Vestments of the kohen and kohen gadol

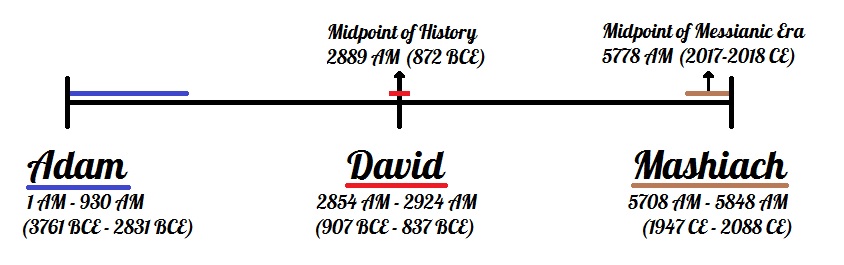

This week’s parasha, Tetzave, continues to outline the items necessary for the Mishkan, or Tabernacle, starting with the Menorah and going into a detailed description of the priestly vestments. One of the materials necessary for the holy garments is tola’at shani, commonly translated as “crimson wool”. This was a deep red fabric apparently derived from some kind of insect or worm (which is what the Hebrew “tola’at” means). The Torah speaks of this material in multiple places and in multiple contexts. Today, wearing a “tola’at shani”-like red string on the wrist has become very popular among those calling themselves “Kabbalists” and even by secular Jews and non-Jews. What is the significance of the red fibre, and is there any real spiritual meaning to the red string bracelet?

The First Red String

The earliest mention of a red string is in Genesis 38:27-30, where Tamar gives birth to her twin sons Peretz and Zerach:

And it came to pass in the time of her labour that, behold, twins were in her womb. And in her labour, one hand emerged, and the midwife took a red string [shani] and tied it to his hand saying, “This one came out first.” And he drew back his hand, and behold, his brother came out, and she said: “With what strength have you breached [paratz] yourself?” so his name was called Peretz. And afterward came out his brother that had the red string upon his hand, and his name was called Zerach.

Here, the red string is simply used to designate the firstborn. It didn’t work out as planned, for the other twin ended up coming first. The strong Peretz would go on to be the forefather of King David, and therefore Mashiach, who is sometimes called Ben Partzi. Clearly, wearing the red string wasn’t much of an effective charm for Zerach.

Temple Rituals

In addition to being used in the garments of the priests and various Temple vessels, tola’at shani was employed in a number of sacrificial rituals. In Leviticus 14 we read how someone who had healed from tzara’at, loosely translated as “leprosy”, would bring an offering of two birds which were dipped in a mixture containing the red dye. From this we see that tola’at shani (or shni tola’at, as it appears here) is not necessarily the string itself, but simply the red dye extracted from the insect. Similarly, the red dye was used in the preparation of the parah adumah, “Red Cow”, mixture (Numbers 19) which was used to purify the nation from the impurity of death.

The Talmud (Yoma 67a) describes how a red string was tied to the scapegoat on Yom Kippur. Recall that on Yom Kippur two goats were selected, one being slaughtered and the other being sent off into the wilderness, “to Azazel”. This “scapegoat” had a red string attached to it, and if the string turned white the people would know that their sins had been forgiven, as Isaiah 1:18 states: “…though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool.” Here, then, the red string represents the sin of the people, bound to the scapegoat going to Azazel. If it turned white, it was a good sign, whereas if the string remained red it meant God was unhappy with the nation. Indeed, the Talmud (Yoma 39b) states that in the last forty years before the Second Temple was destroyed, the red string never once turned white.

Red in Kabbalah

In mystical texts, red is typically the colour of Gevurah or Din, severity and judgement. It was therefore generally discouraged to wear red. The Kabbalists often wore garments of all white, and this is still the custom during the High Holidays, a time of particularly great judgement. It was only centuries later that the Chassidic rebbe known as Minchat Eliezer (Rabbi Chaim Elazar Spira of Munkacz, 1868-1937) wrote how having a red cloth may serve to ward off judgement and severity. Another Chassidic rebbe, the Be’er Moshe (Rabbi Moshe Stern of Debreczin, 1890-1971) wrote that he remembered seeing people wear red strings as a child, but did not know why. Still, this does not appear to have been a very popular practice then, nor is it much of a custom among Chassidim now.

