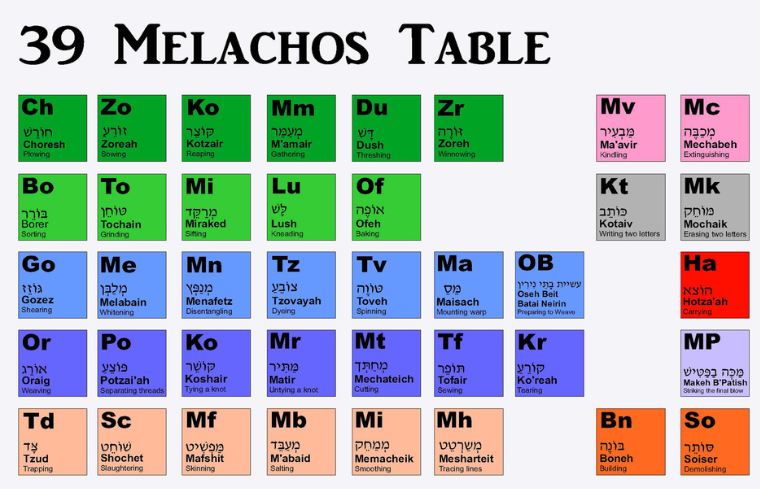

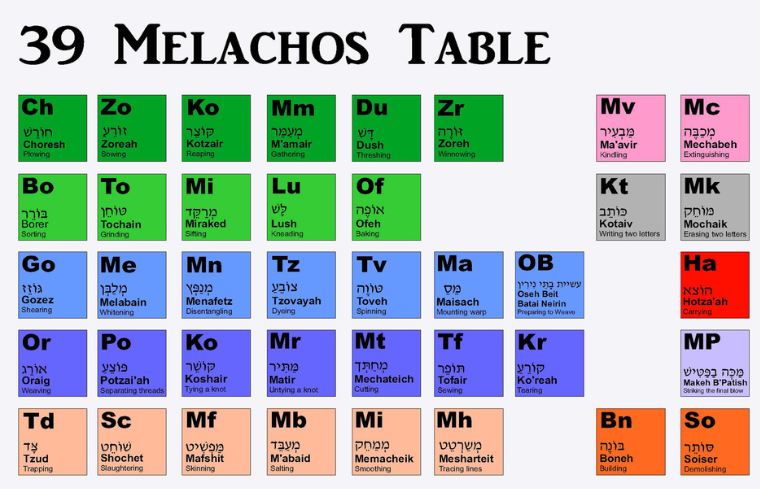

This week’s parasha, Vayak’hel, begins with the command to keep Shabbat, “six days shall you work, and on the seventh day will be for you a holy day of complete rest…” (Exodus 35:2) While Shabbat is mentioned numerous times in the Torah, it is this particular instance which served as the basis for our Sages to extrapolate the specific laws of Shabbat. Here, the Torah explicitly mentions only the prohibitions of working and lighting a fire. However, the Sages derived a list of 39 categories of prohibitions from the fact that God commanded the Sabbath, and right after juxtaposed it with the command to build the Mishkan. The Mishkan was not constructed on Shabbat, so all those actions that were required for the construction and operation of the Mishkan were forbidden on Shabbat.

There is a linguistic proof for this in the parasha because the type of work forbidden on Shabbat is specifically called melakhah, loosely translated as “creative labour”. The Sages note that this same term is used when speaking of the work required in building the Mishkan. In fact, they enumerate that this word is used 39 times in relation to the Mishkan (Shabbat 49b), hence 39 forms of labour. The Yerushalmi Talmud (Shabbat 44a) adds to this that the Shabbat mitzvah is introduced with the words eleh hadevarim, “these are the things”, implying there are multiple things that are forbidden on Shabbat. How many? The word eleh (אלה) has a numerical value of 36, while hadevarim (הדברים) implies three more things, since the plural devarim is a minimum of 2, and the definite hei at the start of the word suggests one more. Altogether, hadevarim is 3, and adding to eleh we get a total of 39 prohibitions! So, we rest on Shabbat from 39 major categories of activity.

A “Periodic Table” of the 39 Melakhot, by Anshie Kagan

Another big question that is often overlooked is this: why is Shabbat specifically the seventh day? Why did God create a week of 7 days to begin with? Why not 5 days, or 10 days? Why must we rest on the seventh day and not any other? What’s amazing is that there is no actual astronomical basis for keeping a week of 7 days. A year is a year because that’s how long it takes the Earth to orbit the sun, and a month is a month originally based on the amount of time it takes the moon to orbit the Earth. A week, however, is not related to any orbits or astronomical phenomena. This is why ancient cultures from around the world had weeks of varying lengths—and some had no concept of a “week” at all.

Ancient Rome once had an 8-day week, and ancient China followed a 10-day week. Today, the entire planet keeps a week of 7 days only because the Torah said so! Jews kept it first, of course, and then Christians and Muslims got the idea from the Torah, spreading it around the world. In fact, in their attempts to expunge religion for good, the Soviet Union introduced a 5-day week in 1929. Needless to say, it didn’t work. They probably got the idea from anti-religious French revolutionaries who introduced the “Republican calendar” in 1793 with a 10-day week. That one didn’t last long either.

