An illustration of Rabbi Akiva from the Mantua Haggadah of 1568

This week we continue to celebrate Passover and count the days of the Omer. The 49-day counting period is meant to prepare us spiritually for Shavuot, for the great day of the Giving of the Torah. As our Sages teach, the Torah wasn’t just given once three millennia ago, but is continually re-gifted each year, with new insights opening up that were heretofore never possible to uncover. At the same time, the Omer is also associated with mourning, for in this time period the 24,000 students of Rabbi Akiva perished, as the Talmud (Yevamot 62b) records:

Rabbi Akiva had twelve thousand pairs of disciples, from Gabbatha to Antipatris, and all of them died at the same time because they did not treat each other with respect. The world remained desolate until Rabbi Akiva came to our Masters in the South and taught the Torah to them. These were Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Yehudah, Rabbi Yose, Rabbi Shimon, and Rabbi Elazar ben Shammua—and it was they who revived the Torah at that time. A Tanna taught: All of them died between Pesach and Shavuot.

Rabbi Akiva is a monumental figure in Judaism. People generally don’t appreciate how much we owe to Rabbi Akiva, and how much he transformed our faith. In many ways, he established Judaism as we know it, during those difficult days following the destruction of the Second Temple, until the Bar Kochva Revolt, in the aftermath of which he was killed.

Rabbi Akiva is by far the most important figure in the development of the Talmud. From various sources, we learn that it was he who first organized the Oral Torah of Judaism into the Six Orders that we have today. The Mishnah, which is really the first complete book of Jewish law and serves as the foundation for the Talmud, was possibly first composed by Rabbi Akiva. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 86a) states that the main corpus of the Mishnah (including any anonymous teaching) comes from Rabbi Meir, while the Tosefta comes from Rabbi Nehemiah, the Sifra from Rabbi Yehuda, and the Sifre from Rabbi Shimon—and all are based on the work of Rabbi Akiva. Indeed, each of these rabbis was a direct student of Rabbi Akiva. (Although Rabbi Nehemiah is not listed among the five students of Rabbi Akiva in the Talmudic passage above, he is on the list in Sanhedrin 14a.)

In short, Rabbi Akiva began the process of formally laying down the Oral Tradition, which resulted in the production of the Mishnah a generation later, and culminated in the completion of the Talmud after several centuries.

It wasn’t just the Oral Torah that Rabbi Akiva had a huge impact on. We learn in the Talmud (Megillah 7a) that Rabbi Akiva was involved in a debate regarding which of the books of the Tanakh is holy and should be included in the official canon. Although it was the Anshei Knesset HaGedolah (“Men of the Great Assembly”) who are credited with first compiling the holy texts that make up the Tanakh, the process of canonization wasn’t quite complete until the time of Rabbi Akiva. Therefore, Rabbi Akiva both “completed” the Tanakh and “launched” the Talmud. This may just make him the most important rabbi ever.

That distinction is further reinforced when we consider the time period that Rabbi Akiva lived in. On the one hand, he had to contend with the destruction wrought by the Romans, who sought to exterminate Judaism for good. They made Torah study and Torah teaching illegal, and executed anyone who trained new rabbis. In fact, Rabbi Akiva was never able to ordain his five new students after his original 24,000 were killed. He taught them, but lost his life before the ordination could take place. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 14a) records:

The Evil Government [ie. Rome] decreed that whoever performed an ordination should be put to death, and whoever received ordination should be put to death, and the city in which the ordination took place should be demolished, and the boundaries wherein it had been performed, uprooted.

What did Rabbi Yehudah ben Bava do? He went and sat between two great mountains, between two large cities; between the Sabbath boundaries of the cities of Usha and Shefaram, and there ordained five sages: Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Yehudah, Rabbi Shimon, Rabbi Yose, and Rabbi Elazar ben Shammua. Rabbi Avia also adds Rabbi Nehemiah to the list.

