This week’s parasha is Ki Tisa, in which we read of Moses’ return from Mt. Sinai where he had spent forty days with God. During that time, he had composed the first part of the Torah and received the Two Tablets. The Talmud (Menachot 29b) tells us of another incredible thing that happened:

…When Moses ascended on High, he found the Holy One, Blessed be He, sitting and tying crowns on the letters of the Torah. Moses said before God: “Master of the Universe, who is preventing You from giving the Torah [without these additions]?” God said to him: “There is a man who is destined to be born after many generations, and Akiva ben Yosef is his name. He is destined to derive from each and every tip of these crowns mounds upon mounds of halakhot.” [Moses] replied: “Master of the Universe, show him to me.” God said to him: “Return behind you.”

Moses went and sat at the end of the eighth row [in Rabbi Akiva’s classroom] and did not understand what they were saying. Moses’ strength waned, until [Rabbi Akiva] arrived at the discussion of one matter, and his students said to him: “My teacher, from where do you derive this?” [Rabbi Akiva] said to them: “It is an halakha transmitted to Moses from Sinai.” When Moses heard this, his mind was put at ease…

Up on Sinai, Moses saw a vision of God writing the Torah—this is how Moses himself composed the Torah, as he was shown what to inscribe by God—and he saw God adding the little tagim, the crowns that adorn certain Torah letters. Moses was puzzled by the crowns, and asked why there were necessary. God replied that in the future Rabbi Akiva would extract endless insights from these little crowns.

Up on Sinai, Moses saw a vision of God writing the Torah—this is how Moses himself composed the Torah, as he was shown what to inscribe by God—and he saw God adding the little tagim, the crowns that adorn certain Torah letters. Moses was puzzled by the crowns, and asked why there were necessary. God replied that in the future Rabbi Akiva would extract endless insights from these little crowns.

Moses then asked to see Rabbi Akiva, and was permitted to sit in on his class. Moses could not follow the discussion! In fact, the Talmud later says how Moses asked God: “You have such a great man, yet you choose to give the Torah through me?” At the end of the lesson, Rabbi Akiva’s students ask him where he got that particular law from, and he replied that it comes from Moses at Sinai. Moses was comforted to know that even what Rabbi Akiva would teach centuries later is based on the Torah that Moses would compose and deliver to Israel.

This amazing story is often told to affirm that all aspects of Torah, both Written and Oral, and those lessons extracted by the Sages and rabbis, stems from the Divine Revelation at Sinai, and from Moses’ own teachings. It is a central part of Judaism that everything is transmitted in a chain starting from Moses at Sinai, down through the prophets, to the Anshei Knesset HaGedolah, the “Men of the Great Assembly” and the earliest rabbis, all the way through to the present time.

What is usually not discussed about this story, though, is the deeper and far more perplexing notion that Moses travelled through time! The Talmud does not say that Moses saw a vision of Rabbi Akiva; it says that he literally went and sat in his classroom. He was there, sitting inconspicuously at the end of the eighth row. As a reminder, Moses received the Torah in the Hebrew year 2448 according to tradition, which is 3331 years ago. Rabbi Akiva, meanwhile, was killed during the Bar Kochva Revolt, 132-136 CE, less than 2000 years ago. How did Moses go 1400 years into the future?

Transcending Time and Space

In his commentary on Pirkei Avot (Magen Avot 5:21), Rabbi Shimon ben Tzemach Duran (1361-1444) explains:

Moshe Rabbeinu, peace be upon him, while standing on the mountain forty days and forty nights, from the great delight that he had learning Torah from the Mouth of the Great One, did not feel any movement, and time did not affect him at all.

As we read at the end of this week’s parasha, Moses “was there with God for forty days and forty nights; he ate no bread and drank no water, and He inscribed upon the tablets the words of the Covenant…” (Exodus 34:28) At Sinai, Moses had no need for any bodily functions. Rabbi Duran explains that from his Divine union with God, Moses transcended the physical realm. In such a God-like state, he was no longer subject to the limitations of time and space.

In this regard, Moses became like a photon of light. Modern physics has shown that light behaves in very strange ways, and does not appear to be subject to time and space. Fraser Cain of Universe Today explains how

From the perspective of a photon, there is no such thing as time. It’s emitted, and might exist for hundreds of trillions of years, but for the photon, there’s zero time elapsed between when it’s emitted and when it’s absorbed again. It doesn’t experience distance either.

