As we prepare to usher in another new year, we pray fervently that it will be the one in which we finally see the completion of the Geulah, the great redemption of our people, followed by the transformation of the entire world into a more wholesome, peaceful, and divine place. As we listen to the shofar on Rosh Hashanah, we hope it will be the great shofar that will herald the coming of Mashiach (Isaiah 27:13). We hope that it will be the final Judgement Day, and that we will all be inscribed in the Book of Life for good. But as we yearn for these things, it is vital to ask: what are we doing practically to bring about that reality? There are so many issues and threats confronting us both externally and internally. And we know that, at the end of day, all of these things come not from various political opponents, or antisemites, or military powers, or terrorists, or propagandists—but straight from Hashem.

God tells us over and over again in the Torah that if we follow his mitzvot properly then we will be safe, blessed, and prosperous. It’s only when we don’t that all the suffering and travails come upon us. So, as a nation, we are obviously doing something wrong here. Yes, as we all know, we are lacking unity. There is a lot of disagreement and infighting, and many within the house of Israel remain secular and disconnected. But we rarely ask why this is the case, and what we can actually do to fix it. It’s like we’ve helplessly accepted the status quo, as if there’s nothing we can do about it. When our Sages list all the things wrong with the world before Mashiach comes (Sotah 49b), they conclude by saying “there is no one to rely on except our Father in Heaven”. Some of our rabbis understood this concluding statement as being part of the list of things wrong with the world, ie. that people have given up and say there is nothing we can do but wait for Hashem!

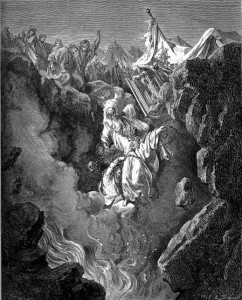

The truth is that God is waiting for us. This was precisely the case at the Splitting of the Sea, when Moses prayed fervently to Hashem and Hashem replied: ma titzak alai?! “Why are you calling out to Me?!” (Exodus 14:15) It was Nachshon who understood what had to be done, and when everyone else stood back passively; crying, stressing, waiting; he decided to dive into the water. Only then did the Sea split. Today we are, yet again, at another splitting of the sea moment, right at the finish line of Geulah, and we all need to be Nachshon right now. So, what can we do? How do we actually solve the lack of unity? How do we address the widespread secularism and materialism? How do we bring people back to Hashem, back to Torah and mitzvot, to a “Geulah mindset”? How do we shift away from passively waiting to actively doing? In short, how do we bring Mashiach? Continue reading