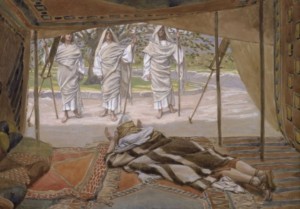

This week’s parasha, Vayera, begins with Abraham sitting outside his tent just days after circumcising himself at the age of 99. We would expect him to be weak and frail at this moment, yet he is spry and full of energy. The Torah tells us that it was a very hot day (Genesis 18:1), and the Sages explain (as cited by Rashi on the verse) that God deliberately made it hot so that Abraham should not have any visitors bother him during his recovery. Yet, Abraham was more pained by the lack of visitors than he was from the circumcision! So, God sent him three angelic guests.

Abraham immediately sprung into action, bringing water for his guests to wash their feet, and cooking up a feast. Abraham served his guests “cream and milk and the calf that he had made, and he placed [them] before them, and he was standing over them under the tree, and they ate.” (Genesis 18:8) As discussed in the past, the Sages were puzzled at the fact that Abraham served both dairy and meat at the same meal. Although he lived before the official giving of the Torah, and therefore was not bound by Torah law, nonetheless we would expect him to observe the eternal Torah anyway. Jewish tradition holds that the Patriarchs also observed the Torah through an oral tradition and through their direct prophetic knowledge from God.

One solution to the problem comes from another tradition that Abraham had received the secret wisdom of Creation, and was actually the originator of Sefer Yetzirah, the “Book of Formation”. He knew how to use mystical powers to create things out of thin air. Hence, when the Torah says “the calf that he had made [asher asah]” it means that he literally made the calf! Since he had made this hunk of meat, it was never a living animal, and possessed no soul, so it was totally pareve, and he could serve it with “cream and milk”. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 65b) tells us that Rav Chanina and Rav Oshaia would study Yetzirah and similarly create a calf out of thin air which they then consumed.

Meanwhile, in last week’s parasha we saw how Abraham took on the united armies of four powerful kings. The Torah tells us that he fought them off with just 318 of his men (Genesis 14:14). If this wasn’t enough of a miracle, the Sages say (as cited by Rashi on the verse) that Abraham really didn’t have 318 men. Rather, 318 is the gematria of “Eliezer” (אליעזר), Abraham’s devoted servant. It was just Abraham and Eliezer taking on an entire army! How could they do this? The Talmud (Sanhedrin 109a) says that when Abraham would throw dust and straw it would transform into swords and arrows in mid-air. That’s quite the superpower!

Judaism is full of such feats of superpower, whether it’s Jacob pushing off a well-stone on his own (Genesis 29:1-10)—when normally it required a team of shepherds—or Samson crushing a thousand Philistines with a jawbone (Judges 15), or figures like Eliezer and Eliyahu employing kefitzat haderekh, “leaping” or “teleporting” across vast distances (see Sanhedrin 95a-b and Kiddushin 40a). It therefore isn’t surprising that the modern “pantheon” of superheroes was crafted almost entirely by Jewish writers and artists. Continue reading