This week’s parasha begins by stating: “And it will be, when you come to the land which Hashem, your God, gives you for an inheritance, and you possess it, and settle in it…” (Deuteronomy 26:1) The term “when you come”, ki tavo, appears at least three more times in Deuteronomy as a preface to various mitzvot. In fact, out of the 613 mitzvot of the Torah, nearly half are only possible to fulfil in the Holy Land. Judaism is completely inseparable from the land of Israel.

For this reason, when the First Temple was destroyed and the Jews were exiled for the first time, there was a deep confusion as to how Judaism would continue to be practiced, and a great fear that the Torah would simply not survive the catastrophe. After all, how could the Jews continue to keep the Torah in a foreign land? How could they continue to serve God without a Temple? Without a priesthood? Without the dozens of agricultural laws that are dependent upon farming in the Holy Land? Without the pilgrimage festivals, the tithes, and the first fruits?

The Sages and Prophets of the day, two-and-a-half thousand years ago, had a mission to preserve their ancient faith and practices. This is precisely what they did. They taught that we don’t necessarily need to give sacrifices anymore, for we can “pay the cows with our lips” (Hosea 14:3). Daily prayer was thus instituted in place of daily sacrifices. Similarly, they taught that we don’t necessarily need a physical Temple, for God Himself had stated that the Temple was nothing but a means to “dwell among you” (Exodus 25:8), and God’s Divine Presence, the Shekhinah, remains among us in exile.

The Talmud (Berakhot 55a) would later state how in lieu of the Temple altar, each person has their mealtable, and the Sages modelled much of the mealtable procedure on the Temple ritual. For example, just as the Kohanim would wash themselves before and after the sacrifices, we do netilat yadayim and mayim achronim before and after the meal. Just as each sacrifice had to be brought with salt (Leviticus 2:13), we dip the bread in salt before eating it. And just as the altar used to atone for us, the Talmud says, now the mealtable atones for us. (For more on the mealtable-altar connection, see Secrets of the Last Waters.)

Instead of making pilgrimages to Jerusalem for the Shalosh Regalim, the three major festivals were adapted with new types of celebrations, gatherings, and customs. Holy texts were collected and canonized. Charity replaced tithes; rabbis and scholars took the place of priests; and studying the Torah’s mitzvot (especially those that could no longer be done) became synonymous with actually fulfilling them. New holidays would be instituted (like Tisha b’Av and Purim), as would new mitzvot like reciting Hallel and lighting Shabbat candles. In these ways, Judaism not only survived, but thrived.

Still, it was impossible to forget God’s Promised Land. While Judaism could be adapted to the diaspora, no one could erase what the Torah stated: we must fulfill all of these mitzvot “when you come to the land which Hashem, your God, gives you for an inheritance, and you possess it, and settle in it…” Jews are meant to live by the Torah in Israel. It is our indigenous land, and our God-given inheritance. And God Himself told us that if we are righteous and live by His Word, we will merit to dwell in His most special territory, and if not, the land itself will “vomit” us out (Leviticus 18:28), as it does all of those who are impure.

It is amazing to see how history corroborates this incredible prophecy. For thousands of years, the Holy Land essentially lay desolate, save for small Jewish and non-Jewish communities here and there. No empire was able to hold onto this territory for long, and no foreign kingdom was able to establish itself in any kind of perpetuity or prosperity.

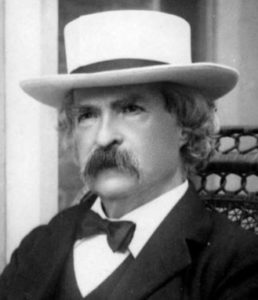

The Babylonians very quickly lost Israel to the Persians, and the Persians soon lost it to the Greeks. The Ptolemys and Seleucids fought over it unsuccessfully for decades until the Maccabees restored a prosperous Jewish kingdom. Their sins and infighting led to the Roman takeover of Israel. But the Romans, too, had an extremely hard time holding onto it. After the Romans destroyed the Second Temple, their fate was sealed as well. Their golden age was behind them, and Rome was henceforth on a steady decline. The Byzantines and Sassanids would fight over Israel back and forth until the Arabs took it. Then the various Arab caliphates fought over it, until the Crusaders decided it should be theirs. The Crusader era was one of indescribable violence and bloodshed, following which the Holy Land remained fallow for centuries. When Mark Twain visited in 1869, he wrote that it is a:

Mark Twain

desolate country whose soil is rich enough, but is given over wholly to weeds—a silent mournful expanse… A desolation is here that not even imagination can grace with the pomp of life and action… We never saw a human being on the whole route….There was hardly a tree or a shrub anywhere. Even the olive and the cactus, those fast friends of the worthless soil, had almost deserted the country… Of all the lands there are for dismal scenery, I think Palestine must be the prince… Can the curse of the Deity beautify a land? Palestine sits in sackcloth and ashes. Over it broods the spell of a curse that has withered its fields and fettered its energies. (The Innocents Abroad)

On that note, it is important to remember Twain’s account when dealing with Pro-Palestinians who falsely (and quite humorously) claim that Israel was full of Arabs when the Zionists arrived and “displaced” them. The historical reality, confirmed by accounts like Twain’s and other travellers, is that there was hardly “a human being” there. Ironically, the vast majority (though certainly not all) of “Palestinians” only came to settle in Israel when the Zionists arrived and created new prosperity and work opportunities. Occasionally, the Arabs admit this themselves, as did Fathi Hammad, Hamas’ Minister of the Interior, when he passionately spoke in a television address (see here) and said:

Brothers, half of the Palestinians are Egyptians and the other half are Saudis. Who are the Palestinians? Egyptian! They may be from Alexandria, from Cairo, from Dumietta, from the North, from Aswan, from Upper Egypt. We are Egyptians. We are Arabs.

Zuheir Moshan, the commander of the Palestinian Liberation Organization commander from 1971 to 1979, similarly said:

The Palestinian people does not exist. The creation of a Palestine state is only a means for continuing our struggle against the state of Israel for our Arab unity.

History makes it undoubtedly clear: Israel is the land of the Jews, for the Jews. No other nation has ever been successful in Israel except for the Jews. No other nation has ever established any lasting, flourishing presence there except for the Jews. Just as there was a vibrant Jewish kingdom in Israel three thousand years ago in the time of Solomon, there is a vibrant Jewish state there today.

It is important to keep in mind that the Torah clearly states that those who are impure—whether Jews or not—will be expelled from the Holy Land. We can therefore reason that those who do dwell in it securely are permitted to do so by the Land, which is not expelling them, and are its rightful inhabitants. Based on this, the great Rabbi Avraham Azulai (c. 1570-1643) wrote:

And you should know, every person who lives in the Land of Israel is considered a tzadik, including those who do not appear to be tzadikim. For if he was not righteous, the land would expel him, as it says “a land that vomits out its inhabitants.” (Leviticus 18:25) Since the land did not vomit him out, he is certainly righteous, even though he appears to be wicked. (Chessed L’Avraham, Ma’ayan 3, Nahar 12)

In this light, we can understand that even the most secular Zionists—who may appear to be “wicked” and “impure”—are still considered tzadikim in some way. With that lengthy preamble, let us try to understand the Zionist mindset and vision, and explore the true, little-known origins of Zionism.

A Religious Movement

It is commonly believed that Zionism essentially began as a movement of secular Ashkenazis in the late 1800s, with Theodor Herzl (wrongly) credited as the movement’s founder. The surprising reality is very different.

While it is hard to credit any one person with lighting the spark of Zionism, the best candidate is probably Rabbi Yehuda Bibas (1789-1852), the scion of a long line of illustrious Sephardic rabbis. Rabbi Bibas was the head of the renowned Gibralter yeshiva, and later the Chief Rabbi of Corfu, Greece. Throughout his travels across the Mediterranean, both in Southern Europe and North Africa, Rabbi Bibas witnessed constant persecutions of Jews. Regardless of whether Jews tried to fit in with mainstream society or not, or whether they were productive good citizens or not, the anti-Semitism would not abate.

