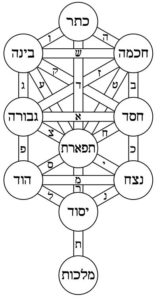

Purim is a deeply mystical holiday. In fact, Megillat Esther literally means “revealing the hidden”. While God is not explicitly mentioned anywhere in the Scroll, His fingerprints can be found all over it. In the same way, the Megillah is imbued with tremendous hidden wisdom. That it has a total of 10 chapters is the first clue, and if you read carefully, you will find that just about every Sefirah is mentioned!

The first Sefirah is Keter, the great “Crown” of God, and the first chapter of the Megillah is all about highlighting the greatness of Achashverosh’s crown and kingdom. Our Sages taught that Achashverosh wished to dress in the vestments of the kohen gadol, to “crown” himself as a king of the Jews (Megillah 12a). As is well-known, it was also taught that every time the Megillah refers to “the king” without a name, it is secretly referring to the King, to God. In Kabbalah, Keter always refers to Willpower (Ratzon), since the starting point of any endeavour is the will to do it. Everything begins with a will, and the universe began with God’s Will to create it, setting all of history in motion. Similarly, in the first chapter of the Megillah we find that Queen Vashti refuses to do the will of Achashverosh, thus setting the whole Purim story in motion.

The first Sefirah is Keter, the great “Crown” of God, and the first chapter of the Megillah is all about highlighting the greatness of Achashverosh’s crown and kingdom. Our Sages taught that Achashverosh wished to dress in the vestments of the kohen gadol, to “crown” himself as a king of the Jews (Megillah 12a). As is well-known, it was also taught that every time the Megillah refers to “the king” without a name, it is secretly referring to the King, to God. In Kabbalah, Keter always refers to Willpower (Ratzon), since the starting point of any endeavour is the will to do it. Everything begins with a will, and the universe began with God’s Will to create it, setting all of history in motion. Similarly, in the first chapter of the Megillah we find that Queen Vashti refuses to do the will of Achashverosh, thus setting the whole Purim story in motion.

The second Sefirah is Chokhmah, and the second chapter begins by introducing us to Mordechai, the paragon of a chakham, a Jewish sage. In Kabbalah, Chokhmah is also called Abba, the “father”, and we are told that Mordechai plays the role of an adopted father for the orphaned Esther. The third Sefirah is Binah, and the third chapter begins by introducing Haman, a master manipulator who knew how to twist people’s binah, “understanding”. Our Sages asked (Chullin 139b): where is Haman alluded to in the Torah? They answered that he is found in the words hamin ha’etz, “from the Tree”, referring to the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3:11) Our Sages associate Haman with the Tree of Knowledge, the consumption of which brought evil into the world. According to one Kabbalistic view, the Tree of Life is associated with Chokhmah, while the Tree of Knowledge is associated with Binah, hence the mystical connection to Haman. It goes deeper. Continue reading