This week’s parasha, Toldot, begins with a focus on Isaac, now forty years old and finally married. Commenting on this, the Zohar says some incredible things. Embedded here in the Zohar is a deeply mystical text known as Midrash HaNe’elam, “the Hidden Midrash”. It is both an integral part of the Zohar (with others sections of it peppered throughout the Zohar’s many volumes) and a distinct work with its own flavour. It, too, dates back to the 2nd century CE teachings of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. Midrash HaNe’elam explains that Isaac was “brought back to life”, so to speak, by his wife Rebecca. How so? Continue reading

Tag Archives: Germany

The Origins of Ashkenazi Jews

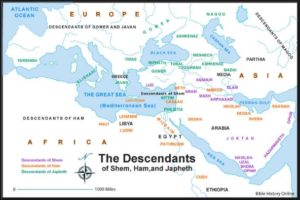

In this week’s parasha, Noach, we read about how the seventy primary descendants of Noah settled the Earth after the Great Flood. Noah had three sons, and it is often said that they divided the three continents of the Old World amongst them: Yefet (Japheth) got Europe, Shem got Asia, and Ham got Africa. This is not exactly accurate.

For one, Canaan is a son of Ham, but did not inhabit Africa, while Nimrod is said to be a son of Cush—also of Ham—yet we know Nimrod ruled Mesopotamia (Genesis 10:10). Another son of Ham is Mitzrayim, which is Egypt, yet Mitzrayim’s own children include Pathrusim and Caphtorim, names generally associated with Greek lands. (There is historical evidence to suggest that the early pre-Greek peoples did come from Egypt.) Yavan, the classic term for Greece, is a son of Yefet. As discussed in the past, Yavan is the same as Ionia, which is the western coast of Turkey, then inhabited by Greek-speaking peoples. (The famous city of Troy was in Ionia, in modern-day Turkey.)

In fact, essentially all of the seventy places inhabited by Noah’s descendants are places in modern Turkey or the Middle East. This makes sense, since the Torah was originally speaking to an audience that was unaware of most of Europe, the Far East, sub-Saharan Africa, and needless to say, the New World. The Torah mentions the origins of those territories that were familiar to the ancient Israelites, and that would have been their immediate neighbours. It also makes sense practically, since Noah got off the Ark in Ararat—probably somewhere in modern Turkey—and his children and grand-children would have settled lands that weren’t too far away from there.

Mt. Ararat, as seen from Yerevan, Armenia. It isn’t certain whether this Ararat is the Biblical Ararat.

One of Noah’s descendants is named Ashkenaz (Genesis 10:3). He is a grandson of Yefet, whose children all seem to have inhabited territories in Asia Minor and Armenia. Ashkenaz, too, is in that vicinity. Even in the time of the prophet Jeremiah centuries later, Ashkenaz was a kingdom in Turkey: “Raise a banner in the land, blow the shofar among the nations, prepare the nations against her, call together against her the kingdoms of Ararat, Minni, and Ashkenaz…” (Jeremiah 51:27) The prophet goes on to call on these and other powers in the area to come upon Babylon. Ashkenaz is one of the Turkish kingdoms bordering Babylon to the north, along with Ararat.

One of Noah’s descendants is named Ashkenaz (Genesis 10:3). He is a grandson of Yefet, whose children all seem to have inhabited territories in Asia Minor and Armenia. Ashkenaz, too, is in that vicinity. Even in the time of the prophet Jeremiah centuries later, Ashkenaz was a kingdom in Turkey: “Raise a banner in the land, blow the shofar among the nations, prepare the nations against her, call together against her the kingdoms of Ararat, Minni, and Ashkenaz…” (Jeremiah 51:27) The prophet goes on to call on these and other powers in the area to come upon Babylon. Ashkenaz is one of the Turkish kingdoms bordering Babylon to the north, along with Ararat.

Modern-day villages in Northeastern Turkey. (Credit: theconversation.com)

Amazingly, to this day ethnic Armenians in the region name Ashkenaz as one of their ancestors! This claim is not recent; the fifth-century Armenian scholar Koryun described the Armenians as an Askanazian people. Not surprisingly then, multiple places in Northeastern Turkey today still bear similar-sounding names, including the villages of Iskenaz, Eskenez, and Ashanas.

If Ashkenaz is a place in Turkey, how did it become associated with European Jews? Did Ashkenazi Jews come from Turkey?

