Judaism is famously built upon an “oral tradition”, or Oral Torah, that goes along with the Written Torah. The primary body of the Oral Torah is the Talmud. At the end of this week’s parasha, Mishpatim, the Torah states:

And Hashem said to Moses: “Ascend to Me on the mountain and be there, and I will give you the Tablets of Stone, and the Torah, and the mitzvah that I have written, that you may teach them…

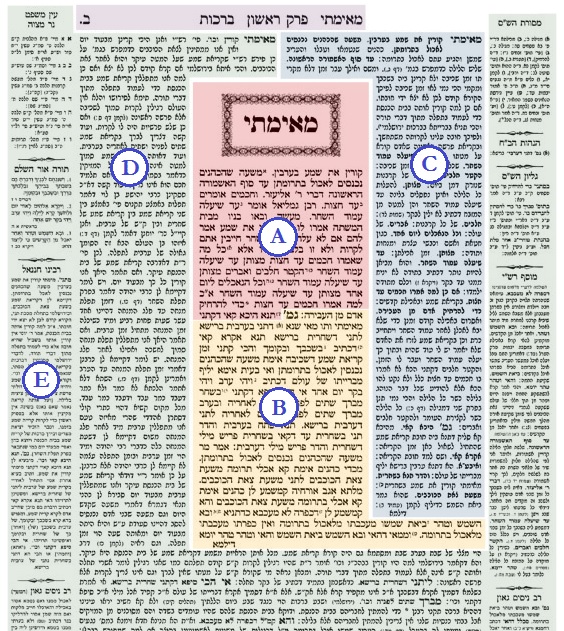

The Talmud (Berakhot 5a) comments on this that the “Tablets” refers to the Ten Commandments, the “Torah” refers to the Five Books of Moses, the “mitzvah” is the Mishnah, “that I have written” are the books of the Prophets and Holy Writings, and “that you may teach them” is the Talmud. The Mishnah is the major corpus of ancient Jewish oral law, and the Talmud, or Gemara, is essentially a commentary on the Mishnah, with a deeper exposition and derivation of its laws. Today, the Mishnah is printed together with the corresponding Gemara, along with multiple super-commentaries laid out all around the page, and this whole is typically referred to as “Talmud”.

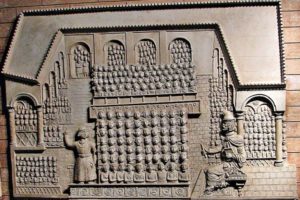

Anatomy of a page of Talmud: (A) Mishnah, (B) Gemara, (C) Commentary of Rashi, Rabbi Shlomo Itzchaki, 1040-1105, (D) Tosfot, a series of commentators following Rashi, (E) various additional commentaries around the edge of the page.

In the past, we’ve written how many have rejected the Talmud, starting with the ancient Sadducees, later the Karaites (whom some consider to be the spiritual descendants of the Sadducees), as well as the Samaritans, and many modern-day Jews whether secular or Reform. Such groups claim that either there was never such a thing as an “oral tradition” or “oral law”, or that the tradition is entirely man-made with no divine basis. Meanwhile, even in the Orthodox Jewish world there are those who are not quite sure what the Talmud truly is, and how its teachings should be regarded. It is therefore essential to explore the origins, development, importance, and necessity of the Talmud.

An Oral Torah

There are many ways to prove that there must be an oral tradition or Oral Torah. From the very beginning, we read in the Written Torah how God forged a covenant with Abraham, which passed down to Isaac, then Jacob, and so on. There is no mention of the patriarchs having any written text. These were oral teachings being passed down from one generation to the next.

Later, the Written Torah was given through the hand of Moses, yet many of its precepts are unclear. Numerous others do not seem to be relevant for all generations, and others still appear quite distasteful if taken literally. We have already written in the past that God did not intend for us to simply observe Torah law blindly and unquestioningly. (See ‘Do Jews Really Follow the Torah?’ in Garments of Light.) Rather, we are meant to toil in its words and extract its true meanings, evolve with it, and bring the Torah itself to life. The Torah is not a reference manual that sits on a shelf. It is likened to a living, breathing entity; a “tree of life for those who grasp it” (Proverbs 3:18).

Indeed, this is what Joshua commanded the nation: “This Torah shall not leave your mouth, and you shall meditate upon it day and night, so that you may observe to do like all that is written within it” (Joshua 1:8). Joshua did not say that we must literally observe all that is written in it (et kol hakatuv bo), but rather k’khol hakatuv bo, “like all that is written”, or similar to what is written there. We are not meant to simply memorize its laws and live by them, but rather to continuously discuss and debate the Torah, and meditate upon it day and night to derive fresh lessons from it.

Similarly, Exodus 34:27 states that “God said to Moses: ‘Write for yourself these words, for according to these words I have made a covenant with you and with Israel.’” Firstly, God told Moses to write the Torah for yourself, and would later remind that lo b’shamayim hi, the Torah “is not in Heaven” (Deuteronomy 30:12). It was given to us, for us to dwell upon and develop. Secondly, while the words above are translated as “according to these words”, the Hebrew is al pi hadevarim, literally “on the mouth”, which the Talmud says is a clear allusion to the Torah sh’be’al peh, the Oral Torah, literally “the Torah that is on the mouth”.