Rabbi Bibas became convinced that the only solution is for Jews to return to their Biblical homeland and rebuild their kingdom. Like Mark Twain a couple of decades after him, Rabbi Bibas recognized that the land of Israel was lying fallow, accursed, devoid of inhabitants, and was ripe for Jewish resettlement. In 1839, he embarked on a world tour to convince Jews to make aliyah, and to gain support for a mass movement of Jewish settlement and nation-building.

Sir Moses Montefiore

Rabbi Bibas’ trip was funded by fellow Sephardic Jew Sir Moses Montefiore (1784-1885), who was born in Livorno, Italy, where Rabbi Bibas had studied in his youth. Montefiore became exceedingly wealthy in England, and later served as the Sheriff of London before being knighted by Queen Victoria. During his first trip to Israel in 1827, Montefiore was deeply touched and resolved to become a fully Torah-observant Jew. He established a Sephardic yeshiva, and built what is now the Montefiore Synagogue in Kent, England. He was known to bring a shochet with him on every trip to ensure he would have kosher meat. (A wealthy anti-Semite once told Montefiore that he had just returned from Japan, where there are “neither pigs nor Jews.” Montefiore replied: “Then you and I should go there, so that they should have a sample of each.”)

Montefiore made a total of seven trips to Israel, and like his friend Rabbi Bibas, was convinced that the Jews must return to their homeland and rebuild their nation-state. In fact, Montefiore laid the groundwork for the later Zionist movement. He paid for the construction of Israel’s first printing press and textile factory, rebuilt a number of synagogues and Jewish holy sites (including Rachel’s Tomb) and established several agricultural colonies. He commissioned censuses of the Holy Land’s population, which are still valuable to historians today (you can scan them here). His 1839 census of Jerusalem, for example, found that more than half of the city’s population were Sephardic Jews (over 3500 people). These statistics show that Jews were already the majority in much of the Holy Land, long before the Zionist movement officially began.

Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch Kalischer

One of Montefiore’s most vocal Ashkenazi supporters was Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer (1795-1874). Rabbi Kalischer was a student of the renowned Rabbis Akiva Eiger and Yakov Lisser, the Baal HaNetivot. Rabbi Kalischer saw firsthand the struggles that German and Eastern Europe Jews were living through. He was also frustrated by the abject poverty experienced by the Jews living in Israel. At that time, it was common for Jews to collect funds from the diaspora to send to their brothers in Israel. Rabbi Kalischer believed that Israel’s Jews must return to an agricultural life, and learn to cultivate the rich land on their own, so that they could become self-subsisting. He believed that the Jewish masses of Eastern Europe should go back to their homeland, too, where they would finally be safe from pogroms and expulsions.

In 1862, Rabbi Kalischer collected his ideas and plans in a book called Drishat Tzion. In this book he outlined, among other things, the need to build a Jewish agricultural school in Israel, and to create a Jewish military force to protect Israel’s inhabitants. He concluded that the salvation of the Jewish people, as prophesied in the Tanakh, would only come about when Jews start helping themselves instead of relying entirely on God and waiting passively. God is waiting for us to make the first move and show our deep yearning to return to our land, much like God had waited for Israel to make the first move at the Splitting of the Sea, as per the famous Midrash (see Nachshon ben Aminadav). Rabbi Kalischer’s activism was successful, and in 1870 the Mikveh Israel agricultural school was opened on a tract of land now within the boundaries of modern Tel-Aviv.

Rabbi Yehuda Alkali

Finally, the most influential proto-Zionist was Rabbi Yehuda Alkali (1798-1878), whom some scholars actually credit with being the true founder of Zionism. Rabbi Alkali studied under the great Sephardi kabbalists of Jerusalem, and went on to serve as a chief rabbi in Serbia. It was the 1840 Damascus Affair that inspired him to take up the cause of aliyah. That summer, 13 Jews in Damascus were arrested following a baseless blood libel accusation. Riots followed, resulting in attacks on Jews, the capture of 63 Jewish children, and the destruction of a synagogue. The imprisoned Jews were tortured to try to get them to confess. Four of the 13 Jews died during that torture, so it isn’t surprising that seven others ultimately “confessed” to the absurd crime.

