In this week’s double Torah portion (Acharei-Kedoshim) we read that “when you will have planted all manner of trees for food, its fruit shall be forbidden; three years shall it be forbidden to you, it shall not be eaten.” (Leviticus 19:23) This refers to the mitzvah of orlah, where a newly-planted tree must be left unharvested for its first three years. Seemingly based on this, a custom has developed to leave the hair of newborn boys uncut until age three. On or around the boy’s third birthday, a special celebration is held (called upsherin or halakeh), often with family and friends taking turns to cut a bit of the boy’s hair. Henceforth, the boy is encouraged to wear a kippah and tzitzit, and his formal Jewish education will begin. It is said that just as a tree needs the first three years to establish itself firmly in the ground before it can flourish and its fruit be used in divine service, so too does a child.

Lag B’Omer 1970 in Meron. Photo from Israel’s National Photo Collection

Indeed, the Torah makes a comparison between trees and humans in other places. Most famously, Deuteronomy 20:19 states that fruit trees should not be harmed during battle, “for is the tree of the field a man?” The tree is not an enemy combatant, so it should be left alone. Although the plain meaning of the verse is that the tree is not a man, an alternate way of reading it is that “man is a tree of the field”. Elsewhere, God compares the righteous man to a tree firmly rooted in the ground (Jeremiah 17:8), and in another place compares the entire Jewish nation to a tree (Isaiah 65:22).

Having said that, the custom of upsherin is essentially unknown in ancient Jewish sources. It is not mentioned anywhere in the Talmud, nor in any early halakhic codes, including the authoritative Shulchan Arukh of the 16th century. Where did this very recent practice originate?

Lag b’Omer and the Arizal

The first Jews to take up this custom were those living in Israel and surrounding lands under Arab Muslim dominion in the Middle Ages. We see that Sephardic Jews in Spain and Morocco did not have such a custom, nor did the Yemenite Jews. (In fact, Yemenite Jews did not even have a custom to abstain from haircuts during Sefirat HaOmer at all.) This is particularly relevant because the upsherin ceremony is often connected with the Sefirat HaOmer period, with many waiting until Lag b’Omer for their child’s first haircut, and taking the boy to the grave of Rashbi (Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai) in Meron for the special ceremony.

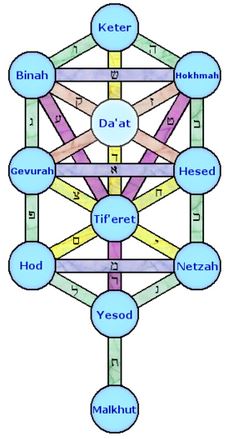

It appears that the earliest textual reference to upsherin is from Rabbi Chaim Vital (1543-1620), the primary disciple of the Arizal (Rabbi Isaac Luria, 1534-1572). Because of this, many believe that upsherin is a proper Kabbalistic custom that was instituted by, or at least sanctioned by, the great Arizal. In reality, the text in question says no such thing. The passage (Sha’ar HaKavanot, Inyan HaPesach, Derush 12) states the following:

ענין מנהג שנהגו ישראל ללכת ביום ל”ג לעומר על קברי רשב”י ור”א בנו אשר קבורים בעיר מירון כנודע ואוכלים ושותי’ ושמחים שם אני ראיתי למוז”ל שהלך לשם פ”א ביום ל”ג לעומר הוא וכל אנשי ביתו וישב שם שלשה ימים ראשו’ של השבוע ההו’ וזה היה פעם הא’ שבא ממצרים אבל אין אני יודע אם אז היה בקי ויודע בחכמה הזו הנפלאה שהשיג אח”כ. והה”ר יונתן שאגי”ש העיד לי שבשנה הא’ קודם שהלכתי אני אצלו ללמוד עם מוז”ל שהוליך את בנו הקטן שם עם כל אנשי ביתו ושם גילחו את ראשו כמנהג הידוע ועשה שם יום משתה ושמחה

On the custom of Israel going on Lag b’Omer to the grave of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and Rabbi Elazar his son (who are buried in the town of Meron as is known) and to eat and drink and rejoice there—I saw that my teacher, of blessed memory [the Arizal], that he went there once on Lag b’Omer with his whole family and remained there for three days, until the start of the sixth week [of the Omer]. And this was that one time, when he came from Egypt, but I do not know if he was then knowledgeable in this wisdom that he would later attain. And Rav Yonatan Sagis related to me that in the first year before I went to him to learn with my teacher of blessed memory, he took his small son with his whole family and there they cut his hair according to the known custom, and he held a feast and celebration there.

