This week we commemorate Yom Ha’Atzmaut, the State of Israel’s Independence Day, marking seventy years since its founding. Although the State is certainly far from perfect, its establishment and continued existence is without a doubt one of the greatest developments in Jewish history. Many have seen it as the first steps towards the final redemption, and even among Haredi rabbis (which are generally opposed to the secular State) there were those who bravely admitted Israel’s significance and validity. Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach (1910-1995), for example, considered the State as Malkhut Israel, a valid Jewish “kingdom”—at least for halakhic purposes—while the recently deceased Rav Shteinman unceasingly supported the Nachal Haredi religious IDF unit despite the great deal of controversy it brought him. Rav Ovadia Yosef permitted saying Hallel without a blessing on Yom Ha’Atzmaut, and some have even composed an Al HaNissim text to be recited. While we have already written in the past about the significance of the State’s founding (along with one perspective to bridge together the secular and the religious on this issue), there is something particularly special about Israel’s 70th birthday.

This week we commemorate Yom Ha’Atzmaut, the State of Israel’s Independence Day, marking seventy years since its founding. Although the State is certainly far from perfect, its establishment and continued existence is without a doubt one of the greatest developments in Jewish history. Many have seen it as the first steps towards the final redemption, and even among Haredi rabbis (which are generally opposed to the secular State) there were those who bravely admitted Israel’s significance and validity. Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach (1910-1995), for example, considered the State as Malkhut Israel, a valid Jewish “kingdom”—at least for halakhic purposes—while the recently deceased Rav Shteinman unceasingly supported the Nachal Haredi religious IDF unit despite the great deal of controversy it brought him. Rav Ovadia Yosef permitted saying Hallel without a blessing on Yom Ha’Atzmaut, and some have even composed an Al HaNissim text to be recited. While we have already written in the past about the significance of the State’s founding (along with one perspective to bridge together the secular and the religious on this issue), there is something particularly special about Israel’s 70th birthday.

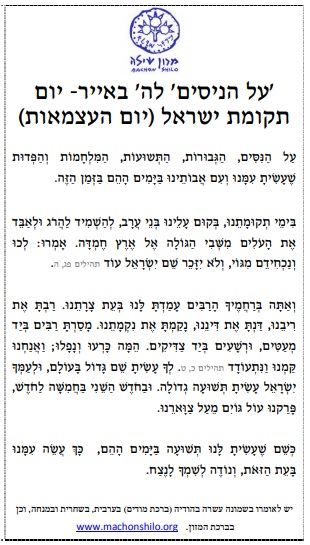

Al HaNissim for the Amidah and Birkat HaMazon provided by Rav David Bar-Hayim of Machon Shilo

The number 70 holds tremendous significance in Judaism. It is the number of root languages and root nations in the world (with Israel traditionally described as “a sheep among seventy wolves”). It is the number of Jacob’s family that descended to Egypt and from whom sprung up the entire nation. The number of elders that assisted Moses, and parallel to them the number of sages that sat on the Sanhedrin. Although Moses lived 120 years, he wrote in his psalm that 70 years is considered a complete lifespan (Psalms 90:10), and King David, who put the final edit on that psalm and incorporated it into his book, lived precisely 70 years. As is well-known, David was granted those 70 years by Adam, which is why the Torah says Adam lived 930 years instead of the expected 1000 years. (See here for how he may have been able to live so long.)

The Arizal taught that Adam (אדם) stands for Adam, David, and Mashiach, for the final redeemer is both a reflection of the first man, and the scion of David. More amazingly, as we wrote earlier this year it is said that David is literally the middle-point in history between Adam and Mashiach, and as such, if one counts the years elapsed between Adam and David then it is possible to find the start of the messianic era—which just happens to be our current year 5778. In this year, the State of Israel itself turns 70, and our Sages speak of “seventy cries of the soul during labour”, and parallel to these, “seventy cries of the birthpangs of Mashiach”. It is possible to interpret these seventy birthpangs preceding the arrival of the messiah as the seventy years leading up to the redemption. Thus, Israel’s seventy years potentially bear great significance.

Just as Psalms says that seventy years is one complete lifespan, for the State of Israel these past seventy years can be likened to the end of one “lifetime”, with Israel now standing at the cusp of a new era. Indeed, with all that has happened in the Middle East in recent years and months, Israel has undoubtedly emerged stronger and more secure than ever before. In this seventieth year, the world has begun to recognize Israel’s permanence, and affirm its unwavering right to Jerusalem the Eternal. We see more and more nations formally recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s rightful capital, and the United States plans to open its new Jerusalem embassy on May 14, which is Yom Ha’Atzmaut according to the secular calendar.

These seemingly disparate points—David’s seventy years, the completion of Israel’s first seventy year lifespan, and the recognition of Jerusalem—are actually intricately connected, for it was King David who established the first official, unified, Jewish state in the Holy Land, with Jerusalem as its capital. In fact, David’s kingdom was the only fully independent, unified Jewish state until the modern State of Israel! (Other Jewish entities, including the Maccabean and Herodian, were essentially always vassals to some greater power like Greece or Rome.) It is therefore quite fitting that the State of Israel has the Star of David on its flag, and it is this Davidic symbol that has become emblematic of not just Israel itself but all of modern Judaism.*

Living Prophecy

Perhaps the most famous seventy in Scripture is the seventy year period of exile in Babylon, between the First and Second Temples. It is said that God decreed a seventy year exile in particular because Israel failed to keep seventy Sabbatical and Jubilee years between the settling of Israel under Joshua and the destruction of the First Temple. While the Exile was certainly a “punishment”, we know that God never truly “punishes” Israel, and out of each devastation (which is nothing more than a just measure-for-measure retribution) emerges something greater.