The international community was aware of what was going on, and the story was covered by Western media. Many governments attempted to intervene and stop the madness. A Jewish delegation—led by Moses Montefiore—was sent to deliberate with the authorities in Damascus. They were ultimately successful, and the nine surviving Jewish prisoners were exonerated and freed.

Rabbi Alkali was horrified at these events, and saw how Christians and Muslims in Syria had conspired together against the Jews. This was the last straw for him. By a stroke of fate, he happened to meet Rabbi Bibas right around this time. The conclusion was obvious: the Jews must have a strong state of their own. There was no other way to prevent the ludicrous, unceasing anti-Semitism and persecution of Jews. That same year Rabbi Alkali established the Society for the Settlement of Eretz Yisrael. It was 1840, or 5600 on the Hebrew calendar, precisely the year that the Zohar prophesied to be the start of the Redemption (see ‘The Zohar’s Prophecy of Another Great Flood’ in Garments of Light).

Incredibly, Rabbi Alkali made a prophecy of his own based on the words of the Zohar: that the Jews have exactly one hundred years to bring about the Redemption. If Jews do not take on this challenge, he warned, then God would bring about the Redemption anyway, but through much more difficult means, through “an outpouring of wrath”. Of course, this is exactly what had happened one hundred years later.

In 1857, Rabbi Alkali published Goral L’Adonai (named after the Biblical lots—goral in Hebrew—that the Israelites cast before settling the Holy Land). This was a step-by-step manual for how to re-establish a Jewish state in Israel. In it, he proposed the resurrection of Hebrew as the spoken language of all Jews, the piece-by-piece purchase of the Holy Land from the Ottomans, and the necessity of the Jews to return to an agrarian lifestyle and work their own land. All of these would, of course, materialize in the coming decades.

It is with this book of Rabbi Alkali that the Zionist story comes full circle. Rabbi Alkali was the chief rabbi of the town of Semlin in Serbia. One of the congregants of his Semlin synagogue was a man named Simon Loeb Herzl, a dear friend of his. Rabbi Alkali presented one of the first copies of Goral L’Adonai to him. Three years later, Simon Loeb Herzl welcomed a new grandson: Theodor. It was in his grandfather’s study that a young Theodor Herzl came across Goral L’Adonai, and it was this work, scholars now conclude, that planted the seeds of Zionism in his mind.

By that point, the foundations of the Jewish State had already been laid by Rabbis Alkali and Bibas, by Moses Montefiore, and by the many that they had inspired, including Rabbi Kalischer. And so, Zionism did not begin as a secular Ashkenazi movement at all, and instead began, quite ironically, as a religious Sephardi movement. Of course, it was the Ashkenazis that took the movement to the next level, and without that great push the Jewish State would not have materialized.

This brings to mind an old Jewish idea: we see a pattern in the Tanakh based on the interplay between the children of Rachel and Leah. Back in ancient Egypt, it was Joseph (a child of Rachel) that set the stage for Israel to come down there. And it was Yehudah (a child of Leah) that then took the reins of leadership to bring the family together, and ensure their successful settlement in the land. Several centuries later, it was Joshua (a descendent of Rachel) that led the way to conquer the Holy Land. But it was only Othniel (of Yehudah, a descendant of Leah) that completed the resettlement. Later still, when Israel’s monarchy was established, it was Saul (a Benjaminite descendant of Rachel) who was the first king, and laid the framework for a Jewish kingdom, before David (of Leah, of course) unified all the tribes and established an everlasting dynasty. The same is said for the future messiah, who is said to come within two figures (or two phases): first Mashiach ben Yosef (of Rachel), then Mashiach ben David (of Leah).

