The Haftarah for this week’s parasha, Vayishlach, is the entire book of Ovadiah. This is the shortest book in Tanakh, just one chapter of 21 verses. The entire text is a prophecy regarding what will happen to Edom. The Zohar (I, 171a) explains that Ovadiah alone was able to foresee what exactly will happen to Edom in the distance future because he was himself a convert from Edom! There is a bit of a debate whether this Ovadiah is the same as the Ovadiah that assisted Eliyahu in I Kings 18. Recall that the latter Ovadiah was a servant in the palace of the wicked King Ahab and his evil wife Jezebel: “When Jezebel was killing off the prophets of God, Ovadiah had taken a hundred prophets and hidden them, fifty to a cave, and provided them with food and drink.” (I Kings 18:4) The Talmud teaches us that for this incredible act of kindness and bravery, Ovadiah was himself blessed with the gift of prophecy (Sanhedrin 39b). That said, it is possible the two Ovadiahs were distinct individuals (or reincarnations of the same soul, in two different bodies). In fact, there are at least a dozen people across the Tanakh named “Ovadiah”!

Petra, in today’s Jordan

Ovadiah’s prophecy to Edom begins by promising its destruction: “I will make you least among nations, you shall be most despised.” (1:2) What did the Edomites do to deserve this? “Your arrogant heart has seduced you, you who dwell in clefts of the rock, in your lofty abode. You think in your heart: ‘Who can pull me down to earth?’” (1:3) The main Edomite stronghold in ancient times is what is today called Petra, the famous rock outcropping on the east side of the Jordan River. The Edomites believed themselves to be safe in their Petra fortress, and they grew arrogant, and then joined the Babylonians in attacking Jerusalem:

For the outrage against your brother Jacob, disgrace shall engulf you, and you shall perish forever. On that day when you stood aloof, when aliens carried off his goods, when foreigners entered his gates and cast lots for Jerusalem, you were as one of them. How could you gaze with glee on your brother that day, on his day of calamity! How could you gloat over the people of Judah on that day of ruin! How could you loudly jeer on a day of anguish! (1:10-12)

This is echoed in Psalm 137:7, which describes the tragic destruction of Jerusalem at the hands of the Babylonians, and says: “Remember, Hashem, against the Edomites the day of Jerusalem’s fall; how they cried ‘Strip her, strip her to her very foundations!’” The Edomite cruelly went along with the Babylonian catastrophe, the destruction of the Holy Temple, and the exile of the Judeans. And for that, God promised that they should “perish forever”. When did this happen?

The Hasmoneans, of Maccabee fame, conquered Edom (by then called Idumea) during the reign of King Yochanan Hyrcanus (r. 134-104 BCE, probably the same person called Yochanan Kohen Gadol in the Talmud—more in his identity here). The Romans later absorbed Idumea into their own empire, and in 6 CE incorporated it into the province of Judea. It was then that Edom completely ceased to exist as its own entity—Ovadiah’s prophecy was finally fulfilled. Henceforth, in rabbinic texts, “Edom” was instead used as a code word for the Roman Empire (to understand why, see the second part of the recent ‘Understanding Edom’ series, and ‘How Esau Became Rome’ in Volume Two of Garments of Light).

The Hasmoneans, of Maccabee fame, conquered Edom (by then called Idumea) during the reign of King Yochanan Hyrcanus (r. 134-104 BCE, probably the same person called Yochanan Kohen Gadol in the Talmud—more in his identity here). The Romans later absorbed Idumea into their own empire, and in 6 CE incorporated it into the province of Judea. It was then that Edom completely ceased to exist as its own entity—Ovadiah’s prophecy was finally fulfilled. Henceforth, in rabbinic texts, “Edom” was instead used as a code word for the Roman Empire (to understand why, see the second part of the recent ‘Understanding Edom’ series, and ‘How Esau Became Rome’ in Volume Two of Garments of Light).

That said, we know that the Tanakh often presents us with “double-level” prophecies, to be fulfilled in those contemporary days of the past, as well as in the far future. After all, at its core the Tanakh is not a historical text, but a prophetic one. It has relevance not just to the past, but for the present and future, too. We study Tanakh to better understand ourselves and our souls, and to understand the world around us. The Torah is a living text, and we view the world through the lens of Torah. Thus, Ovadiah’s prophecy was not just for the past, fulfilled two millennia ago, but also for the far future, for the End of Days, and we can use it to better understand our current reality.

