This Saturday is Shabbat HaGadol, the “Great Sabbath” before Pesach. One of the big mysteries surrounding the holiday is the origin of this term. Why is the Shabbat preceding Pesach described as being gadol? Why aren’t the Sabbaths before other big holidays described the same way? What makes this Shabbat so special? Over the centuries, many different explanations have been given.

Perhaps the most famous explanation is that on the Shabbat before the Exodus, the Egyptians got word of the impending Tenth Plague and Death of the Firstborn so, naturally, all the Egyptian firstborn rose up in protest. They revolted against Pharaoh and pressured him to free the Israelites so that their lives would be spared. A civil war ensued and many Egyptians were struck down. This is why we read in Psalms (136:10) that God “struck down the Egyptians through their firstborn”. The verse can be read to mean that God struck down the Egyptian firstborn, or that He struck down the Egyptians at the hands of their own firstborn! This great civil war (a mini-plague in its own right) gave Shabbat HaGadol its name.

Khnum

Another explanation is that on (or just prior to) the Sabbath before the Exodus the Israelites had been commanded to prepare the sheep for the paschal sacrifice. Since this was in the month of Nisan, the astrological sign for which is a sheep or ram, the Egyptians were in the midst of worshipping their ram-headed sheep god Khnum. To the Egyptians, the sacrifice of a sheep at that time would have been appalling and sacrilegious. Yet, in great dread of the Israelites and their God, the Egyptians stayed silent and did not protest what they knew was about to happen. This was a mini-miracle and yet another display of God’s greatness, hence Shabbat HaGadol.

A more pragmatic explanation for Shabbat HaGadol is that, since it is the Sabbath before Pesach, rabbis in all synagogues give an extra-long sermon in preparation for the holiday. There are a lot of halakhot to go over, and there is also a need for some words of inspiration. Because of the long speeches, it became known as Shabbat HaGadol. Finally, some hold that the name comes from the Haftarah typically read on the Shabbat before Pesach (Malachi 3), and its concluding prophesy about the return of Eliyahu before the “Great [Gadol] and Awesome Day of Hashem”. After all, we had finished last year’s seder by praying and hoping that next year we will be redeemed and in Jerusalem. So, the Shabbat right before the upcoming Pesach is our final wish that the Great Day of God will come now so that this year’s seder can be in Jerusalem as we hoped.

All of the above are wonderful explanations. I believe there might also be one more coming out of an oft-forgotten historical detail from the end of the Second Temple era.

The Great Calendar Debate

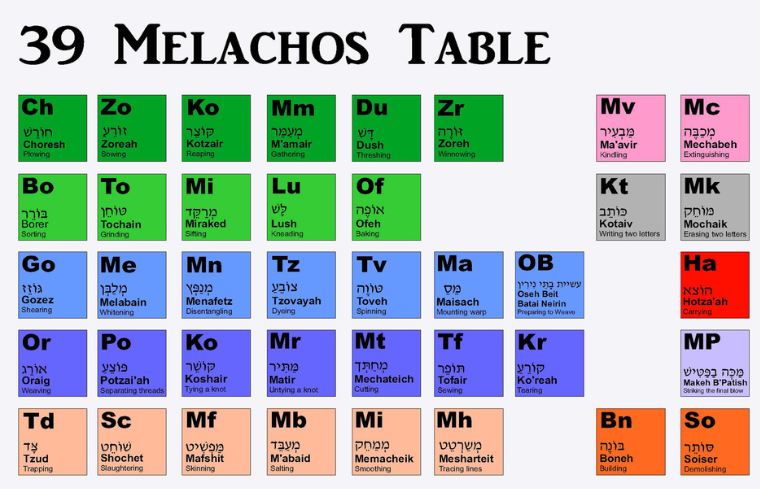

As is well-known, at the end of the Second Temple era Jewish life in the Holy Land was dominated by two major groups: the Perushim (“Pharisees”) and the Tzdukim (“Sadducees”). The latter held only to the strict observance of the Written Torah, with no particular reverence for oral tradition or oral law. For this reason, the Sadducees famously did not believe in an afterlife, since the Torah never explicitly mentions it, nor did they allow any use of an existing flame on Shabbat, based on their straight-forward reading of Exodus 35:3.

Another major debate between the Sadducees and Pharisees was regarding Sefirat haOmer. The Torah states that we must start counting the Omer from the day after the Sabbath (Leviticus 23:11, 15). The Sadducees took this literally, and began the Omer count from the day after the Shabbat of Pesach. This meant that they always began counting on Sunday and always celebrated Shavuot on Sunday. The Pharisees, meanwhile, based on oral tradition, held that the count must begin from the day after the first yom tov of Pesach, since the Torah often refers to holidays themselves as “Shabbats”, too. The count would always begin on the 16th of Nisan, making Shavuot always land around the 6th or 7th of Sivan (depending on lunar month lengths). The Pharisees insisted this was the correct way going back to Sinai, as taught by Moses.