Debunking Khazaria

One popular explanation for the Turkey-Ashkenaz connection points to the Kingdom of Khazaria. This was a wealthy and powerful kingdom that ruled the Caucasus, southern Russia, and parts of Turkey and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages. Historians credit the Khazars with checking the rapid Arab conquest, and preventing a Muslim takeover of Europe from the East. It is said that around 740 CE, King Bulan grew tired of his people’s backwards pagan beliefs and converted to Judaism. According to legend, he had invited representatives of the major faiths to argue their case, and concluded that Judaism was the true faith. (This is the basis of Rabbi Yehuda haLevi’s [c. 1075-1141] famous text, Kuzari.)

One popular explanation for the Turkey-Ashkenaz connection points to the Kingdom of Khazaria. This was a wealthy and powerful kingdom that ruled the Caucasus, southern Russia, and parts of Turkey and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages. Historians credit the Khazars with checking the rapid Arab conquest, and preventing a Muslim takeover of Europe from the East. It is said that around 740 CE, King Bulan grew tired of his people’s backwards pagan beliefs and converted to Judaism. According to legend, he had invited representatives of the major faiths to argue their case, and concluded that Judaism was the true faith. (This is the basis of Rabbi Yehuda haLevi’s [c. 1075-1141] famous text, Kuzari.)

Although Bulan did not impose his new religion on anyone, it is thought that much of his kingdom had become Jewish anyway within about a century. Remarkably, a large reserve of antique Khazar coins was found in Sweden in 1999, bearing the inscription “Moses is the Prophet of God”. (Modeled on, and sometimes just refashioned from, Arab coins saying that “Muhammad is the Prophet of Allah”!) Archaeologists have found similar Khazar coins all over the Old World, from England to China, showing the tremendous extent of Khazaria’s wealth and influence.

Khazar coin from c. 837 CE, with the inscription “Moses is the prophet of God”.

Like all kingdoms, Khazaria had an expiration date. It was eventually overrun by the Rus, Mongols, and others. Some say that many Jewish Khazar refugees migrated westward to Europe, and settled in the sparsely populated and resource-rich lands of Germany. Since they had come from a place traditionally known as Ashkenaz, they were labelled “Ashkenazi Jews”. This is a great story, but one that has far too many holes.

From a historical perspective, most scholars reject the Khazar hypothesis simply because there is little evidence that Khazaria experienced a mass conversion to Judaism. It is generally agreed that only a small portion of the Khazar nobility had converted, at best. Khazaria simply attracted many Jews to settle there since it was a rich kingdom with freedom of religion. In that case, any Jewish refugees that might later flee Khazaria to Europe would not be ethnic Khazars anyway.

The Schechter Letter

Then came a huge discovery from the Cairo Geniza. Now known as the Schechter Letter (as it was discovered by Solomon Schechter, 1847-1915), the text is a correspondence between a Khazari Jew and a Sephardi Jew, most likely Hasdai ibn Shaprut (c. 915-970 CE). The letter includes a brief history of Khazaria, and states that Khazaria’s Jews originally came from Persia and Armenia, from which they had fled persecution. One of their descendants, named Sabriel, eventually rose to Khazarian nobility, and finally became king. His wife, Serach, convinced him to go public with their Jewish heritage, and they did, inspiring others in the kingdom to convert to their new king’s religion.

The Schechter Letter confirms that the majority of the Jews in Khazaria were not actually Turkic converts but migrants from Persia and Armenia. Shortly after the letter was written, the Khazari Kingdom fell apart in 969 CE. (We know the letter must have been written after 941 CE, since it refers to a battle in that year for which we have other historical records.) The supposed Jewish exodus from Khazaria would have happened in the ensuing decades.

Yet, we read in the commentaries of French-born Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Itzchaki, 1040-1135) how he learned certain things from his visits to Jewish communities in neighbouring Ashkenaz (see, for example, Ketubot 77a), and that Ashkenaz is undoubtedly German (with Rashi occasionally using German/“Ashkenazi” words, as in Sukkah 17a, for instance). This implies that by Rashi’s time—less than a century after the fall of Khazaria—a geographical region in Western Europe referred to as “Ashkenaz” was already well-known, with Jews there freely conversing in German. It is unlikely that this would happen so soon after the fall of Khazaria; Ashkenaz must have existed long before.

