This week’s double parasha, Behar-Bechukotai, begins: “And God spoke to Moses on Mt. Sinai: Speak to the Children of Israel and say to them: When you enter the land that I give you, the land shall observe a sabbath to God…” (Leviticus 25:1-2) As is well-known, the Holy Land must be worked for six years, and then left fallow in the seventh “Sabbatical” year, the Shemittah. After seven such cycles, the fiftieth year is the great Jubilee. After explaining the basic peshat meaning of these verses in his commentary, Rabbeinu Bechaye (Rabbi Bechaye ben Asher, 1255-1340) gives an explanation al derekh Kabbalah:

“the land shall observe a sabbath to God…” refers to the [seventh] millennium of “desolation”, which is entirely a sabbath of eternal rest. This is a reference to the World to Come, following the Resurrection… “You shall sanctify the fiftieth year and you shall proclaim freedom throughout the land for all its inhabitants. It shall be a Jubilee…” refers to each of the seven “days” of 7000 years, making a total of 49,000 years, after which the cosmos will return to a state of tohu v’vohu… (Rabbeinu Bechaye on Leviticus 25:2-10)

Rabbeinu Bechaye is speaking of the ancient mystical doctrine of the Cosmic Shemittot. Just as there is a 49-year cycle in the Holy Land, the entire cosmos goes through a 49,000-year cosmic cycle. Each of the 7000-year periods correspond to one “day” of Creation. Each period consists of 6000 years of civilization, followed by a resting seventh millennium which is Olam HaBa, the World to Come, corresponding to the delightful and spiritual Shabbat, before restarting a new era of civilization. After 49,000 years, there is a cosmic Jubilee, and the cycle restarts again.

Raphael Shuchat points out that the first mention of this notion goes all the way back to the Second Temple era, to the apocryphal Second Book of Enoch. Recall that Hanokh (“Enoch”) never died, and was transformed into an angel when God “took him” (Genesis 5:23-24). The Book of Enoch is attributed to him, but was not accepted into the official Tanakh canon by our Sages. Nonetheless, the Zohar quotes from the book dozens of times. It was most likely kept outside of the Tanakh, as one of the sifrei hitzonim, because it was too mystical and esoteric.

In the Book of Enoch, we read that God showed Hanokh the entire span of 7000 years, each day corresponding to a millennium. Then “the eighth day will be the first of a [newly] created week, and it thus revolves in a cycle of seven thousand…” (II Enoch 33) The Zohar similarly says there is a civilization span of 7000 years (III, 9b). The Talmud mentions this briefly in several places, too, including Rosh Hashanah 31a and Sanhedrin 97a. In both cases, there is another opinion presented that the Sabbatical millennium is not one thousand years, but two thousand years. This is probably referring to the final Sabbatical and the Jubilee together, since the 49th millennium is a Sabbatical, and then the 50th is the Jubilee, meaning there would be two thousand years of rest at the very end of the cycle. This seems to be the position of the Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, “Nahmanides”, 1194-1270) who described the cycle as being a total of 50,000 years, not 49,000 years. He explained (on Leviticus 25:2) that these 50,000 years are the secret of Nun Sha’arei Binah, the “Fifty Gates of Understanding”. And, when the Sages state that God revealed to Moses all Fifty Gates except the last (Rosh Hashanah 21b), it means God showed Moses nearly the entire span—some 49,000 years of hidden history—except for the final fiftieth Jubilee millennium!

This position is also held by the ancient Sefer haTemunah, one of the oldest Kabbalistic texts. The main focus of this book is to explain the mystery of the divine Hebrew alphabet, and the secrets of the shapes of the letters. It is an important work not only for Jewish mysticism, but even halakhah, since it is used as a source for proper Torah scribing. Sefer haTemunah speaks of the cosmic cycle, too, and connects it to the Fifty Gates. Intriguingly, it posits that we are currently in the second Shemittah, meaning there was already a previous era of civilization before ours.

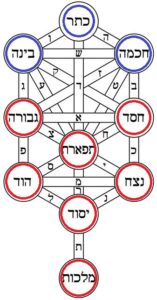

The Sefirot of Mochin above (in blue) and the Sefirot of the Middot below (in red) on the mystical “Tree of Life”.

Now, each of the seven cycles of seven thousand correspond to the seven lower Sefirot, the Middot or qualities. Thus, the first era of civilization was one of Chessed, “kindness” and positivity, while the second era, the one in which we are currently, is Gevurah, “severity” and judgement. This explains why the world we know is so difficult and full of evil and suffering. Similarly, the Kabbalists explain that the Torah manifests itself differently in each Shemittah. Since we are in the Shemittah of Gevurah and Din, the Torah in this iteration manifests itself as being full of laws, restrictions, punishments, and the like. In our reality, halakhah takes primacy. It seems that in the previous era, of Chessed, it was the aggadah that was primary, and not the halakhah, and the Torah was expressed in a much softer manner. According to some later sources, in each Shemittah it is the same Torah with the exact same set of letters, but they are rearranged!

A different opinion is that we are currently not in the second Shemittah, but in the fourth. This is discussed by Tiferet Yisrael (Rabbi Yisrael Lifschitz, 1782-1860) in his Derush Or HaChaim, at the end of his Mishnah commentary on Nezikin. He uses the doctrine of Cosmic Shemittot to explain why scientists find ancient fossils and archaeological remains, reasoning that these must be the remnants of past Shemittah civilizations! He interprets the earlier sources a little differently, and says this is the second Shemittah that has human life, but the fourth Shemittah altogether. He says that this is secretly encoded in the first letter of the Torah: the beit of Beresheet is written large to indicate that we are in the second Shemittah that has human life, and the beit is written with four tagin, “crowns”, to secretly encode that we are in the fourth Shemittah overall. Tiferet Yisrael adds that this is the secret of our Sages’ statement that there were 974 generations before Adam (Chagigah 13b-14a, Shabbat 88b). These are the generations of past Shemittot.

