In this week’s parasha, Matot-Massei, we read how the Israelites were supposed to divide up the Holy Land between the Twelve Tribes:

And you shall inherit the land by lot according to your families; to the more [numerous] you shall give the more inheritance, and to the fewer you shall give the lesser inheritance; wherever the lot falls to any man, that shall be his…

We learn that the land of Israel was apportioned based on family size, with larger families logically receiving a larger share. Now, to determine which chunk of land a family would receive, the Israelites cast lots. The Talmud (Bava Batra 122a) describes how this was done: two urns were prepared, one containing the names of the Twelve Tribes, and the other containing the names of the various allotments of land. Elazar the High Priest would pick one name from each urn, thus designating a piece of land for a particular tribe.

Casting lots was very common in Biblical times, and is mentioned frequently in the Tanakh. For example, the Torah commands casting lots to determine which goat is sent to Azazel on Yom Kippur (Leviticus 16:8). In the Book of Jonah (1:7), the sailors on Jonah’s ship cast lots to determine who was guilty of causing the storm. In the time of King David, the kohanim were thus divided into 24 groups (I Chronicles 24). Haman cast lots to determine the best day to attack the Jews, and this is why the holiday is called “Purim”, since purim was the Persian word for “lots” (Esther 3:7).

Casting lots suggests a large degree of chance or randomness in the process. Yet, people of faith are naturally quite averse to the concept of random chance, for isn’t everything determined by God? Not surprisingly, the word “lot” (goral) also takes on the meaning of “fate” in the Tanakh. For instance, Isaiah (17:14) prophesies: “At evening there will be terror, and before morning they are not. This is the portion of them that spoil us, and the goral of them that rob us.” The ultimate fate of those that harm the Jewish people will be utter destruction. The Sages, too, were uncomfortable with the idea of dividing the Holy Land by seemingly random lots. They therefore stated (ibid.) that the lots were really just a show for the people to see what God intended. In reality:

Elazar was wearing the Urim and Tumim, while Joshua and all Israel stood before him… Animated by the Holy Spirit, he gave directions, exclaiming: “Zevulun” is coming up and the boundary lines of Acco are coming up with it. [Thereupon], he shook well the urn of the tribes and Zevulun came up in his hand. [Likewise] he shook well the urn of the boundaries and the boundary lines of Acco came up in his hand…

Elazar would prophetically see which tribe needed which land, and when he then shook the urns those exact pairs that he foresaw would emerge! So, the process was not random at all, but simply a materialization of the Divine Will. Still, the Sages insist that in the messianic era the Holy Land will not be apportioned through this method of casting lots, but rather “The Holy One, blessed be He, Himself, will divide it among them; for it is said [Ezekiel 48:29], ‘And these are their portions, says the Lord God.’”

If the Sages were not fond of casting random lots by chance, how would they feel about playing games of chance and gambling?

Gambling in the Talmud

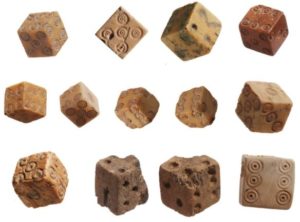

In 1999 and 2000, the Muslim Waqf (Temple Mount authority) dug up 9000 tons of Temple Mount soil and unceremoniously dumped it in the Kidron Valley, creating one of the largest archaeological catastrophes in history. Thankfully, archaeologists did not give up on this precious soil, and began the “Temple Mount Sifting Project”. Among the many incredible finds are these Second Temple-era playing dice.

In a list of people that are ineligible to serve as witnesses or as judges, the Mishnah includes a mesachek b’kubia, a person who plays with dice, and mafrichei yonim, “pigeon flyers”. According to the Talmud, the latter most likely refers to people who bet on pigeon races, which were apparently common in those days. We know from historical sources that gambling with various dice games was very popular in Greek and Roman times. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 24b) goes on to discuss what the problem with such people is.

Rami bar Hama teaches that the issue with gambling is that it is essentially built on a lie: each player agrees to pay a certain sum of money if they lose, yet they hope (and fully intend) not to lose at all! That means the initial agreement made by the players is not even valid. The losing gambler is entirely dejected, and gives up their money reluctantly, often with a nagging feeling of being robbed or cheated out of their money.

Rav Sheshet disagrees. After all, there may be some people who are not so sad to part with their money, or are simply addicted to the game itself. Whatever the case, Rav Sheshet holds that gambling is inappropriate because it is a terribly unproductive waste of time, and the gambler contributes nothing to “the welfare of the world”. This is why, Rav Sheshet says, the Mishnah above concludes by saying that only a full-time gambler is prohibited, but one who has an actual job and just plays for fun on the side is permitted.