Besides, we know that Jews already lived in Central Europe at the time of Charlemagne (742-814 CE), who had a good relationship with his Jewish subjects. Charlemagne was born right around the time King Bulan is supposed to have converted to Judaism, and before the rise of Sabriel (whom some identify with Bulan). This alone proves that Jews were already living in Europe long before any Khazari Jews appeared on the scene.

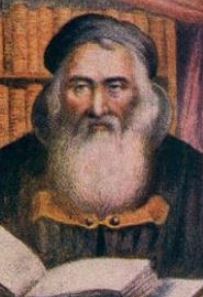

Among the Ashkenazi Jews of the Middle Ages themselves, the tradition was that they had been there since the destruction of the Second Temple. For example, the Rosh (Rabbi Asher ben Yechiel, c. 1250-1327) wrote in one of his responsa (20, 20) that when he moved to Toledo, Spain:

I would not eat according to [Sefardi] practice, adhering as I do to our own custom and to the tradition of our blessed forefathers, the sages of Ashkenaz, who received the Torah as an inheritance from their ancestors from the days of the destruction of the Temple. Likewise the tradition of our predecessors and teachers in France is superior…

A portrait identified with Rabbeinu Asher ben Yechiel, the “Rosh”

The Rosh speaks of three distinct European Jewish communities: Sefarad, Ashkenaz, and Tzarfat (France). This makes one wonder whether Rashi would have considered himself Ashkenazi (as people typically see him today) or Tzarfati? Rashi was born and died in Troyes, France, though he spent time in Worms and Mainz in Germany, hence the reference above to his having learned things while visiting “Ashkenaz”. This implies that Rashi may not have considered himself Ashkenazi at all. (His father was called Rabbi Itzchak haTzarfati, and though he lived for a time in Worms, probably hailed from Lunel in Southern France.) Whatever the case, we see that the Sefardi, Ashkenazi, and Tzarfati Jewish communities were already firmly entrenched at the time of Khazaria’s fall.

Delving into Ashkenazi Genes

Science can shed further light on Ashkenazi origins. One study of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA, which is passed strictly from mother to child) found that some 40% of Ashkenazi Jews come from a group of mothers in Europe, possibly converts, approximately 2000 years ago (another related study here). This would have been around the destruction of the Second Temple. We know that many Jews fled Judea (or were expelled) at the time, and settled across the Roman Empire and beyond. Similarly, a study of Y chromosomes (passed strictly from father to son) shows that most Ashkenazi Levites have a common ancestor who lived at least 1500 years ago, most likely in the Middle East or already having migrated to Europe. These scientists conclude that the Khazar hypothesis is “highly unlikely”.

Other genetic studies do appear to show high degrees of relatedness between Turkic and Iranian peoples with Ashkenazi Jews, especially males. Of course, Jews have lived and migrated just about everywhere, and undoubtedly mixed with local populations, while drawing numerous converts. One interesting study found that about 5% of Ashkenazi males are part of the Q3 haplogroup, part of the wider Q group which represents Native Americans and Asians. The researchers concluded that Q3 entered the Jewish gene pool sometime in the 1st millennium. Some say this is due to the Ashina Turks (among the Khazar elite) who converted to Judaism and took Jewish wives. Either way, it is only a tiny minority of Ashkenazis that carry such genes.*

What we see from genetic studies is that most Ashkenazi Jews today descend from ancestors that were already in Europe long before the rise of the Khazars. Historical evidence confirms the existence of widespread Jewish communities in Europe before the time of Khazaria, too. In reality, the Khazar hypothesis keeps being resurrected because it is a convenient tool for anti-Semites to attack modern Jews as “imposters” (meanwhile completely forgetting the other half of the world’s Jews which are not Ashkenazi at all!) or for anti-Zionists to deny a Jewish connection to the land of Israel.

Having said all that, we must still answer the key question: where did the “Ashkenazi” label come from?

Adapting Names

When we look at the seventy “original” nations—descendants of Noah—we find that they represent a very small geographical area. Of the seventy, fourteen come from Yefet and represent Asia Minor, Armenia, and the Aegean islands (Genesis 10:5), nine are Cushites (presumably dark-skinned people), eight of Mitzrayim, twelve are Canaanites, and twenty-six are Middle Eastern, or possibly even just Mesopotamian. As already mentioned, the Torah’s narratives are confined to a narrow geographical space that was relevant to the ancient Israelites.