Rabbi Yisrael Lifschitz (1782-1860), “Tiferes Yisroel”

Yet another opinion is that we are already in the seventh Shemittah. This was the preferred choice of Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, who went into the subject in depth in Immortality, Resurrection, and the Age of the Universe. Rabbi Kaplan favoured this one because it allowed for a calculation that fit most closely with scientific estimates of the age of the universe. He cited sources that say there were already 42,000 years before Adam was created, putting us in the seventh era of Malkhut. This also makes sense because Malkhut is typically described as being “empty” and “lowly”, with no light of its own, which might reflect the reality in which we exist.

Whatever the case, we have an abundance of Torah evidence going all the way back to the Second Temple era that the notion of Cosmic Shemittot is not only legitimate, but accepted by major authorities. However, the Arizal (Rabbi Itzchak Luria, 1534-1572) seemed to be opposed to this notion, and held that the earlier generations simply misunderstood the spiritual dimensions. There are some today who still cite the Arizal in opposing the notion of Cosmic Shemittot. But, if we are going to be honest and rational, can we really say that all of the greats of the past were wrong? The Ibn Ezra, the Ramban, and Rabbeinu Bechaye could not understand spiritual realities? That Sefer Hanokh (cited countless times in the Zohar) and Sefer HaTemunah (which is also an halakhic text) were mistaken? That even the Sages of the Talmud, and the references in the Midrash (such as Kohelet Rabbah 3:11) and Zohar (including III, 61a-b which explicitly states that the souls of this world existed in previous worlds) can’t be taken at face value? In the big picture of Kabbalah, it’s the Arizal (and the Ramak) against everyone else, including major Rishonim and fundamental ancient texts. Rabbi Kaplan writes:

Since this is not a matter of law, there is no binding opinion. Although the Ari may have been the greatest of Kabbalists, his opinion on this matter is by no means absolutely binding. Since there were many important Kabbalists who upheld the concept of Sabbatical cycles, it is a valid, acceptable opinion. (pg. 6-7)

And the reality is, recent scientific and archaeological findings strongly support the notion of Cosmic Shemittot, too.

The Physical Evidence

Archaeologists have found many structures around the world that date far older than previously thought. The most famous example might be the Great Pyramids of Giza and the nearby Sphinx. Though typically dated to about 4000 years old, evidence suggests that they are much older. The Sphinx, in particular, has many layers of water erosion at its base, suggesting that it has lived through years of rainy weather. In recent millennia, Egypt does not have rain, of course. However, meteorological analysis and satellite scans suggest that Egypt was once part of a massive rainforest that spanned what is now the Sahara Desert. Based on new data, some have suggested the Sphinx is something like 12,000 years old, having been built at a time when Egypt’s weather was rainy and wet. Another well-known example is that of Göbekli Tepe, an ancient city unearthed in Turkey that has been dated back some 11,500 years, and sports the world’s oldest known temple. Similarly, the Tel es-Sultan site in Israel, near today’s Jericho, has been dated back to around the same time. And there are many others.

The Sphinx

Tel es-Sultan near Jericho, Israel

The town of Göbekli Tepe in modern-day Turkey dates back some 11,500 years.

Because of these reasons, some have proposed that we should change our year-counting system to start from the earliest signs of complex civilization, and instead of saying we are in 2023 CE, simply add ten thousand on top and say we are in 12023 HE (Human Era or Holocene Era). This happens to fit quite perfectly with Cosmic Shemittot. If we go with the earliest and most authoritative text—Sefer haTemunah—and say we are in the second Shemittah, then we need to add 7000 to our current Jewish year of 5783, making it the cosmic year 12,783 of the cycle! The archaeological evidence strongly supports Sefer haTemunah, as does the general idea that our civilization is full of war, misery, and suffering corresponding to the second middah of Gevurah, and the notion that the current Torah reality is one of strict halakhah and din.

All of this fits well with the increasingly popular “Younger Dryas” hypothesis positing that great civilizations first emerged at the end of the last ice age, about 12,000 years ago, when we suddenly see rising temperatures and rising sea levels all around the planet. There is even a far-out hypothesis arguing that the moon only entered Earth’s orbit about 12,000 years ago (!) and this may be what caused the drastic changes of the Younger Dryas in the first place.

Truly, there is no reason to stop at 12,000, since we can say that the current 50,000 year cycle is not the first, and there were previous Jubilees as well. (In fact, one might argue that we are in the second Shemittah of the second Jubilee, making our reality a Gevurah sh’b’Gevurah era.) This might explain even older pieces of archaeological and scientific evidence. It is worth mentioning that Earth’s rotation and tilt has its own cycle of about 41,000 years, with a wobble that makes the tilt shift between maximums of 22.1 and a 24.5-degree tilts, with massive repercussions for weather and climate. (Recall that it is Earth’s tilt that gives rise to the seasons.) According to scientists, the last maximum tilt position is estimated to have occurred about 10,700 years ago.

To conclude, the mystical notion of Cosmic Shemittot is not only valid and kosher, but attested to by a large number of ancient sources, including the Talmud and Zohar, and many great Kabbalists and Rishonim. It is absolutely fundamental for making sense of Creation and cosmogony, along with a plethora of scientific, archaeological, and historical findings. While it remains to be seen exactly which Shemittah we are currently in, much evidence supports the earliest position that we are in the second, though it may very well be that this is not the first cycle altogether. Either way, as we approach the end of our sixth millennium, we get closer and closer each day to the seventh Sabbatical millennium of universal rest, holiness, and elevation.