First, what we see in this passage is that the Arizal apparently only visited Meron on Lag b’Omer once, when he just made aliyah from Egypt, and before he had become the pre-eminent Kabbalist in Tzfat. (Some say this was actually before he made aliyah, and was simply on a trip to Israel.) Lag b’Omer is the 5th day of the 5th week of the Omer, and the Arizal stayed there for the remainder of the fifth week. Rav Chaim Vital wonders whether the Arizal was already an expert mystic at the time or not. Once he became the leader of the Tzfat Kabbalists, the Arizal apparently never made it a point to pilgrimage to Meron on Lag b’Omer. Rabbi Vital notes just that one time in the past, and it almost seems like once the Arizal was a master mystic, he understood there was nothing particularly mystical about it. In any case, nothing is said here of cutting hair.

The next part of the passage is more problematic. To start, it is unclear whether Rabbi Vital means that he and the Arizal went to study with Rav Yonatan Sagis, or that he and Rav Sagis went to study with the Arizal. We know that Rabbis Sagis and Vital were later both students of the Ari. However, when the Ari first came to Tzfat he was essentially unknown, and was briefly a disciple of other Kabbalists, namely the Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570). In fact, the Arizal only spent a couple of years in Tzfat before suddenly passing away at a very young age. Whatever the case, it is unclear from the passage whether it was the Arizal or Rav Sagis who was the one to take his son for a haircut on Lag b’Omer. Based on the context, it would appear that it was Rav Sagis who did so, not the Arizal, since we already learned that the Arizal did not make it a point to pilgrimage to Meron.

The nail on the coffin may come from an earlier passage in the same section of Sha’ar HaKavanot, where we read:

ענין הגילוח במ”ט ימים אלו לא היה מוז”ל מגלח ראשו אלא בערב פסח ובערב חג השבועות ולא היה מגלח לא ביום ר”ח אייר ולא ביום ל”ג לעומר בשום אופן

On the matter of shaving during these forty-nine days [of the Omer], my teacher of blessed memory did not shave his head [hair], except for the evening of Passover and the evening of Shavuot, and would not shave his hair at all [in between], not on Rosh Chodesh Iyar, and not on Lag b’Omer.

According to the Arizal, one should not shave at all during the entire Omer period, including Lag b’Omer! If that’s the case, then the Ari certainly wouldn’t take his child to Meron for a haircutting on Lag b’Omer. It must be that the previous passage is referring to Rav Sagis. Nowhere else in the vast teachings of the Arizal is the custom of waiting until a boy’s third birthday (whether on Lag b’Omer or not) mentioned. Thus, the Arizal was not the custom’s originator, did not expound upon it, and most likely did not even observe it.

So where did it come from?

A Far-Eastern Custom

While no ancient Jewish mystical or halakhic text before the 17th century appears to mention upsherin, a similar custom is discussed in much older non-Jewish sources. The Kalpa Sutras of the ancient Hindu Vedic schools speak of a ceremony called Chudakarana or Mundana, literally “haircutting”. It is supposed to be done before a child turns three, usually at a Hindu temple. It is explained that the hair a child is born with it connected to their past life, and all the negative things which that may entail. Removing this hair is symbolic of leaving the past life behind and starting anew. Interestingly, a small lock of hair is usually left behind, called a sikha, “flame” or “ray of light”, as a sign of devotion to the divine. This is surprisingly similar to the Chassidic custom of leaving behind the long peyos at the upsherin.

Hindu Sikha and Chassidic Peyos

From India, the custom seemingly moved across Asia to Arabia. One Muslim tradition called Aqiqah requires shaving the head of a newborn. Of this practice, Muhammad had apparently stated that “sacrifice is made for him on the seventh day, his head is shaved, and a name is given him.” An alternate practice had Muslims take their boys to the graves of various holy people for their first haircut. The Arabic for “haircut” is halaqah, which is precisely what the Mizrachi Jews of Israel called upsherin. Thus, it appears that Jews in Muslim lands adopted the custom from their neighbours. However, many of them waited not until the child is three, but five, which is when the Mishnah (Avot 5:22) says a child must start learning Torah. (In this case, the practice has nothing to do with the mitzvah of orlah or any connection to a sapling.)

In the early 19th century, Rabbi Yehudah Leibush Horenstein made aliyah to Israel and first encountered this practice of “the Sephardim in Jerusalem… something unknown to the Jews in Europe.” He was a Hasid, and in that time period many more Hasidim were migrating to Israel—a trend instigated by Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk (c. 1730-1788), the foremost student of the Maggid of Mezeritch (Rabbi Dov Ber, d. 1772), who in turn was the foremost student of the Baal Shem Tov (Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, 1698-1760) the founder of Hasidism. These hasidim in Israel adopted the practice from the local Sephardim, and spread it to the rest of the Hasidic world over the past century and a half.

While it has become more popular in recent decades, and has been adopted by other streams within Orthodoxy, and even many secular Israelis and Jews, upsherin is far from universally accepted. The Steipler (Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky, 1899-1985) was particularly upset about this practice (see Orchos Rabbeinu, Vol. I, pg. 233). When a child was brought before Rav Yitzchok Zev Soloveitchik of Brisk (1886-1959) for an upsherin, he frustratingly replied: “I am not a barber.” Other than the fact that it is not an established or widespread Jewish custom, there is a serious issue of it being in the category of darkei Emori, referring to various non-Jewish (and potentially idolatrous) practices.