As we’ve written before, it is in Babylon that the vibrant Judaism that we know was born. (See ‘The First Jewish Holiday’ in Garments of Light.) Unable to journey to the Temple, the Sages reworked each holiday to become more than a pilgrimage; unable to offer sacrifices, the Sages established prayers instead, “paying the cows with our lips” (Hosea 14:3); unable to fulfil the many agricultural laws, the Sages taught that learning the laws was as good as observing them. The Judaism of study, prayer, and mysticism was born out of the difficulty of the seventy-year Babylonian Exile. These past seventy years for Israel—also of great difficulty, and coming on the heels of another great devastation—was similarly one where Judaism has evolved considerably, and instead of dying out as some feared, has actually flourished.

Many have pointed out another modern “Babylonian Exile”, too. This is the communist regime of the Soviet Union, where millions of Jews were trapped for some seventy years. (The officially accepted start and end dates for the USSR are December 30, 1922 to December 26, 1991.) The histories of Russia and Israel are tightly bound, for many of Israel’s founders came directly from the Russian Empire, including Ze’ev Jabotinsky, Golda Meir, and the Netanyahus. Some even argue that the severe persecution by the Russians—unrivaled until the Nazis—is what gave the greatest motivation for the founding of Israel. The Kishinev Pogrom of 1903 was the final straw for the Zionists. The description of that pogrom by Bialik (another Russian Jew, and later Israel’s national poet) aroused the masses to take up the call and make aliyah, and convinced many more of the necessity of an independent Jewish state.

Russia’s involvement is all the more significant when we consider the possibility of Moscow as the prophesied “Third Rome”. As explored in the past, the “Red Army” headquartered in Moscow’s Red Square brings to mind the villainous Edom. Just as Rabbi Yose ben Kisma taught long ago in the Talmud (Sanhedrin 98a-b) that Mashiach will come when Rome/Edom falls for the third time, and there will not be a fourth, the Russian monk Filofey of Pskov (1465-1542) wrote of Moscow that “Two Romes have fallen, the third stands, and there will be no fourth.” This is all the more interesting in light of what we see in the news today about the growing conflict between the West and the Russia-Syria-Iran axis. It is important to keep in mind that Iran (Paras or Persia) is explicitly mentioned in Ezekiel’s prophecy of the great wars of the End of Days, the wars referred to as Gog u’Magog. The Midrash (Yalkut Shimoni on Isaiah 60, siman 499) comments on this that

In the year that Mashiach will be revealed, all the kings of the nations of the world will provoke each other. The king of Persia will threaten the king of Arabia, and the king of Arabia will go to Aram for advice. The king of Persia will then destroy the world, and all the nations will tremble and fall upon their faces, and they will be grasped by birthpangs like the birthpangs of labour, and Israel, too, will tremble and falter, and they will ask: “Where will we go?” And [God] will answer: “My children, do not fear, for all that I have done, I have done for you… the time of your salvation has come.”

Those who follow geopolitics will immediately identify this midrashic passage with current events. The war in Syria is very much a proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran, just as is the war currently raging in Yemen. Saudi Arabia has joined the Western (Aram?) camp, and has even begun to speak positively of Israel in public. The prophet Jeremiah (49:27) further details that Syria will be the epicenter of the war, and the “end” will come when Damascus has fallen. Amazingly, Jeremiah calls the king of Damascus Ben Hadad (בן הדד), the gematria of which happens to equal Assad (אסד). And it also happens that the value of Gog u’Magog (גוג ומגוג) is 70.

Top right: Arab Coalition forces led by Saudi Arabia (and backed by the US, UK, and France) fighting in Yemen to defeat Iran-backed Houthi rebels. Bottom right: Today in the news we read about Saudi Arabia considering sending ground forces into Syria, where Iranian Revolutionary Guards are deeply entrenched. Some say Saudi Arabia secretly has forces in Syria already. It is highly likely that there are Russian and American paramilitary groups in Syria as well. Turkish and Israeli forces are heavily involved, too, and the US, UK, and France recently launched a missile strike on Syrian facilities.

Thus, Israel turning 70 carries remarkable symbolic meaning. The Midrash states that Israel has 70 names, and these correspond to the 70 names of the Torah (and the Torah’s 70 layers of meaning, to be revealed in full with Mashiach’s coming), as well as the 70 Names of God, and the 70 names for the holy city of Jerusalem. The last of these names, the Midrash says (based on Isaiah 62:2), is “a new name that God will reveal in the End of Days.” The struggle over Jerusalem and the Holy Land will soon end, with a new city and a new name to be reborn in its place.

May we merit to see it soon.

Courtesy: Temple Institute

*Judaism began with Abraham. In an amazing “coincidence” of numbers, Jewish tradition holds that Abraham was born in the Hebrew year 1948. The State of Israel was, of course, born in the secular year 1948. Jewish tradition also holds that Abraham was 70 years old at the “Covenant Between the Parts”, when God officially appointed Abraham as His chosen one. This means the Covenant took place in the Jewish year 2018, paralleling Israel’s 70th birthday in this secular year of 2018.