This week’s parasha, Lech Lecha, begins in the year 2023—of the Hebrew calendar, that is. In traditional Jewish chronology, Abraham was born in the year 1948 AM (Anno Mundi, or “world year”). At the start of the parasha, we are told that Abraham was 75 years old when he settled in the Holy Land, meaning it was 2023 AM. Many have pointed out the intriguing “coincidence” that the forefather of the Jewish people and the first to settle in Israel was born in the same numerical year as was born the State of Israel and the Jewish people’s return to independence in the Holy Land in 1948 CE. More amazingly, we find that key dates in the life of Abraham align with key dates for the State of Israel, all the way up to the present situation that we find ourselves in today.

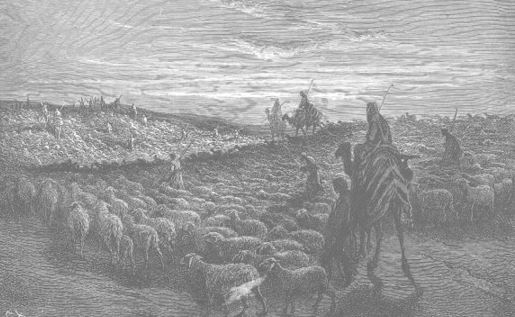

‘Abraham Journeying to the Land of Canaan’, by Gustav Doré

The Torah has very little to say about Abraham’s early life. In fact, all it tells us is that he was born, got married, and left Ur-Kasdim. The Torah then jumps ahead to his 75th birthday. What happened in the first half of Abraham’s life? Rabbinic tradition fills in a lot of the details, including that he was imprisoned for ten years! (Bava Batra 91a) At the end of that decade came the most notable event of Abraham’s early life: He was brought before the king and commanded to abandon monotheism and worship idols. Abraham refused, and was thrown into a fiery furnace. God miraculously saved him—marking the first time God openly revealed Himself to Abraham. Immediately after this, Abraham left Ur to settle in Haran. This event happened when Abraham was 52 years old, in the year 2000 AM. It launched what the Talmud calls “the Era of Torah”, lasting 2000 years until 4000 AM. (The first 2000 years of history, starting from Adam, were called “the Era of Chaos”.)

We find a similar monumental shift for the State of Israel in the year 2000 CE. A few key things happened then. In May of 2000, the IDF withdrew from southern Lebanon, where they had been stationed since 1982. This allowed for Hezbollah’s subsequent takeover of the region. (Just a few months later, Hezbollah terrorists launched a cross-border raid and abducted three Israeli soldiers.) In July of 2000, Prime Minister Ehud Barak headed to Washington for the Camp David Summit with Bill Clinton and Yasser Arafat. Barak offered Arafat just about everything he wanted, including all of Gaza and over 95% of the West Bank, with land transfers to make up for the other parts. Arafat notoriously walked away from the table without offering any explanation why, then launched the Second Intifada. A peaceful resolution to the conflict was not in the interest of the corrupt Palestinian leadership.

These events were the nail in the coffin for the Oslo Accords, and proved that the Palestinian leadership didn’t care for any two-state solution. Their goals were obvious: the destruction of the State of Israel and the takeover of the entire region “from the River to the Sea”. The peace process had always been a ruse. That year, 2000, officially marked the death of the peace process, and wiped away the possibility for a two-state solution. The majority of the Israeli population woke up to realize that peace had only been a dream. Since then, Israeli society has noticeably and understandably shifted right-ward. More broadly, the years that followed saw a religious revival in Israel and in Jewish communities around the world, with a large and global baal teshuva movement reminiscent of Abraham’s “Era of Torah”. Thus, just as the year 2000 AM marked a great shift in the life of Abraham, the year 2000 CE marked a great shift in the life of the State of Israel and Jews worldwide. The parallels don’t end there.

After 23 years living in Haran, God commanded Abraham to finally settle in the Promised Land. However, Abraham was confronted with a difficult reality upon arrival. There were hostile Canaanites in the land (Genesis 12:6), as well as rampant famine (12:10), forcing Abraham to head south to Egypt. There, his wife Sarah was abducted. After returning to the Holy Land, Abraham settled between Beit El and Ai. He finally found prosperity, but this led to quarrels within the family, particularly with his nephew Lot. And so, we find that in 2023 AM, Abraham experienced economic difficulties, hostile neighbours, abductions of family members, and internecine brotherly conflict, much like the people of Israel have experienced in 2023 CE.

Some years later, a war came to the Holy Land, with the Sodomite confederation of five cities falling to an alliance of four Mesopotamian kings. Many of the Sodomites were taken captive, including Lot. Abraham went to war and rescued them. When the Sodomite king offered Abraham riches as a reward, Abraham refused and said he wouldn’t take even a “thread or shoe strap”. The Talmud (Sotah 17a) states that in the merit of this, Abraham’s descendants were gifted the mitzvot of tzitzit (the threads) and tefillin (the leather straps). Both contain immense spiritual power, and are said to confer protection to Jewish warriors. It is therefore fitting that there has been an immense desire for IDF soldiers to get tzitzit, and volunteers have tied over 60,000 shirts so far. Meanwhile, Jews around the world are newly inspired to lay tefillin, and over 2300 have already signed up to receive a free pair.

Right after the War of the Kings, God appeared to Abraham and Abraham complained that he was still without a child (Genesis 14). God allayed his concerns and told him he will indeed have much progeny. Right after this comes the account of the birth of Ishmael, forefather of all Arabs and, by extension, all Muslims. Ishmael was born when Abraham was 86 years old, in the year 2034 AM. Ishmael would go on to cause a lot of trouble, but our Sages say that he did ultimately repent and died a righteous man (see Rashi on Genesis 25:17).

What does all of this mean for us, as we look ahead to the next decade? Will things get worse before they get better? Will there be a larger, long-lasting regional war as in the days of Abraham? And will, at the end of it, the House of Ishmael experience a “rebirth” and find righteousness like their ancestor? Perhaps then we can finally have peace.

In the Torah’s chronology, the long-awaited Isaac would be born when Abraham was 100, in the year 2048 AM. And our Sages teach that Itzchak (יצחק) is ketz chai (קץ חי), symbolic of life at the End of Days. Isaac is the only forefather who dwelled securely in the Holy Land and never had to leave. He enjoyed me’ah she’arim, hundred-fold prosperity. The Zohar (I, 137a, Midrash haNe’elam) compares his “return” following the Akedah at age 40 to a “resurrection” of sorts, and sees this as a sign of the final Resurrection of the Dead, to come forty years into the Messianic Age. Based on the Abraham-Israel connection and the pattern outlined above, the Torah years of 2034 AM, 2048 AM, and 2088 AM might offer us hope to expect events of great significance to come in 2034 CE, 2048 CE, and 2088 CE.

As for the present, the Zohar (I, 83b) says that when Abraham entered the Holy Land at age 75, in the year 2023 AM, he received a brand new nefesh. It was like he became a totally new person. Then, when he went south (before going to Egypt) he received a new ruach, the second and higher soul. It was only years later, after returning from Egypt, parting from Lot, and becoming even more prominent—right before the onset of the War of the Kings—that Abraham received the lofty neshamah, at the moment when “he built an altar to God” (Genesis 13:18). For the State of Israel, too, 2023 CE will undoubtedly be the year that it received a brand new nefesh. In light of what has happened in recent weeks, the country will never be the same again, nor will its people. And following the model set by Abraham, the next decade will surely transform the country as it receives a new ruach, too, and eventually its true divine neshamah. We hope it will then become the proper holy kingdom of God that the State of Israel was always meant to be.