A “Table of Nations” from the ArtScroll Stone Chumash

When Jews started migrating out of Israel and beyond the Middle East, they needed to come up with names for these new territories they inhabited. So, they adapted the Biblical place-names of locations that no longer existed or whose identity was no longer known. For example, Sefarad became Spain and Tzarfat became France. When scripture speaks of Sefarad or Tzarfat (as in Ovadiah 1:20), it is certainly not speaking of Spain or France! For instance, the prophet Elijah went to Tzarfat, which is described as being next to Sidon (I Kings 17:9). Sidon is, of course, a well-known ancient city, in what is now Lebanon.

For the first Jews who settled in Spain and France, they had migrated the farthest West they could possibly go at the time. For them, these new lands were the most distant from Jerusalem, so they fittingly adapted terms for places described as being exceedingly far from the Holy Land (as in Ovadiah 1:20). They couldn’t use the names of places that were still extant, but only those ancient names that were no longer relevant. In the same fashion they described Germany as “Ashkenaz”, while Bohemia was surprisingly called “Canaan”. Therefore, to say that Ashkenazi Jews are Turkish because Ashkenaz was originally a place in Turkey is like saying French Tzarfati Jews are Lebanese because Tzarfat was originally a place in Lebanon!

It is worth pointing out here that scholars have also recently pinpointed the Biblical Sefarad. There is now strong historical evidence to identify Sefarad with the ancient town of Sardis, also in Asia Minor (modern Turkey), of course. Sardis was known to the Lydians who inhabited it as Sfard, and to the Persians as Saparda. It goes without saying that Sephardic Jewish origins have nothing to do with Turks, as don’t the origins of Lydians (probably the “Ludim” of Genesis 10:13, or the Lud of Genesis 10:22), nor the Yavanim, the Greek Ionians, all of whom inhabited that same area of Asia Minor.

It is worth pointing out here that scholars have also recently pinpointed the Biblical Sefarad. There is now strong historical evidence to identify Sefarad with the ancient town of Sardis, also in Asia Minor (modern Turkey), of course. Sardis was known to the Lydians who inhabited it as Sfard, and to the Persians as Saparda. It goes without saying that Sephardic Jewish origins have nothing to do with Turks, as don’t the origins of Lydians (probably the “Ludim” of Genesis 10:13, or the Lud of Genesis 10:22), nor the Yavanim, the Greek Ionians, all of whom inhabited that same area of Asia Minor.

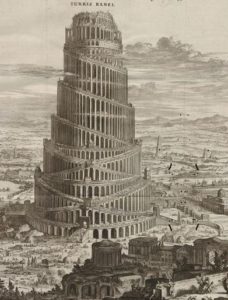

The Tower of Babel

‘Turris Babel’ by Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680)

After telling us the divisions of the nations in Genesis 10, the Torah goes on to relate the narrative of Migdal Bavel. We are told that the people were all still unified at this point, speaking one tongue. They gathered in Babylon to build a tower to the Heavens, with nefarious intentions. Their plans were thwarted by God, who then scattered the people all over the world and confounded their tongues.

From a mystical perspective, at this point those seventy root nations—which originally inhabited Asia Minor and the Middle East—were spread all around the globe into a multitude of various peoples with new cultures and languages. Thus, all of the world’s thousands of nations and ethnicities, wherever they may be, are spiritually rooted in one of Noah’s seventy descendants.

Consequently, there were those who believed that Ashkenaz was dispersed to Central Europe. What’s amazing is that this was not only a Jewish belief, but a Christian one, too. The evangelical Christian pastor Ray Stedman (1917-1992) wrote:

The oldest son of Gomer was Ashkenaz. He and his descendants first settled around the Black Sea and then moved north into a land which is called Ascenia, and which later became known as the Islands of Scandia, which we now know as Scandinavia. You can trace a direct link between Ashkenaz and Scandinavia.

Basing himself on earlier sources, he lists Ashkenaz as referring to all Saxons, Scandinavians, and Germanic tribes. This argument was made at least as far back as the 4th century (long before the Khazars appeared on the scene), in Eusebius’ Historia Eccliesiastica, where Ashkenaz is Scanzia, another name for Scandinavia and/or Saxony.

Around that same time, the Talmud (Yoma 10a) identifies Gomer (the father of Ashkenaz) with Germamia. While this Germamia is possibly referring to Cimmeria, or Germanikia in Syria—which would have been more familiar to the Babylonian Sages living in the Persian Empire—it is very likely that Jews who settled in Germany would see Germamia as referring to their new land. Combined with the alliteration between “Ashkenaz” and “Saxony”/“Scanzia”, we can understand why the Jews that settled in Germany adapted the name Ashkenaz.