It has been said that Sephardis are the descendants of Rachel (from the tribe of Joseph), while Ashkenazis are the descendants of Leah (from the tribe of Judah)—not biologically, of course, for we all come from the same singular Judean lineage, but perhaps spiritually. Not surprisingly then, when it comes to the Jewish State, the children of Rachel set the foundations, as they always do, before the children of Leah complete the process. Some believe this is the meaning of the famous prophecy in Ezekiel 37:15-21:

And the word of Hashem came to me, saying: “And you, son of man, take one stick, and write upon it: ‘For Judah, and for the children of Israel his companions’; then take another stick, and write upon it: ‘For Joseph, the stick of Ephraim, and of all the house of Israel his companions’; and join them one to another into one stick, that they may become one in your hand. And when the children of your people shall speak to you, saying: ‘Will you not tell us what you mean by these?’ Say to them: ‘Thus says the Lord God: Behold, I will take the stick of Joseph, which is in the hand of Ephraim, and the tribes of Israel his companions; and I will put them unto him together with the stick of Judah, and make them one stick, and they shall be one in My hand.’ And the sticks upon which you have written shall be in your hand before their eyes. And say to them: ‘Thus says the Lord God: Behold, I will take the children of Israel from among the nations, wherever they have gone, and will gather them on every side, and bring them into their own land…’”

Redeeming Zionism

We began this journey with the verse in this week’s parasha which suggests that the Torah can only really be fulfilled in Israel. The Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, 1194-1270) spoke of this explicitly (in his Discourse on Rosh Hashanah), and went so far as to suggest that keeping the mitzvot in the diaspora is only practice for when we can properly keep them in our Promised Land. At that point, it will be possible to fulfil all the mitzvot, and we will restore a more Biblical style of Judaism. Similarly, numerous Midrashic and Kabbalistic texts speak of a future time when Judaism will not be practiced as it is today, but will either revert to its Biblical style, or an even more primordial variety, or evolve to a completely new phase, or a combination of these. (See, for example, Vayikra Rabbah 13:3; Kohelet Rabbah 11:12; Yalkut Shimoni, Isaiah 429; Midrash Tehillim 146:4; Raya Mehemna on Nasso, 124b-125a)

This brings us back to Zionism. The interesting thing about those later, secular Zionists is not that they wanted to abandon all religion and have an entirely secular state (though some certainly wanted this), but that they wanted to restore a more Biblical style of Judaism. They sought to rid of the weak, diaspora Jew and replace him with the strong, ancient Israelite as described in Tanakh: a land-owner, a farmer, a warrior. This is why study of Tanakh was actually considered very important among many Zionists. It is known that David Ben-Gurion had a passionate Tanakh study group, and he even wrote a Tanakh commentary! Professor Nili Wazana argues that the aim of the Zionists was to replace the “diaspora literature” of the yeshivas with the ancient Scriptures of Israel, and to make the Tanakh the sole religious text of the Jewish State.

Of course, this is highly flawed thinking, for that “diaspora literature” is precisely what brings the Tanakh to life, and makes sense of it all. The secular Zionists were wrong about this one for sure. The idea here is only to highlight that the majority of Zionists had no intention of destroying Judaism, as some believe, but rather sought (perhaps naively) to restore a more ancient type of Judaism. Even the ultra-secular Herzl, in his Altneuland, dreams of a reconstructed Third Temple in Jerusalem. He describes in his vision (Book V, Ch. I) how

Throngs of worshipers wended their way to the Temple and to the many synagogues in the Old City and the New, there to pray to the God whose banner Israel had borne throughout the world for thousands of years.

Unfortunately, Zionism went on to take a very secular turn. While Herzl had no problem speaking of God, the composers of Israel’s Declaration of Independence didn’t want to explicitly mention Him. (They ultimately conceded to the more religious voices and included mention of the “Rock of Israel”.) This variety of atheistic, ultra-secular Zionism simply cannot work. Zionism without God is doomed to fail, and there are those who argue it already has.