Light transcends time and space. In this way, Moses was like light. And this is quite fitting, for this week’s parasha ends with the following (Exodus 34:29-33):

And it came to pass when Moses descended from Mount Sinai, and the Two Tablets of the Testimony were in Moses’ hand when he descended from the mountain, and Moses did not know that the skin of his face had become radiant while He had spoken with him. And Aaron and all the children of Israel saw Moses, and behold, the skin of his face had become radiant, and they were afraid to come near him… When Moses had finished speaking with them, he placed a covering over his face.

Moses glowed with a bright light, so much so that the people couldn’t look at him, and he would wear a mask over his face. Moses had become light. And light doesn’t experience time and space like we do. There is something divine about light. It therefore isn’t surprising that the Kabbalists referred to God as Or Ain Sof, “light without end”, an infinite light, or simply Ain Sof, the “Infinite One”. Beautifully, the gematria of Ain Sof (אין סוף) is 207, which is equal to light (אור)!

Travelling to the Future

While Moses was instantly teleported into the future, we currently have no scientifically viable way for doing so. However, the notion of travelling into the future is a regular fixture of modern science fiction, and the way it usually presents itself is through some form of “cryosleep”. This is when people are either frozen or placed into a state of deep sleep, or both, for a very long time (usually because they are flying to distant worlds many light years away), and are reanimated in the distant future. For this there is a good scientific foundation, as there are species of frogs in Siberia, for example, that are able to freeze themselves for the winter, and thaw in the spring. They can do this without compromising the integrity of their cellular structure, in a process not yet fully understood. If we could mimic this biological process, then humans, too, could potentially freeze themselves for long periods of time, “thawing” in the future. And this, too, has a precedent in the Talmud (Ta’anit 23a):

[Honi the Circle-Drawer] was throughout the whole of his life troubled about the meaning of the verse, “A song of ascents, when God brought back those that returned to Zion, we were like them that dream.” [Psalms 126:1] Is it possible for a man to dream continuously for seventy years? One day he was journeying on the road and he saw a man planting a carob tree. He asked him: “How long does it take [for this tree] to bear fruit?” The man replied: “Seventy years.” He then further asked him: “Are you certain that you will live another seventy years?” The man replied: “I found [ready-grown] carob trees in the world; as my forefathers planted these for me so I too plant these for my children.”

Honi sat down to have a meal and sleep overcame him. As he slept a rocky formation enclosed upon him which hid him from sight and he continued to sleep for seventy years. When he awoke he saw a man gathering the fruit of the carob tree and he asked him: “Are you the man who planted the tree?” The man replied: “I am his grandson.” Thereupon he exclaimed: “It is clear that I slept for seventy years!” He then caught sight of his donkey who had given birth to several generations of mules, and he returned home. He there enquired: “Is the son of Honi the Circle-Drawer still alive?” The people answered him: “His son is no more, but his grandson is still living.” Thereupon he said to them: “I am Honi the Circle-Drawer”, but no one would believe him.

He then went to the Beit Midrash and overheard the scholars say: “The law is as clear to us as in the days of Honi the Circle-Drawer”, for whenever he used to come to the Beit Midrash he would settle for the scholars any difficulty that they had. Whereupon he called out: “I am he!” but the scholars would not believe him nor did they give him the honour due to him. This hurt him greatly and he prayed [for death] and he died…

“Honi HaMeagel”, by Huvy. Honi is famous for drawing a circle in the ground around him and not moving away until God would make it rain. Josephus wrote that Honi was killed during the Hasmonean civil war, around 63 BCE. The Maharsha (Rabbi Shmuel Eidels, 1555-1631) said that people thought he was killed in the war, but actually fell into a deep sleep as the Talmud records.

Honi HaMa’agel, “the Circle-Drawer”, who was renowned for his ability to have his prayers answered, entered a state of deep sleep for seventy years and thereby journeyed to the future! This type of time travel is, of course, not true time travel, and he was unable to go back to his own generation. He prayed for death and was promptly answered.

Travelling back in time, meanwhile, presents far more interesting challenges.

Back to the Future

In 2000, scientists at Princeton University found evidence that it may be possible to exceed the speed of light. As The Guardian reported at the time, “if a particle could exceed the speed of light, the time warp would become negative, and the particle could then travel backwards in time.” This is one of several ways proposed to scientifically explain the possibility of journeying back in time.

The problem with this type of travel is as follows: what happens when a person from the future changes events in the past? The result may be what is often referred to as a “time paradox” or “time loop”. The classic example is a person who goes back to a time before they were born and kills their parent. If they do so, they would never be born, so how could they go back in time to do it?

