This week’s parasha, Bo, relays the commandment to the Children of Israel to prepare the Pesach offering. We are told that no one uncircumcised is permitted to consume of it (Exodus 12:48), from which we learn that many of the Israelites circumcised themselves in the days leading up to the Exodus. In fact, the Zohar (II, 35b-36a) points out on the words “and God shall pass over the opening” (12:23) that “the opening”, petach, is alluding to the opening of the reproductive organ! And thus, the Zohar says, “The blood was of two kinds, that of circumcision and that of the Passover lamb—the former symbolizing mercy and the latter justice.”

This week’s parasha, Bo, relays the commandment to the Children of Israel to prepare the Pesach offering. We are told that no one uncircumcised is permitted to consume of it (Exodus 12:48), from which we learn that many of the Israelites circumcised themselves in the days leading up to the Exodus. In fact, the Zohar (II, 35b-36a) points out on the words “and God shall pass over the opening” (12:23) that “the opening”, petach, is alluding to the opening of the reproductive organ! And thus, the Zohar says, “The blood was of two kinds, that of circumcision and that of the Passover lamb—the former symbolizing mercy and the latter justice.”

These two mitzvot are actually deeply connected. In fact, there are 36 commandments in the Torah for which their violation incurs karet, “excision” from the nation of Israel, and presumably from the World to Come (see Keritot 1:1). Of those 36, all are prohibitions that must not be violated, except for only two which are positive commandments requiring fulfilment: pesach and milah. Our Sages taught that the fulfilment of these two critical mitzvot not only prevents karet, but actually guarantees a Jew to earn their place in the World to Come! (For women who, of course, need no milah, they are considered to be “born circumcised” automatically, so it’s even easier. See Avodah Zarah 27a.)

Today, we are unable to bring the Pesach offering literally, but we fulfil the mitzvah through the Pesach seder. Thus, the Zohar says that “a person who speaks of the Exodus from Egypt and relays that story in joy is destined to rejoice with the Shekhinah in the World to Come”. The Haggadah itself tells us that anyone who participates in the seder joyously and speaks of the Exodus at length is praiseworthy, and the Zohar (II, 40b) adds that such a person thereby earns their share in Olam haBa, the World to Come.

Similarly, the Talmud (Eruvin 19a) relays that the simple status of being circumcised saves one from punishment in Gehinnom, with only one exception:

As Reish Lakish said: With regard to the sinners of Israel, the fire of Gehinnom has no power over them, as may be learned by a fortiori from the golden altar. If the golden altar in the Temple, which was only covered by gold the thickness of a golden dinar, stood for many years and the fire did not burn it, so too the sinners of Israel, who are filled with good deeds like a pomegranate, as it is stated: “Your temples [rakatekh] are like a split pomegranate” (Song of Songs 6:7), will not be affected by the fire of Gehinnom. And Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish said about this: Do not read: “Your temples [rakatekh]”, but rather: “Your empty ones [reikateikh]”, ie. even the sinners among you are full of mitzvot like a pomegranate; so how much more so [the fire of Gehinnom has no power over them].

But what about that which is written: “Those who pass through the valley of weeping”? (Psalms 84:7) There it speaks of those who are liable for punishment in Gehinnom, but our forefather Abraham comes and raises them up and receives them, except for a Jew who had relations with a gentile woman, for which his foreskin is redrawn, and our father Abraham does not recognize him [as one of his descendants].

Every single Jew, even a rebellious sinner, is saved by Abraham from Gehinnom—as long as the Jew is circumcised. However, a Jewish man who slept with a Gentile loses his “circumcised” status and Abraham does not recognize him as being part of his Covenant. This is not because there is anything wrong with a Gentile, for all human beings were made in God’s image and are precious to Hashem (Sanhedrin 37a). In fact, the Midrash attests in multiple places (including Yalkut Shimoni II, 42 and Tanna d’Vei Eliyahu Rabba 9:1) that “I bring Heaven and Earth to bear witness, whether one is a Gentile or a Jew, man or woman, slave or maid, anyone can merit to have the Divine Spirit rest upon them—all depending on their deeds.” Rather, the Torah has an explicit prohibition for Israel not to intermarry or be promiscuous with Gentiles for several good reasons, including the simple fact of it being a spiritual mismatch.