As an intriguing aside, the Talmud cited above holds that Yefet is a forefather of the Persians, too. The Talmud reads: “How do we know that the Persians are derived from Yefet? Because it is written: ‘The sons of Yefet: Gomer, and Magog… and Tiras’” The Sages say Tiras is Paras, Persia. Intriguingly, the Sages seem to connect Magog (of “Gog u’Magog” fame) with the Persians. That might make alarm bells go off in the heads of modern readers who see Iran as playing a central role in an End of Days armagaddeon.

To conclude, the hypothesis that Ashkenazi Jews originate among Turkish converts is completely false. While some Turkish converts certainly joined the Jewish nation in the Middle Ages, Ashkenazi Judaism predates this phenomenon by centuries. Both historical evidence and genetic analyses confirm a European Jewish presence as far back as 2000 years ago.

*Shortly after publishing this article, Kevin Brook pointed out the following to me, from his book The Jews of Khazaria (pg. 204):

Some researchers thought it was possible that these could have been inherited from the Khazars, but this idea is no longer viable. Ashkenazim belong to the Q haplogroups that were later precisely identified as Q-Y2200 (Q1b1a1a1a) and Q-YP1035 (Q1b1a1a1a2a2). On the Y chromosome tree, Q-Y2200’s parent haplogroup Q-Y2225 (Q1b1a1a1) was found in an Italian sample from Sicily, and geneticists determined that QY2225’s distant ancestors had apparently lived in the Middle East. The Ashkenazic branches of Q are very different from Q1a1b-M25 and Q1a2-M346, which are common among Turkic-speaking peoples, and the common ancestor between them all lived many thousands of years ago, far in advance of Khazaria’s existence.

The above essay is adapted from Garments of Light, Volume Three.

Get the book here!

The Mystical Meaning of Exile and Terrorism

This week we read the parasha of Bechukotai, famous for its list of blessings, and curses, should Israel faithfully follow God’s law, or not. In Leviticus 26:33, God warns that “I will scatter you among the nations, and I will draw out the sword after you; and your land shall be a desolation, and your cities shall be a waste.” These prophetic words have, of course, come true in Jewish history. Israel has indeed been exiled to the four corners of the world, and experienced just about every kind of persecution. Yet, within every curse there is a hidden blessing.

‘The Flight of the Prisoners’ by James Tissot, depicting the Jewish people being exiled to Babylon.

The Talmud (Pesachim 87b) states that the deeper purpose of exile is for the Jews to spread Godliness to the rest of the world. After all, our very mandate was to be a “light unto the nations” (Isaiah 42:6) and to spread knowledge of Hashem and His Torah. How could we ever accomplish this if we were always isolated in the Holy Land? It was absolutely necessary for Israel to be spread all over the globe in order to introduce people to Hashem, to be a model of righteousness, and to fulfil the various spiritual rectifications necessary to repair this broken world.

The Arizal explains that by praying, reciting blessings, and fulfilling mitzvot, a Jew frees the spiritual sparks trapped within the kelipot, literally “husks”. This idea hearkens back to the concept of Shevirat haKelim, the “Shattering of the Vessels”. The Arizal taught that God initially crafted an entirely perfect universe. Unfortunately, this world couldn’t contain itself and shattered into a multitude of pieces, spiritual “sparks” trapped in this material reality. While God had rebuilt most of the universe, He left it to Adam and Eve to complete the rectification through their own free will. They, too, could not affect that tikkun, and the cosmos shattered yet again. The process repeated itself on a number of occasions, the last major one being at the time of the Golden Calf.

Nonetheless, with each passing phase in history, more and more of those lost, trapped sparks are rediscovered and restored to their rightful place. The mystical mission of every Jew is to free those sparks wherever they go. The Arizal speaks of this at great length, and it permeates every part of his teachings. Eating, for example, serves the purpose of freeing sparks trapped within food—which is why it is so important to consume only kosher food, and to carefully recite blessings (which are nothing but fine-tuned formulas for spiritual rectification) before and after. The same is true with every mitzvah that we do, and every prayer we recite.