As soon as their enemies discovered them, Rabbi Yehudah ben Bava urged them: “My children, flee!” They said to him: “What will become of you, Rabbi?” He replied: “I will lie down before them like a stone which none can overturn.” It was said that the enemy did not stir from the spot until they had driven three hundred iron spears into his body, making it like a sieve…

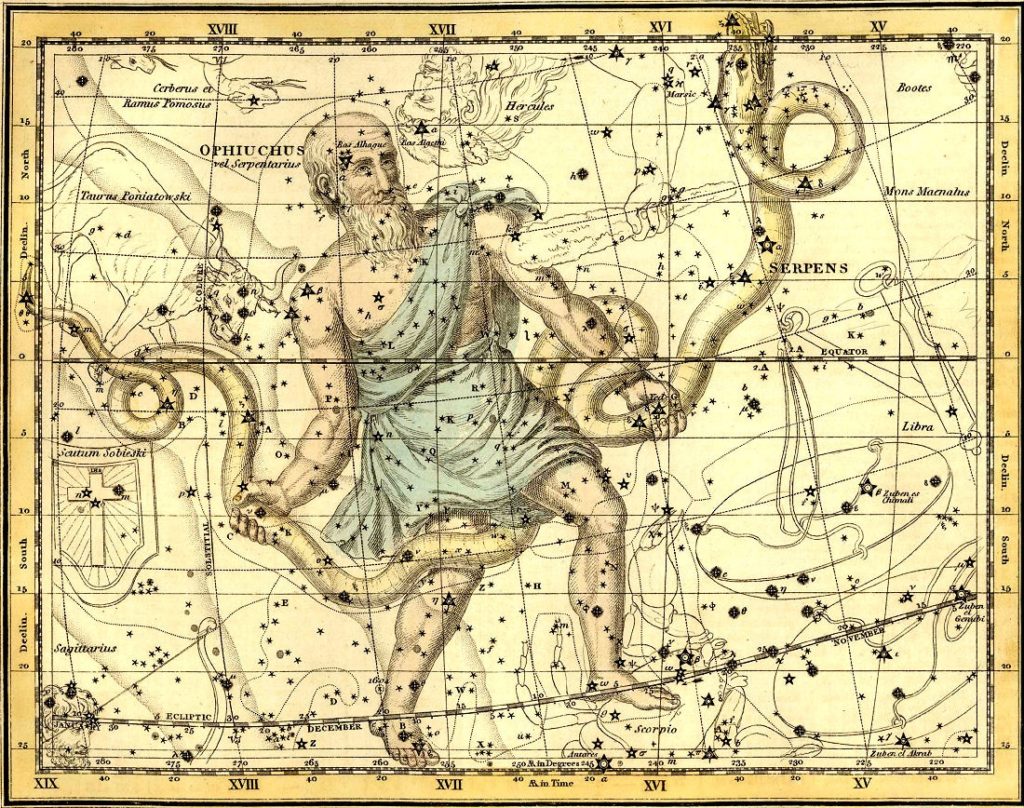

An illustration of Rabbis Akiva, Elazar ben Azaria, Tarfon, Eliezer, and Yehoshua, as they sit in Bnei Brak on Passover discussing the Exodus all night long, as described in the Passover Haggadah. Some say what they were actually discussing all night is whether to support the Bar Kochva Rebellion against Rome. In the morning, their students came to ask for their decision. They answered: “shfoch hamatcha el hagoyim asher lo yeda’ucha…” as we say when we pour the fifth cup at the Seder.

In the wake of the catastrophic destruction of the Bar Kochva Revolt, and the unbearable decrees of the Romans, traditional Judaism and its holy wisdom nearly vanished. The “world was desolate”, as the Talmud describes, “until Rabbi Akiva came” and relayed that holy wisdom to the five students who would ensure the survival of the Torah. In fact, the vast majority of the Mishnah’s teachings are said in the name of either Rabbi Akiva or these five students. Rabbi Yehudah bar Ilai alone is mentioned over 600 times in the Mishnah—way more than anyone else—followed by Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Shimon, and Rabbi Yose. Without Rabbi Akiva’s genius and bravery, Judaism may have been extinguished.

Meanwhile, Judaism at the time also had to contend with the rise of Christianity. Rabbi Akiva had to show Jews the truth of the Torah, and protect them from the sway of Christian missionaries. It is generally agreed that Onkelos (or Aquila of Sinope) was also a student of Rabbi Akiva. Recall that Onkelos was a Roman who converted to Judaism, and went on to make an official translation of the Torah for the average Jew. That translation, Targum Onkelos, is still regularly read today. What is less known is that Onkelos produced both a Greek and Aramaic translation of the Torah to make the holy text more accessible to Jews (as Greek and Aramaic were the main vernacular languages of Jews at the time). Every Jew could see for himself what the Torah really says, and would have the tools necessary to respond to missionaries who often mistranslated verses and interpreted them to fit their false beliefs.