Now, why does the Talmud above specifically mention a man being intimate with a Gentile, and not a woman? One answer is as follows: If a Jewish man intermarries with a non-Jewish woman, the children are not Jewish, but if a Jewish woman intermarries with a non-Jewish man, the children are still Jewish! Thus, the intermarriage of a Jewish man with a non-Jewish woman completely cuts off his line from the Jewish people and the nation of Israel, meaning that such a Jewish man has, in effect, excised himself from his people. On the contrary, the intermarriage of a Jewish woman with a non-Jewish man—although undoubtedly still forbidden and a violation of Torah law—nonetheless does not excise her progeny from Israel.

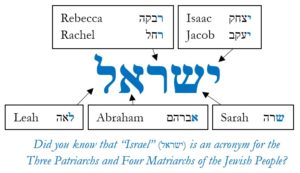

We must also remember that Abraham was the first to prohibit intermarriage, even before the Torah was given. Abraham instructed his servant Eliezer to go find a wife for his son Isaac from among his own people, and not the local Canaanites (Genesis 24:2-4). Moreover, Abraham was chosen by God and sealed a Covenant with Him because, as God Himself affirmed, “I know that he will instruct his children and his progeny to keep the way of God by doing what is just and right…” (Genesis 18:19) A Jewish man who does not follow the ways of Abraham and intermarries thus loses his connection to Abraham’s Covenant and to his people.

That said, there is always a chance to fix one’s errors. A Jewish man who intermarried need not divorce his wife, but should rather convert her and bring her into the nation of Israel. And a Jewish man who was with a non-Jewish woman in the past without marriage can repent and clear his record. In fact, the Talmud (Avodah Zarah 17a) tells the story of the infamous Elazar ben Durdaya, who went out of his way to sleep with every harlot, but ultimately recognized his sins and repented wholeheartedly—so much so that he died in grief. A Heavenly Voice then resounded and declared that Elazar was welcome in the World to Come!

Genuine repentance allows a person to clear their record, and God promises that He will forgive a sincere repentant each year on Yom Kippur (Leviticus 16:30). What other things wipe away one’s sins and give a person a fresh start? Our Sages taught us many practices that can bring about complete atonement. One is keeping Shabbat: “Anyone who observes Shabbat properly according to its laws, even if he worshipped idols like the generation of Enosh, he is forgiven!” (Shabbat 118a-b) The Talmud adds here that one who eats three meals on Shabbat is spared from three punishments: the suffering in the era preceding Mashiach, the suffering of Gehinnom, and the suffering at the final apocalyptic war of Gog u’Magog.

Another mitzvah that atones for all of one’s past sins is getting married (Yevamot 63b, Talmud Yerushalmi, Bikkurim 3:3). The wedding day is seen as a “mini-Yom Kippur”, which is why some communities have a custom for the bride and groom to fast prior to their chuppah. This is true even for a second marriage or late marriage, as the Sages derive this teaching from Esau’s second (or third) marriage. The same Yerushalmi source says that a person who ascends a high position of leadership is forgiven all of their past sins as well. This includes one who is ordained as a rabbi, or one who becomes president or holds high office. The Ba’al haTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, c. 1269-1343) cites this in his commentary on the Torah (Exodus 21:19), and also notes that one who was gravely ill and recovered is forgiven for all of their sins. This is based on the Talmud which states that “a person who is gravely ill does not recover until all of his sins have been forgiven.” (Nedarim 41a)

Lastly, the Torah tells us that “His land atones for His people” (Deuteronomy 32:43). Our Sages derive from this that being buried in the land of Israel wipes away all of one’s sins (Ketubot 111a). This is a major reason for why many Jews seek to be buried in Israel, even if they lived their entire lives in the diaspora. (That said, there are those who held that this only works if a person also lived in Israel, and was not simply transported there just for burial.)

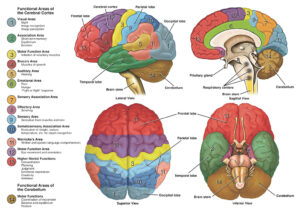

Finally, it’s important to mention that a person is only considered a full-fledged adult from age 20, and the sins one incurs before this age may certainly harm a person in this world, but are not tried by the Heavenly Court for Olam HaBa. (See Shabbat 89b; Zohar I, 118b; and Rashi on Numbers 16:27.) God knows that teenagers will make foolish mistakes—after all, He is the one that designed the human body to have all of those challenging hormonal changes. And He designed the brain in such a way that the decision-making and planning section, the pre-frontal cortex, is the last to fully develop. It is worth adding that the Midrash says Adam and Eve were created as twenty-year-olds (Beresheet Rabbah 14:7). Of course, this does not mean that someone who is currently under the age of 20 gets a free pass to sin! It is meant retroactively, for things one regrettably did in their youth.

