Devarim, or Deuteronomy in English, is the fifth and final book of the Torah. Deuteronomy comes from the Greek deuteronomion, meaning “second law”, which itself comes from the alternate Hebrew name of the book, Mishneh Torah, meaning “repetition of the law”. The name stems from the fact that Deuteronomy is essentially a summary of the four previous books of the Torah. The key difference is that it is given in the point of view of Moses, and records his final sermon to the people before his death.

One of the enigmatic figures mentioned in this week’s parasha is Og, the king of the land of Bashan. This character is explicitly mentioned a total of 10 times in the Torah, of which 8 are in this portion alone. He is first mentioned in the introductory verses of the parasha (1:4), which state how Moses began his discourse after smiting Sihon, the king of the Amorites, and Og, the king of Bashan.

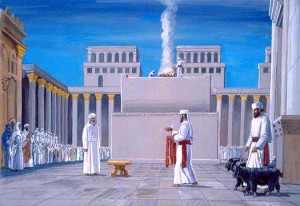

Og’s Bed, by Johann Balthasar Probst (1770)

We are later told how Og had come out to confront the children of Israel, and the Israelites defeated his army in battle. Og is said to be the last survivor of the Rephaim (3:11), which were apparently a nation of giants. His bed is described as being made of iron, and being nine cubits long, or roughly 18 feet!

Rashi provides a little more information. He tells us that Og was the last survivor of the Rephaim in the time of Abraham. It was then that the king Amraphel, together with his allies, dominated the Fertile Crescent region, and decimated many nations that inhabited it. One of these groups of victims were the Rephaim, and Og was the sole survivor among them. He was the “refugee” mentioned in Genesis 14:13 that came to Abraham to inform him of what had happened.

So, who was Og? Where did he come from? Why did he initially help Abraham, but then come out to battle Moses centuries later? And was he really a giant?

Half Man, Half Angel

The Talmud (Niddah 61a) tells us that Og was the grandson of Shemhazai. As we have written previously, Shemhazai was one of the two rebellious angels that had descended to Earth. These two angels argued before God that He should not have created man, who was so faulty and pathetic. God told the angels that had they been on Earth, and given the same challenges that man faced, they would be even worse.

The angels wanted to be tested anyway, and were thus brought down into Earthly bodies. Of course, just as God had said, they quickly fell into sin. This is what is meant by Genesis 6:2, which describes divine beings mating with human women. Their offspring, initially called Nephilim, were large and powerful, and were seen as “giants” by common people. However, during the Great Flood of Noah, all of these semi-angelic beings perished. Except for one.

The Sole Survivor

Midrashic texts famously record that Og was the only survivor of the Great Flood, aside from Noah and his family. When the torrential rains began, Og jumped onto the Ark and held on tightly (Zevachim 113b). He swore to Noah that he would be his family’s eternal servant if Noah would allow him into the Ark (Yalkut Shimoni, Noach 55). The Talmud (ibid.) states that the rain waters of the Flood were actually boiling hot. Yet, the rain that fell upon Og while he held unto the Ark was miraculously cool, allowing him to survive. Perhaps Noah saw that Og had some sort of merit (after all, his grandfather was the one angel that repented). Noah therefore had mercy on Og, and made a special niche for Og in the Ark. This is how the giant survived the Flood.

A variant account suggests that Og survived by fleeing to Israel, since the Holy Land was the only place on Earth which was not flooded.

Abraham’s Servant

As promised, Og became the servant of Noah and his descendants. The Zohar (III, 184a) says that he served Abraham as well, and as part of his household, was also circumcised. As Rashi says (on Genesis 14:13), Og informed Abraham that his nephew Lot was kidnapped, and that the armies of Amraphel and his allies were terrorizing the region. Rashi quotes the Midrash in telling us that Og hoped Abraham would go into battle and perish, so that Og would be able to marry the beautiful Sarah. For informing Abraham, Og was blessed with wealth and longevity, but for his impure intentions, he was destined to die at the hands of Abraham’s descendents (Beresheet Rabbah 42:12).

Whatever the case, the giant soon fell into immorality. The Zohar continues that although he had initially taken the Covenant upon himself (by way of the circumcision), he had later broken that very same Covenant by his licentious behaviour. He used his physical abilities to become king over 60 large, fortified cities (Deuteronomy 3:4). When the nation of Israel passed by his territory, he gathered his armies to attack them.

It is said that Moses feared Og for a number of reasons: Og had lived for centuries, and was also circumcised, so Moses figured the giant had a great deal of merit. God told Moses not to worry, and gave Moses the strength to slay Og himself. As the famous story goes, Moses used a large ten-cubit (roughly 20 foot) weapon to jump ten cubits high in the air—and was only able to strike Og’s ankle! Still, it caused Og to trip over and be impaled by a mountain peak. (On that note, there is a little-known Midrash which states Og survived the Flood simply because he was so large, and the floodwaters only reached up to his ankles! See Midrash Petirat Moshe, 1:128)

It is important to remember once more the old adage that one who believes that the Midrash is false is a heretic, yet one who believes that the Midrash is literally true is a fool. It is highly unlikely that Og was actually so immense (especially considering that this would make him bigger than the dimensions of Noah’s Ark). The Torah tells us his bed was nine cubits long, which the most conservative opinions estimate to be closer to 13 feet, a far more reasonable number.

There are many more colourful stories about Og, including one where a Talmudic sage found his thigh bone and ran through it (Niddah 24b). Another suggests that Og is actually Eliezer, Abraham’s trusty servant (Yalkut Shimoni, Chayei Sarah 109). This is an intriguing possibility, and might help explain how Abraham and Eliezer alone were able to defeat the conglomeration of four massive armies (See Genesis 14, with Rashi).

Archaeologists have even found mention of Og in ancient Phoenician and Ugaritic texts. One clay tablet from the 13th century BCE (Ugarit KTU 1.108) is believed to be referring to him as Rapiu, or the last of the Rephaim—as the Torah states. It suggests that Og’s grandeur got the better of him, and he began to consider himself a god among puny men:

May Rapiu, King of Eternity, drink [w]ine, yea, may he drink, the powerful and noble [god], the god enthroned in Ashtarat, the god who rules in Edrei, whom men hymn and honour with music on the lyre and the flute, on drum and cymbals, with castanets of ivory, among the goodly companions of Kothar…

Perhaps this hubris was Og’s fatal flaw, and brought about his ultimate downfall.

Interestingly, there are also a number of dolmen found in the modern-day area that would have been Bashan. These dolmen are massive stone structures that were erected millennia ago, with some rocks weighing many tons and perplexing scholars as to how they were put together. It is thought that dolmen served as burial tombs, and perhaps have a connection to the tradition of giants living in the Bashan area.