This week’s parasha (in the diaspora) is Korach. In a traditional Chumash, at the end of each parasha there is a “Masoretic note” that provides a mnemonic to remember how many verses are in the parasha. This mnemonic is not random, and has a deep significance of its own. The mnemonic for parashat Korach, which has 95 verses, is “Daniel” (דניאל), which has a numerical value of 95. What hidden connection were the Masoretes concealing in this note? What does Korach have to do with Daniel?

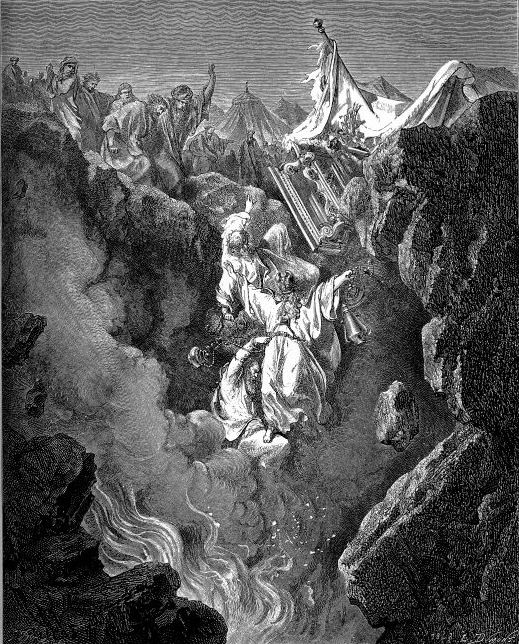

“Death of Korah, Dathan, and Abiram” by Gustave Doré

At the heart of Korach’s rebellion was the argument that “all of Israel is holy” (Numbers 16:3). He accused Moses of nepotism and elitism, saying that Moses and his family took over the top positions and placed themselves above the commoners. Rashi comments (on 16:6) that Moses actually agreed with Korach to some extent, and said he also wished that everyone could be on the same spiritual plane. This is why he told Korach and his followers to take their own incense pans and attempt to make an offering like a High Priest. Moses’ defence was that, of course, he was only fulfilling God’s will.

In the absolute sense, Korach’s argument was not wrong, it was just not l’shem shamayim (as our Sages state in Avot 5:17). He was not rebelling for Heaven’s sake, or to truly elevate the people, but for his own glory and ulterior motives. This is why he failed. Truthfully, though, God did intend for all of Israel to be on the same plane—eventually. The Wilderness generation was not yet ready for it, but in time God would lead Israel towards oneness and equality. And when did this happen? Precisely in the time of Daniel!

After the First Temple was destroyed, Israel was exiled to the melting pot that was Babylon. Outside the Holy Land and without a Temple, the kohen had no role, and being a priest became mostly irrelevant. Instead, Babylon saw the rise of the chakham, the Jewish sage. The educated scholars knew how to adapt and what to do, and how to lead the community in exile. Of course, being a chakham was not based on birthright or genealogy, it was entirely based on merit and scholarship. Anyone could be a chakham!

Meanwhile, in a few short generations, the old Israelite tribal affiliations were forgotten. In Babylon, everyone became a Yehudi, simply a Judahite or “Jew”. We read in Megillat Esther that Mordechai was a Benjaminite, yet he is first called an Ish Yehudi before the text mentions that he is an Ish Yemini. His primary identity was that he was a Jew, not a Benjaminite! Mordechai knew his Benjaminite lineage because he was one of the elders and original exiles, but the younger generations that followed quickly forgot their detailed backgrounds. In short, everyone became a Jew (even the priestly Levites!) and everyone now had the potential to be a great chakham and leader, like Mordechai himself.

Mordechai’s contemporary was Daniel, another great sage who made sure to keep Jewish law despite serving the Babylonian government (as we read in the first chapter of the Book of Daniel), and worked tirelessly to ensure Judaism would not be forgotten in exile. In fact, Daniel plays a hidden role in the Megillah, as our Sages identified him with the character called Hatakh (Esther 4:5), palace attendant of Queen Esther (Megillah 15a). Hatakh is the hidden hero in the story, delivering the secret communications between Esther and Mordechai, and helping her confront Haman. There is a beautiful gematria here, too, because Haman (המן) is 95, as is Daniel (דניאל), suggesting numerically that Daniel “neutralized” Haman.

So, it was in the era of Daniel that Korach’s case for an equal Israel was realized. This is the deeper meaning for why parashat Korach has exactly 95 verses, and this is why the Masoretic note reminds us about Daniel at the end of Korach’s parasha.

Shabbat Shalom!