Thus, while exile is certainly difficult and unpleasant, it serves an absolutely vital spiritual purpose. This is why the Midrash states that exile is one of four things God created regretfully (Yalkut Shimoni on Isaiah, passage 424). It is why God already prophesied that we would be exiled—even though we hadn’t yet earned such a punishment! And it is why God also guaranteed that we would one day return to our Promised Land, as we have miraculously begun to do in recent decades.

Four, Five, or Eight Exiles?

In Jewish tradition, it is said that there are four major exiles: the Babylonian, the Persian, the Greek, and the Roman. We are still considered to be within the “Roman” or Edomite (European/Christian) exile. Indeed, the Roman Empire never really ended, and just morphed from one phase into another, from the Byzantine Empire to the Holy Roman Empire, and so forth.

Babylonian Shedu

This idea of four exiles originated with Daniel’s vision of four great beasts (Daniel 7:3-7). The first was a lion with eagle wings—a well-known symbol of ancient Babylon. Then came a fierce bear, an animal which the Talmud always likens to the Persians. The swift leopard represents the Greeks that conquered the known world in lightning speed under Alexander the Great. The final and most devastating beast is unidentified, representing the longest and cruelest exile of Edom.

The Midrash states that Jacob himself foresaw these exiles in his vision of the ladder (Genesis 28). There he saw four angels, each going up a number of rungs on the ladder equal to the number of years Israel would be oppressed by that particular nation. The last angel continued to climb ever higher, with Jacob unable to see its conclusion, alluding to the current seemingly never-ending exile. The big question is: why are these considered the four exiles. Haven’t the Jewish people been exiled all around the world? Have we not been oppressed by other nations besides these?

The Arizal explains (Sha’ar HaMitzvot on Re’eh) that while Jews have indeed been exiled among all seventy root nations, it is only in these four that all Jews were exiled in. Yet, he maintains that any place where even a single Jew has been exiled is considered as if the entire nation was exiled there. The Arizal further explains that these four exiles were already alluded to in Genesis 2:10-14, where the Torah describes the four rivers that emerged from Eden. Each river corresponds to one exile. The head river of Eden that gives rise to the other four corresponds to the very first exile of the Jews, the exile within which the Jewish people were forged: Egypt, the mother of all exiles.

Elsewhere, the Arizal adds that there is actually a fifth exile, that of Ishmael (Etz Ha’Da’at Tov, ch. 62). History makes this plainly evident, of course, as the Jewish people have suffered immensely under Arab and Muslim oppression to this very day. The idea of Ishmael being the final exile was known long before the Arizal, and is mentioned by earlier authorities. In fact, one tradition holds that each exile has two components:

We know that before the Babylonians came to destroy the Kingdom of Judah and its capital Jerusalem, the Assyrians had destroyed the northern Kingdom of Israel with the majority of the Twelve Tribes. We also know that the Persians were united with the Medians. Technically speaking, Alexander the Great was not a mainstream Greek, but a Macedonian. While he was the one who conquered Israel, his treatment of the Jews was mostly fair. It was only long after that the Seleucid Greeks in Syria really tried to extinguish the Jews. Thus, the doublets are Assyria-Babylon (Ashur-Bavel), Persia-Media (Paras-Madai), Macedon-Greece (Mokdon-Yavan), with the final doublet being Edom-Ishmael. The latter has a clear proof-text in the Torah itself, where we read how Esau (ie. Edom) married a daughter of Ishmael (Genesis 28:9). The Sages suggest that this is an allusion to the joint union between Edom and Ishmael to oppress Israel in its final exile.

The Arizal certainly knew the above, so why does he speak of a fifth exile under Ishmael, as well as a fifth (original) exile under Egypt?

The End is Wedged in the Beginning

One of the most well-known principles in Kabbalah is that “the end is wedged in the beginning, and the beginning in the end”. What the Arizal may have been hinting at is that the final Ishmaelite exile is a reflection of the original Egyptian exile. Indeed, the Arizal often speaks of how the final generation at the End of Days is a reincarnation of the Exodus generation. (According to one tradition, there were 15 million Jews in ancient Egypt, just as there are roughly 15 million in the world today.) The first redeemer Moses took us out of the Egyptian exile, and we await Moses’ successor, the final redeemer Mashiach, to free us from the Ishmaelite exile.