Remarkably, just as I took a break from writing this, I saw that my son had brought a book from the library upstairs. Out of over 500 books to choose from, he happened to bring Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Now, he is far too young to have read it, or to even known who Harry Potter is. And yet, this is the one book in the Harry Potter series—and possibly the one book in our library—that presents a classic time paradox!

In Prisoner of Azkaban, we read how Harry is about to be killed by a Dementor when he is suddenly saved by a mysterious figure who is, unbeknownst to him, his own future self. After recovering from the attack, he later gets his hands on a “time turner” and goes back in time. It is then that he sees his past self about to be killed by a Dementor, and saves his past self. The big problem, of course, is that Harry could have never gone back in time to save himself had he not already gone back in time to save himself in the first place!

Perhaps a more famous example is James Cameron’s 1984 The Terminator. In this story, John Connor is a future saviour of humanity who is a thorn in the side of the evil, world-ruling robots. Those evil robots decide to send one of their own back to a time before John Connor was born in order to kill his mother—so that John could never be born. Aware of this, Connor sends one of his own soldiers back in time to protect his mother. The soldier and the mother fall in love, and the soldier impregnates her, giving birth to John Connor! In other words, future John Connor sent his own father back in time to protect his mother and conceive himself! This is a time paradox.

Could we find such a time paradox in the Torah? At first glance, there doesn’t appear to be anything like this. However, a deeper look reveals that there may be such a case after all.

When God Wanted to “Kill” Moses

In one of the most perplexing passages in the Torah, we read that when Moses took his family to head back to Egypt and save his people, “God encountered him and sought to kill him.” (Exodus 4:24) To save Moses, his wife Tziporah quickly circumcises their son, sparing her husband’s life. The standard explanation for this is that Moses’ son Eliezer was born the same day that he met God for the first time at the Burning Bush. Moses spent seven days communicating with God, then descended on the eighth day and gathered his things to go fulfil his mission.

However, the eighth day is when he needed to circumcise his son, as God had already commanded his forefather Abraham generations earlier. Moses intended to have the brit milah when they would stop at a hotel along the way, but got caught up with other things. An angel appeared, threatening Moses for failing to do this important mitzvah, so Tziporah took the initiative and circumcised her son. Alternatively, some say it was the baby whose life was at risk.

Whatever the case, essentially all the commentaries agree that God had sent an angel to remind Moses of the circumcision. Who was that angel? It may have been a persecuting angel, and some say he took the form of a frightening snake. Others, like the Malbim (Rabbi Meir Leibush Weisser, 1809-1879) say it was an “angel of mercy” as Moses was entirely righteous and meritorious. Under the circumstances, one’s natural inclination might point to it being the angel in charge of circumcision, as suggested by Sforno (Rabbi Ovadiah ben Yakov, 1475-1550). Who is the angel in charge of circumcision? Eliyahu! In fact, Sforno proposes that the custom of having a special kise kavod, chair of honour, or “chair of Eliyahu” (though Sforno doesn’t say “Eliyahu” by name), might originate in this very Torah passage. Every brit milah today has such an Eliyahu chair, for it is an established Jewish tradition that the prophet-turned-angel Eliyahu visits every brit.

Yet, Eliyahu could not have been there at the brit of Moses’ son, for Eliyahu would not be born for many years! Eliyahu lived sometime in the 9th century BCE. He was a prophet during the reign of the evil king Ahab and his even-more-evil wife Izevel (Jezebel). The Tanakh tells us that Eliyahu never died, but was taken up to Heaven in a fiery chariot (II Kings 2). As is well-known, he transformed into an angel.

The Zohar (I, 93a) explains that when Eliyahu spoke negatively of his own people and told God that the Jews azvu britekha, “have forsaken Your covenant” (I Kings 19:10), God replied:

I vow that whenever My children make this sign in their flesh, you will be present, and the mouth which testified that the Jewish people have abandoned My covenant will testify that they are keeping it.

He henceforth became known as malakh habrit, “angel of the covenant” (Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer, 29), a term first used by the later prophet Malachi (3:1).

If Eliyahu is Malakh haBrit, and is present at every circumcision, does this only apply to future circumcisions after his earthly life, or all circumcisions, even those before his time? As an angel that is no longer bound by physical limitations, could he not travel back in time and be present at brits of the past, too? God certainly does transcend time and space, and exists in past, present, and future all at once. This is in God’s very name, a fusion of haya, hoveh, and ihyeh, “was, is, will be”, all in one (see Zohar III, 257b, as well as the Arizal’s Etz Chaim, at the beginning of Sha’ar Rishon, anaf 1). And we already saw how God could send Moses to the distant future and bring him right back to the past. Could He have sent Eliyahu back to the brit of Moses’ son? Such a scenario would result in a classic time loop. How could Eliyahu, a future Torah prophet, save Moses, the very first Torah prophet? Eliyahu could not exist without Moses!