Interestingly, some scholars have pointed out that Rabbi Akiva may have instituted Mishnah and began its recording into written form as a way to help counter Christianity. Because Christians adopted the Torah and appropriated the Bible as their own, it was no longer something just for Jews. As such, it was no longer enough for Jews to focus solely on Tanakh, for Christians were studying it, too, and the study of Tanakh was no longer a defining feature of a Jew either. The Jewish people therefore needed another body of text to distinguish them from Christians, and the Mishnah (and later, Talmud) filled that important role. This may be a further way in which Rabbi Akiva preserved Judaism in the face of great adversity.

Finally, Rabbi Akiva also preserved and relayed the secrets of the Torah. He was the master Kabbalist, the only one who was able to enter Pardes and “exit in peace” (Chagigah 14b). One of his five students was Rabbi Shimon, yes that Rabbi Shimon: Shimon bar Yochai, the hero of the Zohar. Thus, the entire Jewish mystical tradition was housed in Rabbi Akiva. Without him, there would be no Zohar, no Ramak or Arizal, nor any Chassidut for that matter.

All in all, Rabbi Akiva is among the most formidable figures in Jewish history. In some ways, he rivals only Moses.

How Moses Returned in Rabbi Akiva

We see a number of remarkable parallels in the lives of Moses and Rabbi Akiva. According to tradition, Rabbi Akiva also lived to the age of 120, like Moses. We also know that Rabbi Akiva was an unlearned shepherd for the first third of his life. At age 40, he went to study Torah for twenty-four years straight and became a renowned sage. According to the Arizal, Rabbi Akiva carried a part of Moses’ soul, which is why their lives parallel so closely (Sha’ar HaGilgulim, ch. 36):

Moses spent the first forty years of his life in the palace of Pharaoh, ignorant of Torah, just as Rabbi Akiva spent his first forty without Torah. The next forty years Moses spent in Cush and Midian, until returning to Egypt as the Redeemer of Israel at age 80, and leading the people for the last forty years of his life. Rabbi Akiva, too, became the leading sage of Israel at age 80, and spent his last forty years as Israel’s shepherd. As we’ve seen above, it isn’t a stretch to say that Rabbi Akiva “redeemed” Israel in his own way.

More specific details of their lives are similar as well. Moses’ critical flaw was in striking the rock to draw out water from it. With Rabbi Akiva, the moment that made him realize he could begin learning Torah despite his advanced age was when he saw a rock with a hole in it formed by the constant drip of water. He reasoned that if soft water can make a permanent impression on hard stone, than certainly the Torah could make a mark on his heart (Avot d’Rabbi Natan 6:2). Perhaps this life-changing encounter of Rabbi Akiva with the rock and water was a tikkun of some sort for Moses’ error with the rock and water.

Similarly, we read in the Torah how 24,000 men of the tribe of Shimon were killed in a plague under Moses’ watch (Numbers 25:9). This was a punishment for their sin with the Midianite women. Moses stood paralyzed when this happened, unsure of how to deal with the situation. The plague (and the sin) ended when Pinchas took matters into his own hands, and was blessed with a “covenant of peace”. The death of the 24,000 in the time of Moses resembles the 24,000 students of Rabbi Akiva that perished, with Rabbi Akiva, like Moses, unable to prevent their deaths. In fact, Kabbalistic sources say that the 24,000 students of Rabbi Akiva were reincarnations of the 24,000 men of Shimon (see Sefer Gilgulei Neshamot, Letter Kaf).

