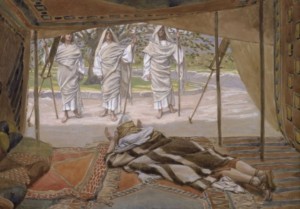

‘Abraham and the Three Angels’ by James Tissot

This week’s parasha, Vayera, begins by telling us that following Abraham’s circumcision, he was “sitting at the entrance of the tent as the day was hot.” (Genesis 18:1) The Ba’al HaTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, 1269-1340) offers several interesting possibilities as to why the Torah had to mention this seemingly superfluous detail. One of the answers is that k’chom hayom, the heat of the day, is actually alluding to the heat of Hell. As is characteristic of the Ba’al HaTurim, he proves it mathematically, pointing out that the numerical value of k’chom hayom (כחם היום) is equivalent to “this is in Gehinnom” (זהו בגיהנם), when including the additional kollel.

The Ba’al haTurim also draws on a Talmudic teaching (Eruvin 19a) that Abraham sits at the “entrance” to Gehinnom and pulls out all who are circumcised from there! There is an exception to this, though, for being “circumcised” is more than just the one-time passive active of getting circumcised. A man also has to “uphold” his circumcision, meaning not to abuse that organ. Anyone who was promiscuous over the course of their life has their foreskin grow back in Gehinnom—and those people Abraham does not save!

That said, what exactly is Gehinnom? Is it the equivalent of “Hell”? Does Judaism have a concept of such an eternal place of torment? It is common to hear that Judaism does not have such a notion, and that the Tanakh does not describe such a place. Yet, later Jewish literature is actually quite rich with discussion of a hellish torment of some sort for certain wicked individuals in the afterlife. What is the truth? Continue reading →