Not So Fast

While there is no mention of the upsherin that we know today in ancient Jewish mystical or halakhic texts, there is mention of something very much related. In one of his responsa, the great Radbaz (Rabbi David ibn Zimra, c. 1479-1573) speaks of a practice where some people take upon themselves a “vow to shave their son in the resting place of Samuel the Prophet” (see She’elot v’Teshuvot haRadbaz, siman 608).

Recall that Samuel was born after the heartfelt prayer of his mother Hannah who was barren for many years. She came to the Holy Tabernacle in Shiloh and vowed that if God gave her a son, she would dedicate him to divine service from his very birth, and he would be a nazir his entire life (I Samuel 1:11). This means that he would never be allowed to shave or trim the hair of his head, just as the Torah instructs for anyone taking on a nazirite vow. There is something particularly holy about this, and we see earlier in Scripture how an angel comes to declare the birth of the judge Samson and instructs the parents to ensure he would be a nazirite for life, and that no blade ever come upon his head (Judges 13:5).

The Tanakh goes on to state that once Samuel was weaned, Hannah took him to the Tabernacle and left him in the care of the holy priests so that he could serve God his entire life. How old was he when he was weaned? While it doesn’t say so here, there is an earlier case where the Torah speaks of a child being weaned. This is in Genesis 21:8, where we read how Abraham through a great feast upon the weaning of his son Isaac. Rashi comments here (drawing from the Midrash and Talmud) that Isaac was two years old at the time. For this reason, many Hasidic groups actually perform the upsherin at age two, not three.

Back to the Radbaz, he was born in Spain but was exiled with his family in the Expulsion of 1492. The family settled in Tzfat, where the Radbaz was tutored by Rabbi Yosef Saragossi, the holy “White Saint” credited with transforming Tzfat from a small town of 300 unlearned Jews to a holy Jewish metropolis and the capital of Kabbalistic learning. In adulthood, the Radbaz settled in Fes, Egypt and his fame as a tremendous scholar and posek spread quickly. In 1517, he moved to Cairo and was appointed Hakham Bashi, the Chief Rabbi of Egypt. There, he founded a world-class yeshiva that attracted many scholars. Coming full circle, it was here in the yeshiva of the Radbaz that the Arizal began his scholarly career. In the last years of his life, the Radbaz wished to return to the Holy Land, and made his way back to Tzfat. It is possible that the Arizal left Egypt for Tzfat in the footsteps of his former rosh yeshiva. Ironically, the Radbaz (who lived to age 94, or even 110 according to some sources) would outlive the Arizal (who died at just 38 years of age).

While neither the Arizal nor his old teacher the Radbaz discuss cutting a three-year-old’s hair in particular (or doing it at the tomb of Rashbi), the Radbaz does speak of a personal vow that one may take to cut their child’s hair at the tomb of Samuel the Prophet. This practice comes from emulating Hannah, who took a vow with regards to her son Samuel. Samuel went on to be compared in Scripture to Moses and Aaron (and the Sages say Moses and Aaron combined!) Of course, Hannah never cut her child’s hair at all, but perhaps there is something spiritual in treating the child like a nazirite until the child is “weaned”.

In any case, the question that the Radbaz was addressing is what one must do if they took up such a haircutting vow but are unable to fulfil it because the authorities prohibit Jews from going to the grave sites of their ancestors. From here, some scholars conclude that the Ottoman authorities at the time really must have prohibited Jews from going to the grave of Samuel, near Jerusalem. Thus, it is possible that those Jerusalem Jews who had a custom of going to Samuel’s grave decided to journey to another famous grave instead. Perhaps it was in these years of the early 16th century that the custom to go to Rashbi in Meron (instead of Shmuel near Jerusalem) evolved.

So, there may be something to the upsherin custom after all. Of course, we still don’t know when the practice of going to Samuel’s grave emerged. That appears to have been a local custom (or possibly not a custom at all, but a personal vow) of Jerusalem’s medieval Jewish community. It, too, may have been influenced by neighbouring Muslims who went to the graves of their saints to cut their children’s hair.

Whatever the case, we see that foundations of upsherin are not so clear-cut. Contrary to popular belief, it is neither a universally accepted Jewish custom, nor a mandatory halakhic requirement. It did not originate with the Arizal either, although we do see some basis for it in the writings of the Radbaz. For those who wish to uphold this custom, they have upon whom to rely, and should meditate foremost upon the holy figures of Hannah and Samuel, who appear to be the spiritual originators of this mysterious practice.

The above is an excerpt from Garments of Light, Volume Two. Get the book here!