1880 Illustration of Rachel’s Tomb

Rather, the red string today has been popularized by The Kabbalah Centre and similar “neo-Kabbalah” movements that cater as much to non-Jews as to secular Jews. The Kabbalah Centre explains that the bracelets are made by taking a long red thread and winding it around Rachel’s Tomb seven times. The thread is then cut into wrist-size lengths, and if worn on the “left wrist, we can receive a vital connection to the protective energies surrounding the tomb of Rachel.” It is not clear where The Kabbalah Centre took this practice from. They claim that the red string wards off the evil eye. While they cite certain passages from the Zohar regarding the evil eye, there doesn’t seem to be any connection to a red string specifically.

The Zohar (II, 139a) does state in one place that the blue tekhelet represents God’s Throne, as is well-known, which means judgement, whereas the red shani is what emerges from the Throne and overpowers the judgement, thus bringing protection upon Israel. The Zohar relates shani to Michael, the guardian angel of Israel, and uses the metaphor of a worm eating through everything to explain the tola’at shani as eating up negative judgement. This is why the famous song Eshet Chayil (Proverbs 31) states that a “woman of valour” has her whole house dressed in shanim (v. 21). She guards her household in this way. (It should be noted that in this passage the Zohar states it is gold which represents Gevurah, and silver represents Chessed. White and red, meanwhile, appear to be aspects within the sefirah of Yesod.)

So, perhaps there is something to wearing a red string.

Bringing Back Shani

The Zohar does not speak of any red string at all, and instead explains the mystical power of the red dye called shani. It is the dye itself that has power, as we see from the Temple rituals noted above. It is well-known that the blue tekhelet dye comes from a certain mollusc or sea snail called chilazon. From where does shani come?

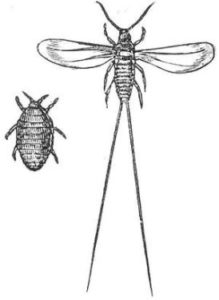

A female and male cochineal bug.

Professor Zohar Amar of Bar Ilan University researched the subject in depth and concluded that tola’at shani is similar to the cochineal insect, famous for producing the red dye carmine (E120) which is extensively used in the food industry. After a round-the-world search, it turned out that a cochineal-like insect is found in Israel as well, and grows on oak trees.

While the cochineal insect is native to South America (where most of the carmine is still produced), its Mediterranean cousin is the oak-dwelling kermes insect. Indeed, kermes was used across the Mediterranean world for millennia, being particularly prized in Greek, Roman, and medieval society. It is best known for its ability to dye wool extremely well. Jerusalem’s Temple Institute was convinced of the professor’s findings, and has begun harvesting the bugs and their red dye in order to produce authentic priestly vestments, as outlined in the Torah.

In light of this, a genuine red string “kabbalah” bracelet—with the protective powers mentioned in the Zohar—would undoubtedly have to be made of wool dyed with kermes red. And according to the Zohar, it probably shouldn’t be worn on the left wrist at all, but instead on the right leg, the body part which the Zohar (II, 148a) states that shani corresponds to.

Imitating Pagans

Judaism is very sensitive about not imitating the ways of the pagans, or darkei Emori. One example of this, as we wrote in the past, is kapparot, which the Ramban (among others) called an idolatrous practice. The Tosefta (Shabbat, ch. 7) has a list of practices that are considered darkei Emori, and one of them is “tying a red string on one’s finger”. So, already two millennia ago it seems there were Jews tying red strings on their body, and the Tosefta (which is essentially equivalent to the Mishnah) forbids it.

The Hindu kalava looks suspiciously similar to the “kabbalah” red string.

In fact, Hinduism has a custom to wear a red string called kalava around one’s wrist in order to ward off evil. This is precisely what The Kabbalah Centre claims their red string accomplishes. Based on this alone it would be best to avoid wearing such a red string. The Lubavitcher Rebbe was one of the recent authorities who stated that the red string should not be worn due to darkei Emori. Factoring in that the red string has no basis in the Zohar or any traditional Jewish mystical text is all the more reason to stay away from this practice.

The above is an excerpt from Garments of Light, Volume Two. Get the book here!