In highly symbolic fashion, the land of ancient Egypt is currently occupied by Muslim Arabs. The Ishmaelites have quite literally taken the place of ancient Egypt. Come to think of it, the lands of all the four traditional nations of exile are now Ishmaelite: Bavel is Iraq, Paras is Iran, Seleucid Greece is Syria, and the Biblical land of Edom overlaps Jordan. The four rivers of Eden would have run through these very territories. It is quite ironic that Saddam Hussein openly spoke of himself as a reincarnated Nebuchadnezzar, seeking to restore a modern-day Babylonian Empire. Meanwhile, each day in the news we hear of the looming Syria-Iran threat. Just as Egypt was the mother of all four “beasts”, it appears that the four beasts converge under a new Ishmaelite banner for one final End of Days confrontation.

There is one distinction however. In the ancient land of Egypt, all Jews were physically trapped. We do not see this at all today, where very few Jews remain living in Muslim states. Nonetheless, every single Jew around the world, wherever they may be, is living under an Ishmaelite threat. Muslims in France, for example, have persistently attacked innocent Jews in horrific acts—so much so that recently 250 French intellectuals, politicians, and even former presidents banded together to demand action against this absurd violence and anti-Semitism. Similar acts of evil have taken place all over the world. This has been greatly exacerbated by the recent influx of Muslim refugees to the West, as admitted by Germany’s chancellor Angel Merkel who recently stated: “We have refugees now… or people of Arab origin, who bring a different type of anti-Semitism into the country…”

In 2017, Swedish police admitted that there are at least 23 “no-go” Sharia Law zones in their country.

It is important to note that when Scripture speaks of the End of Days, it is not describing a regional conflict, but an international one. The House of Ishmael is not a local threat to Israel alone, or only to Jewish communities, but to the entire globe. Every continent has felt the wrath of Islamist terrorism, and whole communities in England, France, and even America have become cordoned off as “sharia law” zones. Ishmael is even a threat to himself. Muslims kill each other far more than they kill non-Muslims. In 2011, the National Counter-Terrorism Center reported that between 82% and 97% of all Islamist terror victims are actually Muslim. All but three civil wars between 2011 and 2014 were in Muslim countries, and all six civil wars that raged in 2012 were in Muslim countries. In 2013, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom showed that 10 of the 15 most intolerant and oppressive states in the world were Muslim ones.

The Torah wasn’t wrong when it prophesied (Genesis 16:12) that Ishmael would be a “wild man; his hand against every man, and every man’s hand against him, and upon all of his brothers he will dwell.” Every Jew—and every human being for that matter—is experiencing an Ishmaelite exile at present.

The Exile Within

There is one more way of looking at the four exiles: not as specific nations under whom we were once oppressed, but as four oppressive forces that have always constrained Israel, and continue to do so today. These are the four root issues plaguing the Jews, and keeping us in “exile” mode.

The first is Edom, that spirit of materialism and physicality embodied by Esau. Unfortunately, such greed and gluttony has infiltrated just about every Jewish community, including those that see themselves as the most spiritual. The second, Bavel, literally means “confusion”, that inexplicable madness within the Jewish nation; the incessant infighting, the divisiveness, and the sinat chinam. Yavan is Hellenism, or secularism. In Hebrew, the word for a secular Jew is hiloni, literally a “Hellene”. Just as this week’s parasha clearly elucidates, abandoning the Torah is a root cause of many ills that befall the Jews. Finally, there is Paras. It was because the Jews had assimilated in ancient Persia that the events of Purim came about. Paras represents that persistent problem of assimilation.

It is important to point out that assimilation is different from secularism. There are plenty of secular Jews that are also very proud Jews. They openly sport a magen David around their neck, worry every day about Israel, want their kids to marry only other Jews, and though they don’t want to be religious, still try to connect to their heritage, language, and traditions. The assimilated Jew is not that secular Jew, but the one that no longer cares about their Jewish identity. It is the Jew that entirely leaves the fold. Sometimes, it is the one that becomes a “self-hating” Jew, or converts to another religion. Such Jews have been particularly devastating to the nation, and often caused tremendous grief. Some of the worst Spanish inquisitors were Jewish converts to Catholicism. Karl Marx and the Soviet Communists that followed are more recent tragedies. Not only do they leave their own people behind, they bring untold suffering to their former compatriots.

While there may be literal Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, and Edomites out there, the bigger problem for the Jewish people is the spiritual Bavel, Paras, Yavan, and Edom that infects the hearts and minds of the nation: infighting, assimilation, secularism, materialism. It is these issues that we should be spending the most time meditating upon, and expending the most effort to solve. Only when we put these problems behind us can we expect to see the long-awaited end to exile.