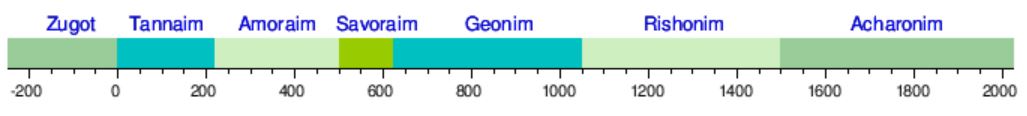

The Evolution of Edom & Rome

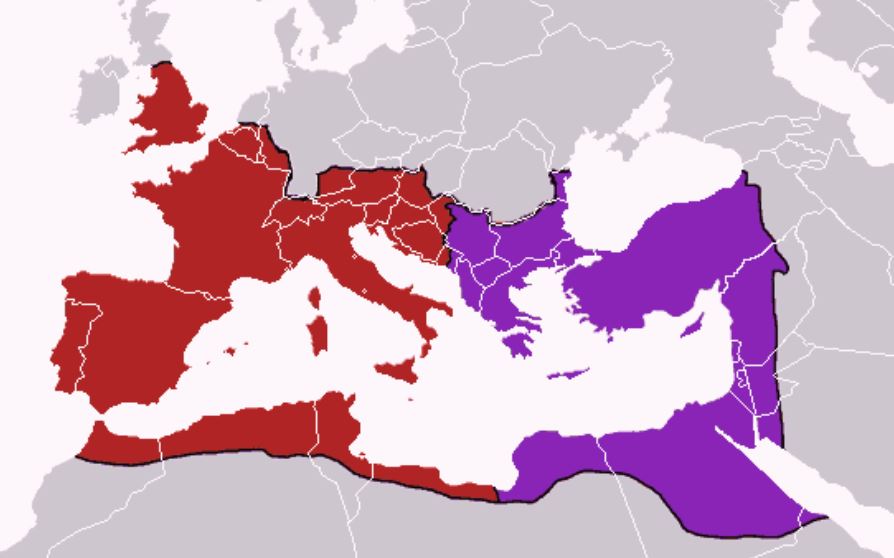

The key to understanding Ovadiah’s End Times vision is recognizing the identity of Edom. In Jewish texts, Edom is always used in reference to the Roman Empire. The original Roman Empire collapsed in 476 CE with the sack of Rome by the Germanic king Odoacer. However, the Roman Empire had previously been split into Western and Eastern halves. The West half was centered in Rome, while the Eastern half was centered in Constantinople. The Eastern half was not overrun by barbarians, and continued to exist—referred to today as the “Byzantine Empire”. Henceforth, its illustrious capital Constantinople was seen as the new, “second” Rome.

Division of the Roman Empire in 395 CE

In 1453 CE, the Ottomans conquered Constantinople, turning it into Istanbul. As the city became Islamified, the Orthodox Christian establishment fled—many of them to Moscow. They designated Moscow as the new, and “third” Rome. Henceforth, the leader of Russia was no longer called a “duke”, but rather czar, literally “caesar”. Russia adopted the Roman eagle as its symbol, and the red Edomite colours. This continued all the way through to the Red Army of the USSR, with its red flag and its epicentre at Red Square in Moscow. And so, although “Edom” certainly refers to the entire Western and Christian world, the leading oppressor of Edom is referred to more specifically as the “Third Rome”.

Indeed, we find that Russia and the USSR have been the longest and most consistent oppressor of Israel for centuries. Whether it’s the Pale of Settlement, the Cantonist Laws (that forcibly conscripted Jewish children to the Russian Army for decades of service), the pogroms, or the gulags; the USSR’s role in creating the “Palestinian” movement and training the PLO, or the KGB’s infiltration of the Israeli Knesset (discussed in this class), or Russia today supporting Hamas and Hezbollah (neither of which is designated a terrorist organization by Russia, unlike by nearly all Western countries). It was also in Russia that the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion was produced, inspiring generation after generation of antisemites and Jew-murderers.

So, while there may still be some debate in Jewish circles regarding who exactly is the “Third Rome” of the world today, it actually seems quite clear that all signs point to Moscow. Amazingly, the Talmud (Sanhedrin 98a) predicted that there would be three Romes, but not a fourth, and that Mashiach would come after the fall of the Third Rome. As explored in the past (in an essay here, and in the three-part video series on “Third Rome”), the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989 (or 5750) corresponded perfectly to the final possible starting point of the Ikvot haMashiach, the “End of Days” era leading up to the Messianic Age. With this in mind, we can understand Ovadiah’s prophecy and how it relates to today’s events.

Hamas, Hezbollah, Houthis

Ovadiah 1:3 accuses Edom of becoming arrogant, and feeling safe in their “lofty abode”. This could certainly apply to Russia, which has in recent years been arrogantly trying to conquer (or reconquer) neighbouring lands in Georgia, Crimea, and Ukraine. Perhaps the Russian regime feels safe in their vast and cold northern abode, knowing full well that no one has been able to defeat them in the past, not even the massive, powerful armies of Napoleon or Hitler. So, Russia arrogantly went to war with Ukraine, and thought it would be a quick “special operation”. Instead, it has turned into a full-blown proxy war against NATO, and Russia has suffered horrendous losses. They are now relying partly on cheaply-made Iranian drones and missiles, and on thousands of North Korean mercenaries who have not been able to help very much either. At the same time, support from allies like China and Belarus has been underwhelming. Ovadiah describes this all very well:

How thoroughly rifled is Esau, how ransacked his hoards! All your allies turned you back at the frontier; your own confederates have duped and overcome you; [those who ate] your bread have planted snares under you. He is bereft of understanding. (v. 6-7)