Nonetheless, Rav Yehudah holds that regardless of whether the gambler has an occupation or not, or whether he is a full-time player or not, a gambler is disqualified from being a kosher witness or judge. Rav Yehudah bases his statement on a related teaching of Rabbi Tarfon, and on this Rashi comments that a gambler is likened to a thief. The Midrash is even more vocal, saying that gamblers “calculate with their left hand, and press with their right, and rob and wrong one another” (Midrash Tehillim on Psalm 26:10).

The Talmud (Sanhedrin 25b) goes on to state that the prohibitions above don’t only refer to a literal dice-player, but any kind of gambler, including one who plays with pebbles (or checkers), and even with nuts. The Sages state that such a person is only readmitted when they do a complete repentance, and refuse to play the game even just for fun without any money!

Halachically-speaking, the Shulchan Arukh (Choshen Mishpat 370:2-3) first states that any kind of gambling is like theft and is forbidden, but then suggests that while it may not exactly be theft it is certainly a waste of time and not something anyone should engage in.

A Ban on Gambling

While the Talmud does not explicitly forbid gambling, later rabbis recognized its addictive nature and sought to ban the practice entirely. In 1628, for example, the rabbis of Venice issued a decree (to last six years) excommunicating any Jew who gambled. Part of the motivation for this decree was the case of Leon da Modena (Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh of Modena, 1571-1648).

Rabbi Leon Yehudah Aryeh da Modena

Born in Venice to a family of Sephardic exiles, da Modena went on to become a respected rabbi and the hazzan of Venice’s main synagogue for forty years. A noted scholar, he wrote about a dozen important treatises. In Magen v’Herev, he systematically tore down the major tenets of Christianity, while in Ari Nohem he sought to discredit Kabbalah and prove that the Zohar has no ancient or divine origin. (The latter is probably why he isn’t as well-known in Jewish circles today as he should be.)

In 1637, he published Historia de’riti hebraici, an overview of Judaism for the European world, meant to dispel myths about Judaism and quell anti-Semitism. Historians credit this with being the first Jewish text written for the non-Jewish world in over a millennium, since the time of Josephus. The book was incredibly popular, and played a key role in England’s readmitting Jews to the country in the 1650s (after having being expelled in 1290).

More pertinent to the present discussion, Rabbi da Modena wrote Sur miRa (“Desist from Evil”), outlining the problems with gambling. He would know, since he was horribly addicted to gambling himself. He wrote of this problem in his own autobiography, Chayei Yehudah. And because such a high-profile sage was a gambler, his rabbinic colleagues in Venice issued that decree to ban any form of gambling.

Rabbi da Modena’s game of choice was cards. At that point in time, playing cards had become wildly popular in Europe. First invented in China in the 9th century, playing cards slowly made their way across Asia, and reached Europe around 1365. They have remained popular ever since, both for gambling and non-gambling games. While it is clear from an halachic standpoint that card games involving money (like Poker or Blackjack) should not be played, is it permissible to play non-gambling card games (like Crazy Eights or Go Fish)?

At first glance, it may not seem like there should be a problem with this. Yet, some rabbis have recently spoken out against all playing cards. Usually, this prohibition is connected not to gambling or wasting time, but rather to cards’ apparent origins in idolatry or the dark arts. Although it is true that some types of cards are used in divination and fortune-telling, it is important to examine the matter in depth and determine whether cards really are associated with forbidden practices.

The History of Playing Cards

Mamluk Cards

The exact origins of cards are unclear. We do know that they come from China, where paper and printing were invented. Card games are attested to in Chinese texts as early as 868 CE. In the 12th and 13th centuries, the Muslims brought cards across Asia. They were particularly popular in Egypt during the Mamluk Sultanate (1250-1517). The Mamluks created the first modern-style deck of 52 cards with 4 suits. The suits were sticks, coins, swords, and cups. In the 15th century, Italians started to make cards of their own, with the suits being leaves, hearts, bells, and acorns. The French had three-leaf clovers for leaves, square tiles (or diamonds) for bells, and pikes for acorns. Although these suit symbols remained, the English names reflect the earlier suits of sticks (“clubs”) and swords (“spades”).

The Muslim Mamluks did not draw any faces on their court cards (since depicting faces in art is forbidden in Islam). The Europeans did not have this issue, and adapted the Muslim court cards of malik (king), malik na’ib (deputy king), and thani na’ib (second deputy) to king, queen, and prince or knight (“jack”). In 16th century France, the four kings were depicted as particular historical figures: the King of Spades was King David, the King of Clubs was Alexander the Great, the King of Hearts was Charlemagne, and the King of Diamonds was Julius (or Augustus) Caesar.