Rav Kook

The only way to ensure the survival and success of Israel is through religious Zionism—which is how it was always intended by its earliest founders, those great rabbis that are sadly so little-known today. Rav Avraham Itzchak Kook (1865-1935), possibly the most well-known religious Zionist rabbi, believed that it was the holy work of these sages—along with others like the Vilna Gaon and multiple Chassidic rebbes who encouraged their disciples to make aliyah long before—that set the spiritual wheels in motion for Zionism:

… the lofty righteous of previous generations ignited a holy inner fire, a burning love for the holiness of Eretz Yisrael in the hearts of God’s people. Due to their efforts, individuals gathered in the desolate land, until significant areas became a Garden of Eden, and a large and important community of the entire people of Israel has settled in our Holy Land.

… Recently, however, the pious and great scholars have gradually abandoned the enterprise of settling the Holy Land… This holy work has been appropriated by those lacking in [Torah] knowledge and good deeds… Nonetheless, we see that their dedication in deed and action is nourished from the initial efforts of true tzaddikim, who kindled the holy desire to rebuild the Holy Land and return our exiles there.

Rav Kook, too, believed that secular Zionism will fail unless we “energetically return it to its elevated source and combine it with the original holiness from which it emanates.”

This is the task at hand. The first stage of the Redemption has already been ushered in. Indeed, the Kabbalists always spoke of two phases to the Redemption. The Ramchal (Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato, 1707-1746) clearly elucidated these stages—Pekidah and Zechirah—in his Ma’amar HaGeulah (‘Discourse on the Redemption’). The source of this two-stage process may very well come from that same prophecy of Ezekiel cited earlier, part of the longer “End of Days” narrative commonly referred to as Gog u’Magog.

Ezekiel uses cryptic names to tell us that the villain “Gog” (who hails from the land of “Magog”, hence the name of the prophecy) will come upon Israel in the End of Days:

in the Last Years [he] shall come against the land that is brought back from the sword, that is gathered out of many peoples, against the mountains of Israel, which have been a continual waste; but it is brought forth out of the peoples, and they dwell securely… (Ezekiel 38:8)

It is precisely when the Jews already return to Israel, “back from the sword”—from a great catastrophe (the Holocaust)—“gathered out of many peoples”, returning to a Holy Land that had been a “continual waste”, as seen earlier, that the Gog narrative takes place. God further confirms that this will happen in “the day My people Israel settles securely, you shall know it.” (38:14) After the Jews have already firmly settled in Israel can the final End of Days sequence of events occur. Ezekiel goes on to describe a tremendous war that will forever change the whole world. Only after this will God finally bring all the Jews to settle peacefully in Israel:

Now will I bring back the captivity of Jacob, and have compassion upon the whole house of Israel; and I will be jealous for My holy name. And they shall bear their shame, and all their breach of faith which they have committed against Me, when they shall dwell safely in their land, and none shall make them afraid… neither will I hide My face any more from them; for I have poured out My spirit upon the house of Israel, says the Lord God. (Ezekiel 39:25-29)

These are the concluding words of the Gog u’Magog prophecy. What we clearly see is that many Jews already return to settle in Israel before the final calamity occurs, and only after this will come the complete Ingathering of the Exiles, when “the whole house of Israel” will return to the Holy Land. This time, “none shall make them afraid”, and God will never again “hide [His] face.”

Redemption comes in two phases: the initial, incomplete return of the Jews to Israel, followed by the Final Redemption when the process is complete. History confirms that we now stand between the first and second phase. Each person must do everything they can to prepare for the imminent conclusion. How do we do so? Rav Kook had a few suggestions. To paraphrase one of his famous quotes, we must study not only “the Talmud and the legal codes” but also aggadah and ethics, Kabbalah and Chassidut, science and “the knowledge of the world”. And it isn’t enough to work on our intellectual and spiritual heights, for we must be physically strong, too:

Our return will only succeed if it will be marked, along with its spiritual glory, by a physical return which will create healthy flesh and blood, strong and well-formed bodies, and a fiery spirit encased in powerful muscles.

We must live up to our name, and be not just Yakov, the quiet one who “sits in tents” (Genesis 25:27), but Israel, who “battles with God, and with great men, and prevails” (Genesis 32:29).