Finally, it’s important to mention that a person is only considered a full-fledged adult from age 20, and the sins one incurs before this age may certainly harm a person in this world, but are not tried by the Heavenly Court for Olam HaBa. (See Shabbat 89b; Zohar I, 118b; and Rashi on Numbers 16:27.) God knows that teenagers will make foolish mistakes—after all, He is the one that designed the human body to have all of those challenging hormonal changes. And He designed the brain in such a way that the decision-making and planning section, the pre-frontal cortex, is the last to fully develop. It is worth adding that the Midrash says Adam and Eve were created as twenty-year-olds (Beresheet Rabbah 14:7). Of course, this does not mean that someone who is currently under the age of 20 gets a free pass to sin! It is meant retroactively, for things one regrettably did in their youth.

Guaranteed Olam HaBa

We saw above that one who engages joyously and actively at the Pesach seder is guaranteed a portion in the World to Come, as is one who is circumcised and was never promiscuous with a Gentile woman. What other mitzvot guarantee a person’s Olam haBa?

We saw above that one is forgiven for all of their sins if they keep Shabbat and if they are buried in Israel. The Talmud adds in another place (Pesachim 113a) that “Three people are among those who inherit the World to Come: One who lives in the Land of Israel; one who raises his sons to engage in Torah study; and one who recites Havdalah over wine at the conclusion of Shabbat.” Living in Israel is such a great mitzvah that a person automatically earns Olam HaBa. Reciting Havdalah regularly works the same magic. And then there’s putting one’s children through Jewish schools and ensuring that they engage in regular Torah study. After all, we say multiple times a day in the Shema that one should teach Torah to his children “in order that your days and your children’s days shall be prolonged upon the land which God promised your forefathers as long as the Heavens are upon the Earth.” (Deuteronomy 11:21) So, one who teaches Torah to his children will ultimately merit to inherit his promised portion for as long as the Heavens are upon the Earth.

Similarly, one who learns Torah is guaranteed a portion in the World to Come, as we say regularly in our prayers from Tana d’Vei Eliyahu that “Anyone who learns halakhot each day is guaranteed Olam haBa”. How many halakhot does one need to learn? The Mekhilta of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai says that “anyone who learns two halakhot in the morning and two halakhot in the evening, and works all day, it is as if he has fulfilled the whole Torah.” (16:4) So, even learning just a few verses each morning and evening is enough if done consistently. And it is worth repeating the famous first Mishnah in tractate Peah that “The following are the things for which a person enjoys the fruits in this world while the principal reward remains for him in the World to Come: Honoring one’s father and mother; acts of kindness; and making peace between a person and his friend—and the study of the Torah is equal to them all.”

Regular prayer also has tremendous benefits. The Talmud (Berakhot 16b) says that anyone who recites the Shema and prays the Amidah is guaranteed Olam haBa. The Zohar (III, 164a) adds that one who bows and stands upright during the Amidah will merit to stand upright at the Resurrection of the Dead. Reciting Ashrei (Psalm 145) three times a day also guarantees Olam haBa (Berakhot 4b). Even just answering “amen” to someone else’s blessing with intention earns one the World to Come! (Shabbat 119b) Meanwhile, the same passage says that answering amen, yehe sheme… in Kaddish with full intention wipes away all negative decrees upon a person, and clears even the stain of idolatry.

There are other super-powerful mitzvot, too. Giving regularly to charity is described by our Sages as being equal to all of the Torah’s other mitzvot combined, even if giving a small amount like a third of a shekel (Bava Batra 9a). The following page of Talmud says that giving charity saves one from Gehinnom, based on King Solomon’s famous adage that “charity saves from death.” (Proverbs 10:2) The Zohar (III, 273b, Ra’aya Mehemna) explains that a completely destitute person is considered “like dead” halakhically, so when one gives the destitute person charity, it’s as if he raised him from the dead. Thus, God will likewise resurrect the charitable person in Olam haBa, measure for measure.