The Meaning of 7

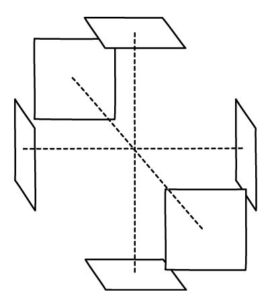

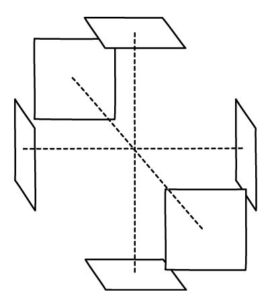

What is special about seven? We live in a universe that is 3 dimensional, resulting in six axes or directions (up, down, left, right, forward, backward), meaning that everything will inevitably have six outer faces. Six is therefore the number that represents the external and superficial. Seven is what is inside, representing the inner and the spiritual. In fact, the Hebrew word “seven”, sheva (שבע), is spelled the same way as sova or savea, to be “fulfilled”. All things spiritual or “internal” tend to be associated with the number seven. Light, when split to reveal its inner components, gives seven visible colours. Music is composed of a scale of seven distinct notes. The Heavens have seven levels (Chagigah 12b). The holiest month of the Hebrew calendar (and, somewhat paradoxically, the first of the new year) is the seventh month, Tishrei. For the same reasons, Shabbat is the seventh day of the week, being a day devoted to spirituality and holiness. The first six days of the week represent the physical realm, and we are required to work and be materially productive. Shabbat, the seventh day, is for the soul.

The three axes (x, y, z) of our three-dimensional reality, and the six faces (or six directions) that they produce.

Shabbat is the day when God’s Divine Presence, the Shekhinah, is most revealed and accessible. The Shekhinah itself is associated with the seventh of the lower Sefirot, called Malkhut. On that note, the seven days of the week actually correspond to the seven lower Sefirot (see Sha’ar HaMitzvot on Behar). Sunday is Chessed, Monday is Gevurah, Tuesday is Tiferet, and so on. These also correspond to the seven visible luminaries in the sky above us: sun and moon, and the five planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn (the other planets are not visible to the naked eye and were only discovered after the invention of the telescope). In his Discourse on Rosh HaShanah, the Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, 1194-1270) explains that pagans named their days of the week after these luminaries (and their corresponding deities). In English: Saturday after Saturn, Sunday after the sun, Monday after the moon, and Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday after the Norse gods Tiw, Odin, Thor, and Frigga. In French: Lundi for Luna (the moon), Mardi for Mars, Mercredi for Mercury, Jeudi for Jupiter, Vendredi for Venus. Contrary to them, the Ramban points out that Jews call the days of the week numerically in relation to the holy Shabbat: yom rishon, yom sheni, etc.

The Sages do admit that the luminaries have a spiritual influence on the events and people of this planet (Shabbat 156a). However, Israel is able to break free from this astrological influence and determine their own fate. (For more, see ‘Astrology and Astronomy in Judaism’.) The Ba’al HaTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, 1269-1343) interestingly notes how in olden days the Jewish court would convene on Thursdays because the Torah says b’tzedek tishpot (Leviticus 19:15), “you shall rule justly”, and tzedek also happens to be the Hebrew name of the planet Jupiter, which “rules” over Thursday! (The beit din would also convene on Mondays which, Kabbalistically, is the day of Gevurah and Din, “judgement”.) Saturn, with its beautiful rings and record-number of moons, is associated with Shabbat, and in fact it is called Shabbatai in Hebrew. Historically, the pagans always held Saturn as the greatest of their “gods”, while in Judaism it simply corresponds to the greatest day of the week.

Saturn

Finally, the Arizal notes (in Sha’ar Ruach HaKodesh) that on each day of the week a different one of the four mystical olamot, parallel “worlds” or “universes”, is revealed and made more accessible. We inhabit and see all around us the world of Asiyah, which has its greatest expression on Tuesday and Wednesday. Above that is the world of Yetzirah, more accessible and visible on Monday and Thursday (the days when the Torah is read publicly in the synagogue). Higher still is Beriah, revealed on Sunday and Friday, the days immediately before and after the Sabbath, into which some of the Shabbat holiness “spills” over. It is only on Shabbat that we can more easily access the highest of the worlds, Atzilut, and get a true sense of God’s infinite emanation.

In their rapid expansion, one of the new towns that the Khazars established was on the Dnieper River, and they called the town “Sambat”. Historians are uncertain what this word means or where it comes from. Considering the Jewish background of the Khazar kings, it is quite likely that the name comes from the legendary Jewish river, the Sambatyon. It was long believed that the Lost Tribes of Israel—exiled back in the middle of the first millennium BCE—had been resettled in distant lands past the mysterious Sambatyon River. The name “Sambatyon” itself comes from “Shabbat”, as it was said the Sambatyon River would only be calm on the Sabbath, when it could not be traversed. It is possible that the Khazars who founded this town were Jews who believed the Dnieper was the Sambatyon. Or it could be that they were Jewish settlers who stopped there one Shabbat to rest, and realized it was a good place to stay, hence the name. Whatever the case, by the 10th century, Sambat was better-known by another name: Kiev.

In their rapid expansion, one of the new towns that the Khazars established was on the Dnieper River, and they called the town “Sambat”. Historians are uncertain what this word means or where it comes from. Considering the Jewish background of the Khazar kings, it is quite likely that the name comes from the legendary Jewish river, the Sambatyon. It was long believed that the Lost Tribes of Israel—exiled back in the middle of the first millennium BCE—had been resettled in distant lands past the mysterious Sambatyon River. The name “Sambatyon” itself comes from “Shabbat”, as it was said the Sambatyon River would only be calm on the Sabbath, when it could not be traversed. It is possible that the Khazars who founded this town were Jews who believed the Dnieper was the Sambatyon. Or it could be that they were Jewish settlers who stopped there one Shabbat to rest, and realized it was a good place to stay, hence the name. Whatever the case, by the 10th century, Sambat was better-known by another name: Kiev.