborates:

He gave each and every nation… some known star or constellation, as is known by means of the science of astrology… Higher above [the constellations] are the angels of the Supreme One, whom He appointed as “princes” over them… It is further written, “So shall you be My people, and I will be your God, and you will not be subject to other powers at all.” (Jeremiah 11:4)

When we often say that Hashem is our God (as we do in the daily Shema), or when the Tanakh writes that we are God’s people, this does not mean that gentiles cannot have a relationship with God, or that there are other gods out there for the non-Jewish world. Rather, it means that while God oversees absolutely everything in His universe, and has created all people, He has also appointed various Heavenly (or astrological) forces above each nation – except Israel. These forces are not independent in their own right, as they are subject to the angels above them, and these angels ultimately serve God. As such, the nations of the world have various Heavenly intermediaries between themselves and Hashem. Israel, however, has a direct connection to Him. In fact, this is the hidden meaning within the name “Israel” (ישראל), which can be read as yashar El. (ישר-אל), “straight to God”.

Ain Mazal L’Israel

Long before the Ramban, the Sages of the Talmud debated whether the constellations had an effect on people (Shabbat 156a). The consensus of the Rabbis was that constellations do impact people, but Jews are free from this influence. They learn this from the prophet Jeremiah, who prophesied: “Thus said Hashem: Learn not the way of the nations, and be not dismayed at the signs of heaven, for the nations are dismayed at them.” (10:2) God tells Israel not to draw meaning from heavenly signs as the other nations do. The Talmud goes on to tell us a story about Abraham, who cried out to God: “Master of the Universe! I have looked at the constellations and find that I am not fated to have children.” To this, God replied: “Stop your star-gazing! Israel has no constellations.”

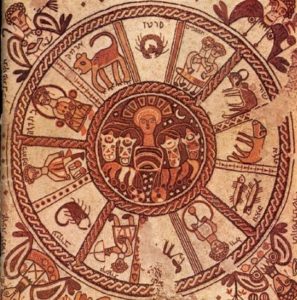

Hebrew Zodiac from a 6th-Century Synagogue

Elsewhere, the Talmud tells us that Abraham was once a powerful astrologer, and great men from around the world came to consult with him about their fortunes (Bava Batra 16b). When Abraham looked into his own fate, he saw that he would not have children. God commanded him to desist from astrology, for the Jewish people have the power to transcend the stars. Of course, Abraham went on to have many children.

Later on, Moses would record in the Torah the prohibition for Jews to consult various fortune-tellers and astrologers. The Rambam codifies the law in this way:

It is forbidden to tell fortunes. [This applies] even though one does not perform a deed, but merely relates the falsehoods which the fools consider to be words of truth and wisdom. Anyone who performs a deed because of an astrological calculation or arranges his work or his journeys to fit a time that was suggested by the astrologers is [liable for] lashes, as [Leviticus 19:26] states: “Do not tell fortunes.”

(Sefer HaMadda, Hilchot Avodah Zarah, Chapter 11, Halacha 9)

Transcending Nature

We see from the above that various Heavenly forces, angels, and constellations do exist, and certainly do influence the world. Astrological signs can be potent forces. Ironically, earlier in his discourse, the Ramban points out how astrology is intricately tied into the Jewish calendar: it is no coincidence that Pesach is celebrated in the month of Nisan, the sign of which is Aries (the ram, or sheep), since the main mitzvah of Pesach was to sacrifice a lamb; and it is no coincidence that Rosh Hashanah – judgement day, when each person is put on trial – is in the month of Tishrei, the sign of which is Libra, the scales of justice. The Midrash (Yalkut Shimoni, Shemot 418) even tells us how each of the 12 Tribes of Israel corresponds to one of the 12 astrological signs of the zodiac!

And yet, all the sources are clear: Jews are not to dabble in astrology, for we have no need for intermediaries, and we have all the power to break free from the influence of the constellations. It is precisely when we believe in astrology that it becomes real, just as Abraham had no children as long as he believed in the heavenly signs that he saw. Every Jew must realize that we are Israel, yashar El, and that Hashem alone is our astrological sign. There is no need to believe in what the Rambam calls “emptiness and vanity”. The Rambam ends his laws on this subject by telling us to live up to the Torah’s call (Deut. 18:13) to be of “perfect faith with Hashem, your God.” When one has perfect faith in the Master of the Universe, anything is possible, and this is how God finished his rebuke to Abraham:

“Stop your star-gazing! Ain mazal l’Israel. What is your calculation? Is it because Jupiter stands in the West? Then I will turn it back and place it in the East!”

The article above is an excerpt from Garments of Light: 70 Illuminating Essays on the Weekly Torah Portion and Holidays. Click here to get the book!