One of the Edomite allies that Ovadiah refers to are the “warriors of Teiman”, and Ovadiah says they will “lose heart” and faulter: v’hatu giborekha teiman! (v. 9) It is interesting to point out that one of the so-called 3 H’s that Russia supports is the Houthis of Yemen, ie. Teiman (the other two are Hamas and Hezbollah). Ovadiah even gives a cryptic allusion to this in saying those murderers in Teiman will be hatu—Houthis! More incredibly, the very next verse mentions Hamas: “For the violence against your brother Jacob, disgrace shall engulf you, and you shall perish forever.” (v. 10) The word for “violence” here, of course, is hamas. Ovadiah goes on to accuse Edom of supporting those who came against Israel:

On that day when you stood aloof, when aliens carried off his goods, when foreigners entered his gates and cast lots for Jerusalem, you were as one of them. How could you gaze with glee on your brother that day, on his day of calamity! How could you gloat over the people of Judah on that day of ruin! How could you loudly jeer on a day of anguish! How could you enter the gate of My people on its day of disaster, gaze in glee with the others on its misfortune on its day of disaster, and lay hands on its wealth on its day of disaster! (v. 12-14)

Edom stood by while Israel was being slaughtered. The terrorists came to “cast lots for Jerusalem”. Recall that the name Hamas chose for their day of terror on October 7 was “Al-Aqsa Flood”—they believed they were coming to “liberate” Al-Aqsa, ie. Jerusalem. Ovadiah says Edom played a role in this because they were concerned for their own wealth. Indeed, many have pointed out that Russia had the most to gain from October 7: In the days leading up to it, all the talk in the media was about Israel’s impending peace deal with Saudi Arabia—which would include oil and gas pipelines through Israel to Europe that would undermine Russia’s own supply to Europe (Russia’s main source of wealth). Russia had to stop the deal to protect its oil and gas riches. It worked, as October 7 quashed the Israel-Saudi deal.

At the same time, Russia wanted to get the world off its back for Ukraine, and this too happened post-October 7, with the world quickly forgetting about Ukraine and turning all of its attention to Gaza. Funding and donations for Ukraine subsequently dropped in dramatic fashion, the world’s money now channeled to Gaza instead. (Ukrainian officials complained greatly about this, to deaf ears!) For Russia, October 7 was a win-win. And it also just happened to be Putin’s birthday!

Ovadiah concludes his prophecy by relaying God’s promise that the wicked Edomite regime would be destroyed, and would never again bother Israel. The flame of Israel will be rekindled, “the House of Jacob shall be fire, and the House of Joseph flame, and the House of Esau shall be straw…” (v. 18) and we will see the eventual positive outcome of this tragic war, with Israel reclaiming “the Negev and Mount Esau as well, the Shephelah and Philistia. They shall possess the Ephraimite country and the district of Samaria, and Benjamin along with Gilead.” Remember that Philistia is Gaza, and the Ephraimite country, Samaria, and Benjamin makes up most of the “West Bank”, while Gilead refers to the general area around the Golan Heights. We are seeing this happening right before our eyes now.

Finally, “the exile of the Children of Israel, that have gone to be kna’anim as far as Tzarfat, and the Jerusalemite exile as far as Sepharad, shall possess the towns of the Negev.” (v. 20) In the times of Ovadiah, Tzarfat and Sepharad referred to places north of Israel, in what is today Lebanon and Turkey. Over time, just as Edom became the Roman Empire, Tzarfat became France and Sephard became Spain. Interestingly, when looking back at Jewish texts from around 1000 years ago, we find that there is mention of Jewish communities distinct from Ashkenazi and Sephardi, called Tzarfati Jews and Kna’ani Jews. The Tzarfati Jews are a bit better known because of great figures like Rashi, but we hear very little of the Kna’ani Jews. Who were they?

“Kna’ani” was the label for those Jews living in Eastern Europe, among Slavic peoples. Intriguingly, they were called Kna’ani because in Biblical parlance “Canaanite” was synonymous with being a “slave” (since Canaan was cursed with slavery). The Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe were a major source of slaves in Roman and Medieval times; in fact, the root of the word “slave” is slav! This is why Jews living among the Slavs were nicknamed “Kna’ani”. Over time, the Kna’ani Jewish community fused together with the Ashkenazi community originally rooted in Germany, and most of the Tzarfati community in France (while many in southern France fused with their nearby Sephardis). Meanwhile, following the Spanish Expulsion the Sephardi community fused together with North African and Mizrachi communities. Thus, in effect, when Ovadiah speaks of Kna’ani, Tzarfati, and Sephardi Judeans in exile, he is really referring to all the major groups of Jews today.

Very soon, all Jews still in exile will return to a stronger and larger and more prosperous Israel, “For liberators shall march up on Mount Zion to wreak judgment on Mount Esau; and dominion shall be God’s.” (v. 21) May it come speedily and in our days.

Shabbat Shalom!