The Muslim Mamluks did not draw any faces on their court cards (since depicting faces in art is forbidden in Islam). The Europeans did not have this issue, and adapted the Muslim court cards of malik (king), malik na’ib (deputy king), and thani na’ib (second deputy) to king, queen, and prince or knight (“jack”). In 16th century France, the four kings were depicted as particular historical figures: the King of Spades was King David, the King of Clubs was Alexander the Great, the King of Hearts was Charlemagne, and the King of Diamonds was Julius (or Augustus) Caesar.

We see that playing cards have no origins in idolatry. The style of cards we know today were developed by staunchly monotheistic Muslims. They were further developed by mostly non-religious European renaissance printers, against the wishes of the Church which sought to ban cards on a number of occasions. Neither are playing cards known for being used in fortune-telling. However, a related type of card is used in divination today.

Tarot Cards and Kabbalah

In 15th century Italy, a different type of playing card developed. These were called trionfi, later tarocchi, and finally “tarot cards”. They, too, have four suits, but with 56 cards. These were, and still are, used for a number of different games, just like regular playing cards are. Outside of Europe, tarot cards are not well-known, and are generally associated with fortune-tellers.

In reality, the earliest mention of tarot cards being used in divination is only from 1750, and it was essentially unheard of until the late 19th century. Besides, most diviners actually use a different deck of 78 cards. Of course, such divination is entirely forbidden according to the Torah. So, it seems like some well-meaning rabbis have confused these tarot cards with regular playing cards. Ironically, many occultists actually claim that tarot cards come from Kabbalah!

The Tarot “Tree of Life” (Credit: Byzant.com)

These occultists tie the 22 additional divination cards to the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet and the 22 paths on the mystical “Tree of Life”. The ten numeral cards (naturally) correspond to the Ten Sefirot, while the four suits correspond to the four olamot, or universes. Finally, the four court cards and the ace represent the five partzufim (with the king and queen appropriately being Aba and Ima). While these parallels are neat, there is absolutely no known historical or textual basis to support these claims. Tarot cards have nothing to do with traditional Kabbalah or Jewish mysticism. (There is a concept in Kabbalah of a negative set of Ten Sefirot belonging to the Sitra Achra, so perhaps there is some connection between these tarot cards and certain evil spiritual forces.)

Having said all that, to forbid playing with cards (or even standard tarot cards) just because some people recently started using them in divination is like forbidding drinking coffee because some people recently started divining with coffee (a practice called “tassology” or “tasseography”). While playing cards copiously is certainly a waste of time, there is nothing wrong with the occasional—no gambling—game.

Ba’al HaTurim

It is fitting to end with the words of the Ba’al HaTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, c. 1269-1343) who writes in his commentary on the Torah (Tur HaAroch on Deuteronomy 1:1) that Moses himself cautioned Israel about gambling in his final speech before passing away:

Before Moses got ready to relate all these various commandments, he used the present opportunity, a few weeks before his death, to admonish the people, and to remind them of past sins, and how they had caused Hashem a lot of grief during these years. He reminded them how God had treated them by invoking His attribute of mercy and loving kindness time and again. He warned them not to become corrupt again by gambling… They should not rely on the fact that because they were human they were bound to err and sin from time to time and that God, knowing this, would overlook their trespasses.

The above is adapted from Garments of Light, Volume Two. Get the book here!

The Muslim Mamluks did not draw any faces on their court cards (since depicting faces in art is forbidden in Islam). The Europeans did not have this issue, and adapted the Muslim court cards of malik (king), malik na’ib (deputy king), and thani na’ib (second deputy) to king, queen, and prince or knight (“jack”). In 16th century France, the four kings were depicted as particular historical figures: the King of Spades was King David, the King of Clubs was Alexander the Great, the King of Hearts was Charlemagne, and the King of Diamonds was Julius (or Augustus) Caesar.

The Muslim Mamluks did not draw any faces on their court cards (since depicting faces in art is forbidden in Islam). The Europeans did not have this issue, and adapted the Muslim court cards of malik (king), malik na’ib (deputy king), and thani na’ib (second deputy) to king, queen, and prince or knight (“jack”). In 16th century France, the four kings were depicted as particular historical figures: the King of Spades was King David, the King of Clubs was Alexander the Great, the King of Hearts was Charlemagne, and the King of Diamonds was Julius (or Augustus) Caesar.