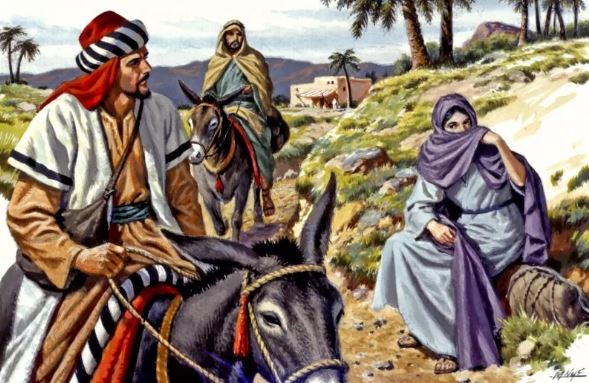

This week’s parasha, Vayetze, begins with Jacob setting forth towards his mother’s hometown in Haran. We read that on his way he suddenly “bumped into” a special place (Genesis 28:11) that turned out to be Beit El, the “House of God”. Jacob was surprised to find himself there (28:16), presumably the site of the future House of God, the Temple in Jerusalem. The Sages (Sanhedrin 95b) explain what happened:

“And Jacob went out from Be’er Sheva, and went to Haran…” is followed by “and he happened upon the place, and tarried there all night, because the sun was set.” For when he reached Haran, he said: “Shall I have passed through the place in which my fathers prayed, without doing so likewise?!” He wished therefore to return, but no sooner had he thought of this than the earth instantly contracted and he “happened upon” that place.

Our Sages state that a miracle occurred after Jacob had reached Haran. He regretted not stopping by at the site of the future Temple Mount, where Abraham and Isaac had prayed, so the earth beneath his feet seemingly “contracted” and he was suddenly teleported to Jerusalem. In fact, the Sages state that such a miracle occurred for three people in the Tanakh: first was Eliezer, Abraham’s servant, then Jacob in this week’s parasha, and finally King David’s general Avishai. There is Scriptural proof for each one. For instance, when Eliezer had arrived in Haran he declared “I came today to the well” (Genesis 24:42), implying he had set out on his journey that same day. Eliezer was miraculously able to go from Be’er Sheva to Haran, a significantly long journey, in under a day.

This phenomenon would later become known as kefitzat haderekh, “jumping the path”, and would appear in Rabbinic narratives as well. Angels have a similar ability to seemingly teleport across vast distances. In one story, Rav Kahana was once selling some wares and a female customer tried to seduce him (Kiddushin 40a). He quickly fled in distress and ran to the nearest window and jumped! The angel-prophet Eliyahu appeared and caught him, complaining that he had to instantly travel a distance of “four hundred parasangs” to save him. A parasang, or parsa, is the average distance a person walks in 72 minutes—generally thought to be about 5 kilometres. So, Eliyahu flew some 2000 kilometres in a flash to catch the rabbi. Rav Kahana apologized and lamented that due to his poverty he had to resort to being a salesman. Eliyahu gave him a vessel full of money to free him from his job.

Meanwhile, the Zohar (I, 4b-5a) states that the malevolent angel Samael can traverse as much as 6000 parsas in a single moment. This number is not arbitrary, for the Talmud calculates that the Earth’s circumference is 6000 parsas (Pesachim 94a). This is an incredible piece of Talmudic science, considering how little of the globe was known then. Today, we know that Earth’s exact circumference is 40,075 km at the equator, a value close to that of our Sages. In fact, if making the correct assumption that the Sages must have been exact in their knowledge, we might be able to properly identify the length of a Talmudic parsa.

Although it is generally calculated in halakhah that a parsa is between 4 and 5 kilometres, by dividing 40,075 km by 6000 we can conclude that a parsa must be closer to 6.68 kilometres. This is also more in line with the notion that a parsa is a distance of 72 minutes: The average walking speed of humans is 5 km per hour (1.42 metres per second, according to the most precise measurements), so defining a parsa as 6.68 km is much closer to the scientific reality.

Jacob’s Ladder through Spacetime

The Talmud (Chullin 91b) calculates that the distance of the Heavenly Ladder that Jacob saw in his vision was a whopping 8000 parsas, which would be over 50,000 km. The word used by our Sages is rochav, meaning “width”. A superficial reading of the Talmud suggests that each angel is 2000 parsas wide (based on Daniel 10:6), and since Jacob saw four angels, the width of the Ladder must have been 8000 parsas. However, this does not make sense if taken literally, for why would an angel’s form be 2000 parsas wide? And if it was, how could Jacob even capture the sight of an angel in his limited field of view? The Talmud must be teaching something else. The big question here is why use the language of width as opposed to length or height, as might be expected?

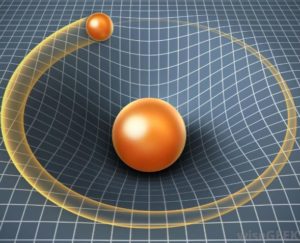

When it comes to understanding the cosmos, we always speak of a “fabric of spacetime”. Perhaps the greatest achievement of Albert Einstein is pioneering the science behind it, proving that the three dimensions of space and the dimension of time are not separate, but interwoven together. With this, he was able to explain gravity a lot more accurately, demonstrating that larger bodies make a bigger “dip” in the fabric, pulling objects towards them kind of like a penny rolling around a funnel. And because they are integrated, strong gravitational effects can warp both space and time. We typically visualize spacetime as a flat “fabric”, with celestial objects scattered all over it. In fact, today we know that the universe does indeed appear to be flat (with a margin of error of about 0.4%). This is of tremendous significance.