Intriguingly, there was a third up-and-coming group of Jews at the time, the mysterious Essenes. They were originally a small break-away sect of Sadducees that also had beliefs similar to the Pharisees and did maintain certain binding oral traditions. The Essenes would have a large impact on the development of Rabbinic Judaism as we know it (which came mostly out of Pharisee Judaism) following the destruction of the Second Temple. Unlike the Pharisees and Sadducees, which held by a lunisolar calendar that used lunar months but aligned with solar years (as we still do today), the Essenes believed such a calendar was inaccurate and too flexible. They did not like it one bit that the lunar months were proclaimed by the Sanhedrin based on eyewitnesses who might be mistaken. Instead, the Essenes held only to a finely-tuned solar calendar which they thought was perfect.

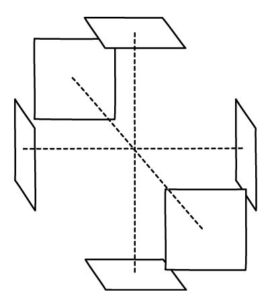

The Essene calendar (as described in the apocryphal but hugely important Book of Jubilees, ch. 6, among other sources) went as follows: There were 52 weeks divided up into 4 seasons, each with exactly 13 weeks totalling 91 days. The result was that holidays would always fall on the exact same weekday all the time. Shavuot was always celebrated on a Sunday, the 15th of Sivan. (They argued that Shavuot should be on a 15th just like the other regalim, Pesach and Sukkot.) The Essenes interpreted that verse in Leviticus to mean that the Omer count must start from the day after Shabbat after Pesach is over. So, the Essenes always celebrated Shavuot a week after the Sadducees! (Depending on when Pesach would fall in a given year, the Sadducees and Pharisees might celebrate Shavuot on the same day, or a day or two apart. In a year like this year, when Pesach falls on Shabbat, the Pharisees and Sadducees would have begun counting the Omer on the same Sunday and celebrated Shavuot on the same day.) The problem with the Essene calendar is that it had a year of 364 days, and it isn’t clear how they intercalated to stay aligned with the solar year of 365.24 days.

After the Temple was destroyed, Sadducee and Essene Judaism both disappeared (along with numerous other, smaller sects). Pharisee Judaism continued and evolved into “Rabbinic” Judaism. It was precisely the richness and fluidity of the oral tradition that allowed Judaism to survive and flourish. And we still have many remnants of our ancient Sages instituting practices partly to counter the mistaken Sadducee claims. Lighting Shabbat candles and eating warm chamin (like cholent) was a direct assault on Sadducee Judaism which kept the lights out and ate cold food to avoid making use of a flame. With this in mind, I believe we can posit another hypothesis for the origin of Shabbat HaGadol:

Unlike the Sadducees (and Essenes), our Sages held that the Omer count must start from the second day of Pesach since the first day of Pesach is itself like Shabbat. When the Torah says to count from the day after “Shabbat”, it means the day after the first yom tov of Pesach. In that case, if we insist on calling the first day of Pesach a Shabbat, what does that make the actual Shabbat preceding it? It’s like we have two Shabbats in a single week! So, perhaps it became customary to refer to the actual Shabbat as Shabbat haGadol, both to distinguish it from the Pesach mini-Shabbat and to emphasize the wrongness of the Sadducees and Essenes.

This leads us to an even bigger question: why did our Sages insist that Pesach is the Shabbat in question? Isn’t the Torah quite clear that the count should start from the Sabbath after Pesach? What is so important about tying Pesach to Shabbat?

Purpose of Creation

Rashi begins his commentary on the Torah by pointing out that Beresheet means that God created “for resheet”, and what is resheet? Proverbs 8:22 calls the Torah resheet darko, “the first of His way”, while Jeremiah 2:3 calls Israel resheet tevuato, “the first of His grain”. Therefore, God created the cosmos with the intention to eventually forge Israel and give His Torah. If not for this, He would have never created to begin with, as we read in Jeremiah 33:25-26 that “If not for My covenant day and night, I would have never established the laws of Heaven and Earth, so I will never reject the offspring of Jacob…”

The ‘Pillars of Creation’ in the Eagle Nebula (Courtesy: NASA)

Therefore, there is a deep, intrinsic connection between Creation and Pesach: Without a Genesis, there would be no Exodus, and without an Exodus God would have never bothered with a Genesis! This is why, when reciting Kiddush every Friday evening to welcome Shabbat, we say zekher l’yetziat Mitzrayim, “in memory of the Exodus from Egypt”. And it is why, when the Torah gives the Ten Commandments twice (in Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5), the first time it says Shabbat is in order to commemorate Genesis, while the second time it says Shabbat is in order to commemorate the Exodus! In the former, we are told to keep Shabbat because God rested on the Seventh Day of Creation, while in the latter we are told to keep Shabbat because we were once slaves working around the clock and we are no longer slaves so we should celebrate our freedom with a day of rest and divine service.

In short, Pesach and Shabbat are inseparable and represent two sides of the same coin. Our Sages insisted on commemorating Pesach itself as a Shabbat, for it cannot be any other way. Pesach is a Shabbat, the very reason for the existence not only of the Jewish people, but of the whole universe. And before the Pesach-Shabbat of Exodus comes the Great Shabbat of Genesis.

Shabbat Shalom!