It is important to note here that there were those Sages who believed that Eliyahu was always an angel, from Creation, and came down into bodily form for a short period of time during the reign of Ahab. This is why the Tanakh does not describe Eliyahu’s origins. It does not state who his parents were, or even which tribe he hailed from. Others famously state that “Pinchas is Eliyahu”, ie. that Eliyahu was actually Pinchas, the grandson of Aaron. Pinchas was blessed with eternal life, and after leaving the priesthood, reappeared many years later as Eliyahu to save the Jewish people at a difficult time. He was taken up to Heaven alive as God promised. In the Torah, we read how God blessed Pinchas with briti shalom (Numbers 25:12). Again, that key word “brit” appears—a clue that Pinchas would become Eliyahu, malakh habrit.

While it is hard to fathom, or accept, the possibility of an Eliyahu time paradox, there is one last time paradox that deserves mention. And on this time paradox, all of our Sages do agree…

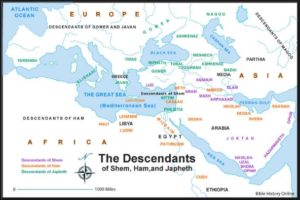

One of Noah’s descendants is named Ashkenaz (Genesis 10:3). He is a grandson of Yefet, whose children all seem to have inhabited territories in Asia Minor and Armenia. Ashkenaz, too, is in that vicinity. Even in the time of the prophet Jeremiah centuries later, Ashkenaz was a kingdom in Turkey: “Raise a banner in the land, blow the shofar among the nations, prepare the nations against her, call together against her the kingdoms of Ararat, Minni, and Ashkenaz…” (Jeremiah 51:27) The prophet goes on to call on these and other powers in the area to come upon Babylon. Ashkenaz is one of the Turkish kingdoms bordering Babylon to the north, along with Ararat.

One of Noah’s descendants is named Ashkenaz (Genesis 10:3). He is a grandson of Yefet, whose children all seem to have inhabited territories in Asia Minor and Armenia. Ashkenaz, too, is in that vicinity. Even in the time of the prophet Jeremiah centuries later, Ashkenaz was a kingdom in Turkey: “Raise a banner in the land, blow the shofar among the nations, prepare the nations against her, call together against her the kingdoms of Ararat, Minni, and Ashkenaz…” (Jeremiah 51:27) The prophet goes on to call on these and other powers in the area to come upon Babylon. Ashkenaz is one of the Turkish kingdoms bordering Babylon to the north, along with Ararat.

One popular explanation for the Turkey-Ashkenaz connection points to the Kingdom of Khazaria. This was a wealthy and powerful kingdom that ruled the Caucasus, southern Russia, and parts of Turkey and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages. Historians credit the Khazars with checking the rapid Arab conquest, and preventing a Muslim takeover of Europe from the East. It is said that around 740 CE, King Bulan grew tired of his people’s backwards pagan beliefs and converted to Judaism. According to legend, he had invited representatives of the major faiths to argue their case, and concluded that Judaism was the true faith. (This is the basis of Rabbi Yehuda haLevi’s [c. 1075-1141] famous text, Kuzari.)

One popular explanation for the Turkey-Ashkenaz connection points to the Kingdom of Khazaria. This was a wealthy and powerful kingdom that ruled the Caucasus, southern Russia, and parts of Turkey and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages. Historians credit the Khazars with checking the rapid Arab conquest, and preventing a Muslim takeover of Europe from the East. It is said that around 740 CE, King Bulan grew tired of his people’s backwards pagan beliefs and converted to Judaism. According to legend, he had invited representatives of the major faiths to argue their case, and concluded that Judaism was the true faith. (This is the basis of Rabbi Yehuda haLevi’s [c. 1075-1141] famous text, Kuzari.)

It is worth pointing out here that scholars have also recently pinpointed the Biblical Sefarad. There is now strong historical evidence to identify Sefarad with the ancient town of Sardis, also in Asia Minor (modern Turkey), of course. Sardis was known to the Lydians who inhabited it as Sfard, and to the Persians as Saparda. It goes without saying that

It is worth pointing out here that scholars have also recently pinpointed the Biblical Sefarad. There is now strong historical evidence to identify Sefarad with the ancient town of Sardis, also in Asia Minor (modern Turkey), of course. Sardis was known to the Lydians who inhabited it as Sfard, and to the Persians as Saparda. It goes without saying that