When it comes to understanding the cosmos, we always speak of a “fabric of spacetime”. Perhaps the greatest achievement of Albert Einstein is pioneering the science behind it, proving that the three dimensions of space and the dimension of time are not separate, but interwoven together. With this, he was able to explain gravity a lot more accurately, demonstrating that larger bodies make a bigger “dip” in the fabric, pulling objects towards them kind of like a penny rolling around a funnel. And because they are integrated, strong gravitational effects can warp both space and time. We typically visualize spacetime as a flat “fabric”, with celestial objects scattered all over it. In fact, today we know that the universe does indeed appear to be flat (with a margin of error of about 0.4%). This is of tremendous significance.

In the Torah, the term aretz can refer to both Earth proper, and the wider physical universe at large. When we read that in the beginning God created et shamayim v’et ha’aretz, we do not define it simply as the “sky” and the “earth”, for those were not created until Days Two and Three. Rather, God created the entire spiritual realm (shamayim) and the entire physical universe (aretz). Our Sages noted long ago that the root of aretz (ארץ) is the same as ratz (רץ), “running”, since everything in this universe is in perpetual motion. More incredibly, today we know that the universe is constantly expanding, and we see distant stars “running away” from us. As such, when the Tanakh uses an idiom like kanfot ha’aretz, the “corners” or “edges” of the universe, it may be read quite literally. For a long time, there were people who understood these Torah statements as implying a flat Earth, when in reality they could have been alluding to a deeper scientific understanding regarding the “flatness” of the entire universe.

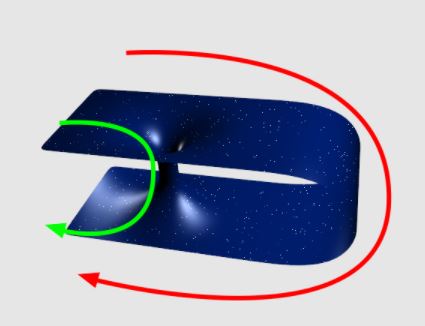

And that brings us back to the precise Talmudic language of rochav, “width”, in a place where we might have expected height. Of course, we do have a dimension of height. However, when zooming out to a “flat” universe, we really only visualize it in terms of width, as if on a two-dimensional plane. Going further, Einstein later showed, together with another Jewish scientist named Nathan Rosen, that it would be theoretically possible to “bend” spacetime and connect two points that are vastly far apart. It would be like folding over the fabric and then poking a hole through both layers. Such an “Einstein-Rosen bridge”, better known as a wormhole, would allow travel across extremely vast distances in a very short period of time. In other words, it would be very much like kefitzat haderekh!

So, what our Sages may have been secretly implying in describing the width of Jacob’s Ladder is that this wormhole (of sorts) spanned 8000 parsas, or over 50,000 km. This is a distance even wider than the Earth and, scientifically, we would expect wormholes to be very large like this. Such a wormhole was accurately depicted in the film Interstellar, allowing the protagonists to instantly travel to a distant solar system to find a new home for mankind:

It is worth noting that when our Sages described the teleportation of Jacob, they said that kaftzah ha’aretz, again using that term aretz, and implying that it “jumped” or “contracted” for him. So, another term for this phenomenon, truer to the language of the Talmud, would be kefitzat ha’aretz, the warping of the spacetime fabric of this universe. Kefitzat haderekh is accurate, too, implying that one “jumped the path”, finding an alternate shortcut from one point in the universe to another. This appears to have happened at Sinai, as well. Our Sages likened Jacob’s Ladder to the Sinai Revelation, and the Zohar (I, 149a, Sitrei Torah) even notes that the numerical value of “ladder” (סלם) and “Sinai” (סיני) is the same—130. At Sinai, too, a “wormhole” opened up allowing 22,000 angelic “chariots” to descend upon the mountain (Bamidbar Rabbah 2:3).

Theoretical physics aside, can we actually create such wormholes? In 2017, scientists succeeded in producing tiny, microscopic wormholes for the first time. It is certainly possible that in the near future we will have the technology to open up larger wormholes, making rapid travel across God’s vast universe feasible. It appears that God’s angels already employ such a wormhole-style system of travel, traversing thousands of parsas instantaneously. It might help explain the Tower of Babel episode which, as we’ve mentioned in the past, was not simply a tower but meant to “lift off” and “conquer” the Heavens.

Our Sages long ago taught that the people who built the Tower knew the wisdom of the angels and were using angelic powers to accomplish their plans (see, for instance, Zohar I, 76a). God “came down” to confound them. He wiped their memories and jumbled their languages so that they wouldn’t be able to collaborate in such a megalomaniacal way. Today, we live in a world that is once more getting real close to being “of singular language and singular words” (Genesis 11:1), and once again we see science stepping into the dangerous territory of “playing God”. Hopefully this time humanity will get it right and use the astounding abilities that God made possible in His universe only for the good.