There is at least one more intriguing parallel between Moses and Rabbi Akiva. We know that the adult generation in the time of Moses was condemned to die in the Wilderness because of the Sin of the Spies. Yet, we see that some people did survive and enter the Promised Land. The Torah tells us explicitly that Joshua and Caleb, the good spies, were spared the decree. In addition, Pinchas was blessed with a long life (for his actions with the plague of the 24,000) and survived to settle in Israel. (According to tradition, Pinchas became Eliyahu, who never died but was taken up to Heaven in a flaming chariot.) We also read in the Book of Joshua that Elazar, the son and successor of Aaron, continued to serve as High Priest into the settlement of Israel, and passed away around the same time as Joshua (Joshua 24:33). Finally, the Sages teach that the prophet Ahiyah HaShiloni was born in Egypt and “saw Amram” (the father of Moses) and lived until the times of Eliyahu, having been blessed with an incredibly long life (Bava Batra 121b). In his introduction to the Mishneh Torah, the Rambam (Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, 1135-1204) lists Ahiyah as a disciple of Moses, later a member of David’s court, and the one who passed on the tradition through to the time of Eliyahu.

Altogether, there are five people who were born in the Exodus generation but were spared the decree of dying in the Wilderness. (Note: the Sages do speak of some other ancient people who experienced the Exodus and settled in Israel, including Serach bat Asher and Yair ben Menashe, but these people were born long before the Exodus, in the time of Jacob and his sons.) These five people were also known to be students of Moses. The conclusion we may come to is that five of Moses’ students survived to bring the people and the Torah into Israel, just as five of Rabbi Akiva’s students survived to keep alive the Torah and Israel.

If we look a little closer, we’ll find some notable links between these groups of students. We know that Elazar ben Shammua, the student of Rabbi Akiva, was also a kohen, like Elazar the Priest. Caleb and Joshua are descendants of Yehudah and Yosef, reminiscent of Rabbi Yehudah and Rabbi Yose (whose name is short for “Yosef”), the students of Rabbi Akiva. Rabbi Meir, often identified with the miracle-worker Meir Baal HaNess, has much in common with Pinchas/Eliyahu, while Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai explicitly compared himself to Ahiyah haShiloni in the Midrash (Beresheet Rabbah 35:2). As such, there may be a deeper connection lurking between the five surviving students of Moses and the five surviving students of Rabbi Akiva.

Lastly, we shouldn’t forget the Talmudic passage that describes how Moses visited the future classroom of Rabbi Akiva, and was amazed at the breadth of wisdom of the future sage. Moses asked God why He didn’t just choose Akiva to give the Torah to Israel? It was such a great question that God didn’t reply to Moses!

The Greatest Torah Principles

Of all the vast oceans of wisdom that Rabbi Akiva taught and relayed, what were the most important teachings he wished everyone to take to heart? First and foremost, Rabbi Akiva taught that the “greatest Torah principle” (klal gadol baTorah) is to love your fellow as yourself (see Sifra on Kedoshim). Aside from this, he left several gems in Pirkei Avot (3:13-16), which is customary to read now between the holidays of Pesach and Shavuot:

Rabbi Akiva would say: excessive joking and light-headedness accustom a person to promiscuity. Tradition is a safety fence for Torah, tithing is a safety fence for wealth, vows a safety fence for abstinence; a safety fence for wisdom is silence.

He would also say: Beloved is man, for he was created in the image [of God]; it is a sign of even greater love that it has been made known to him that he was created in that image, as it says, “For in the image of God, He made man” [Genesis 9:6]. Beloved are Israel, for they are called children of God; it is a sign of even greater love that it has been made known to them that they are called children of God, as it is stated: “You are children of the Lord, your God” [Deuteronomy 14:1]. Beloved are Israel, for they were given a precious item [the Torah]; it is a sign of even greater love that it has been made known to them that they were given a precious item, as it is stated: “I have given you a good portion—My Torah, do not forsake it” [Proverbs 4:2].

All is foreseen, yet freedom of choice is granted. The world is judged with goodness, and all is in accordance with the majority of one’s deeds.

He would also say: Everything is given as collateral, and a net is spread over all the living. The store is open, the storekeeper extends credit, the account-book lies open, the hand writes, and all who wish to borrow may come and borrow. The collection-officers make their rounds every day and exact payment from man, with his knowledge and without his knowledge. Their case is well-founded, the judgement is a judgement of truth, and ultimately, all is prepared for the feast.

These words carry tremendous meanings, both on a simple level and on a mystical one, and require a great deal of contemplation. If we can summarize them in two lines: We should be exceedingly careful with our words and actions, strive to treat everyone with utmost care and respect, and remember that a time will come when we will have to account for—and pay for—all of our deeds. We should be grateful every single moment of every single day for what we have and who we are, and should remember always that God is good and just, and that all things happen for a reason.