Like charity, the Sages say that the mitzvah of tzitzit is equal to all the others combined. After all, we say in Shema multiple times a day that when one sees the tzitzit, he should be reminded of “all of God’s commands”. The Ba’al haTurim (on Numbers 15:38-39) points out that the value of this phrase (כל מצות ה’) equals 612, meaning that the one mitzvah of tzitzit is equal to the remaining 612! He further notes that the atbash transformation of tzitzit (המהמא) has a value of 91, like kis’i (כסאי), “My Throne”, and one who regularly fulfils the mitzvah of tzitzit “will merit to see the face of the Divine Presence” and be lifted up to Heaven on “the wings of eagles”.

Meanwhile, the Zohar (III, 253b, Ra’aya Mehemna) says that putting on tefillin in the morning is tied to King David’s words of lo amut ki echyeh, “I will not die, but live”, suggesting that one thereby merits eternal life. Lastly, the introductory verses of Perek Shirah, an ancient text recording the songs of all things in Creation, begin with Rabbi Eliezer the Great saying that “Anyone who involves himself with Perek Shirah in this world, merits saying it in the World to Come.” This is by no means an exhaustive list, and one could find other mitzvot, rituals, and texts that promise a guarantee of Olam haBa as well.

Finally, the Talmud (Sanhedrin 88b) says that one who has the following traits is destined for Olam HaBa: “One who is modest and humble, who bows and enters [the Synagogue or Beit Midrash] and bows and exits, who studies Torah regularly, and who does not take credit for himself.” This is reminiscent of the prophet Micah’s question: “What does God ask of you? Only to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God.” (Micah 6:8) The Sages say this was not just good advice, but a summary and condensation of all 613 commandments! (See Makkot 24a) The same page of Talmud says the prophet Amos reduced the whole Torah to the phrase “Seek Me and live!” (Amos 6:5), while the prophet Habakkuk reduced the whole Torah to the phrase “The righteous lives in his faith” (Habakkuk 2:4). Hillel famously taught that the whole Torah is “what is hateful to you don’t do unto others” (Shabbat 31a) and Rabbi Akiva said that the most important Torah verse is “Love your fellow as yourself” (Sifra, Kedoshim 4:12). Finally, we learn in Pirkei Avot (3:10) that “One with whom people are pleased, God is pleased. But anyone with whom people are displeased, God is displeased.” The last word goes to the prophet Isaiah (60:21), who said: “And your people, all of them righteous, shall possess the land for all time; they are the shoot that I planted, My handiwork in which I glory.”

To summarize, one is guaranteed their portion in the World to Come if they fulfil any (and hopefully all) of the following:

- Actively and joyously participate in a Pesach seder (Zohar II, 40b)

- Regularly study Torah, even just a few verses a day (Tana d’Vei Eliyahu, Mekhilta d’Rashbi 16:4, Peah 1:1)

- Teach Torah to their children, or put them in Jewish schools (Pesachim 113a)

- Live in Israel (Pesachim 113a)

- Recite Havdalah regularly at the conclusion of Shabbat (Pesachim 113a)

- Recite daily the Shema and Amidah prayer (Berakhot 16b; Zohar III, 164a)

- Recite Ashrei (Psalm 145) three times a day (Berakhot 4b)

- Answer “amen” with intention (Shabbat 119b; Zohar III, 285a-b)

- Give regularly to charity (Bava Batra 9a-10a; Proverbs 10:2; Zohar III, 273b, Ra’aya Mehemna)

- Wear tzitzit, put on tefillin daily, and/or regularly review Perek Shirah

- Are modest, humble, and treat all others with respect and dignity (Sanhedrin 88b, Avot 3:10)

- Circumcised (for a man), as long as one did not intermarry or was promiscuous with Gentile women, and failed to repent for it (Eruvin 19a)

To summarize, one is forgiven for all of their sins if they do any of the following:

- Keep Shabbat properly (Shabbat 118b)

- Recover from a serious illness (Nedarim 41a)

- Ascend to a high position of leadership (TY Bikkurim 3:3)

- Get married (Yevamot 63b, TY Bikkurim 3:3)

- Answer amen, yehe sheme rabbah in Kaddish with intention (Shabbat 119b)

- Genuinely repent on Yom Kippur (Leviticus 16:30, Yoma 85b)

- Are buried in Israel (Deuteronomy 32:42, Ketubot 111a)

- Retroactively for sins before the age of 20 (Shabbat 89b; Zohar I, 118b)

For lots more information, sources, and analysis, see the recent class ‘Every Jew is a Tzadik’.