The Mishnah

2000-year old tefillin discovered in Qumran

It is evident that by the start of the Common Era, Jews living in the Holy Land observed a wide array of customs and laws which were not explicitly mentioned in the Torah, or at least not explained in the Torah. For example, tefillin was quite common, and they have been found in the Qumran caves alongside the Dead Sea Scrolls (produced by a fringe Jewish group, likely the Essenes) and are even mentioned in the New Testament. Yet, while the Torah mentions binding something upon one’s arm and between one’s eyes four times, it does not say what these things are or what they look like. Naturally, the Sadducees (like the Karaites) did not wear tefillin, and understood the verses metaphorically. At the same time, though, the Sadducees (and the Karaites and Samaritans) did have mezuzot. Paradoxically, they took one verse in the passage literally (Deuteronomy 6:9), but the adjoining verse in the same passage (Deuteronomy 6:8) metaphorically!

This is just one example of many. The reality is that an oral tradition outside of the Written Law is absolutely vital to Judaism. Indeed, most of those anti-oral law groups still do have oral traditions and customs of their own, just not to the same extent and authority of the Talmud.

Regardless, after the massive devastation wrought by the Romans upon Israel during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, many rabbis felt that the Oral Torah must be written down or else it might be lost. After the Bar Kochva Revolt (132-136 CE), the Talmud suggests there were less than a dozen genuine rabbis left in Israel. Judaism had to be rebuilt from the ashes. Shortly after, as soon as an opportunity presented itself, Rabbi Yehuda haNasi (who was very wealthy and well-connected) was able to put the Oral Torah into writing, likely with the assistance of fellow rabbis. The result is what is known as the Mishnah, and it was completed by about 200 CE.

The Mishnah is organized into six orders, which are further divided up into tractates. Zera’im (“Seeds”) is the first order, with 11 tractates mainly concerned with agricultural laws; followed by Mo’ed (holidays) with 12 tractates discussing Shabbat and festivals; Nashim (“Women”) with 7 tractates focusing on marriage; Nezikin (“Damages”) with 10 tractates of judicial and tort laws; Kodashim (holy things) with 11 tractates on ritual laws and offerings; and Tehorot (purities) with 12 tractates on cleanliness and ritual purity.

The root of the word “Mishnah” means to repeat, as it had been learned by recitation and repetition to commit the law to memory. Some have pointed out that Rabbi Yehuda haNasi may have used earlier Mishnahs compiled by Rabbi Akiva and one of his five remaining students, Rabbi Meir, who lived in the most difficult times of Roman persecution. Considering the circumstances of its composition, the Mishnah was written in short, terse language, with little to no explanation. It essentially presents only a set of laws, usually with multiple opinions on how each law should be fulfilled. To explain how the laws were derived from the Written Torah, and which opinions should be given precedence, another layer of text was necessary.

The Gemara

Rav Ashi teaching at the Sura Academy – a depiction from the Diaspora Museum in Tel Aviv

Gemara, from the Aramaic gamar, “to study” (like the Hebrew talmud), is that text which makes sense of the Mishnah. It was composed over the next three centuries, in two locations. Rabbis in the Holy Land produced the Talmud Yerushalmi, also known as the Jerusalem or Palestinian Talmud, while the Sages residing in Persia (centred in the former Babylonian territories) produced the Talmud Bavli, or the Babylonian Talmud. The Yerushalmi was unable to be completed as the persecutions in Israel reached their peak and the scholars could no longer continue their work. The Bavli was completed around 500, and its final composition is attributed to Ravina (Rav Avina bar Rav Huna), who concluded the process started by Rav Ashi (c. 352-427 CE) two generations earlier.

While incomplete, the Yerushalmi also has much more information on the agricultural laws, which were pertinent to those still living in Israel. In Persia, and for the majority of Jews living in the Diaspora, those agricultural laws were no longer relevant, so the Bavli does not have Gemaras on these Mishnaic tractates. Because the Yerushalmi was incomplete, and because it also discussed laws no longer necessary for most Jews, and because the Yerushalmi community was disbanded, it was ultimately the Talmud Bavli that became the dominant Gemara for the Jewish world. To this day, the Yerushalmi is generally only studied by those who already have a wide grasp of the Bavli.

The Talmud is far more than just an exposition on the Mishnah. It has both halachic (legal) and aggadic (literary or allegorical) aspects; contains discussions on ethics, history, mythology, prophecy, and mysticism; and speaks of other nations and religions, science, philosophy, economics, and just about everything else. It is a massive repository of wisdom, with a total of 2,711 double-sided pages (which is why the tractates are cited with a page number and side, for example Berakhot 2a or Shabbat 32b). This typically translates to about 6,200 normal pages in standard print format.

Placing the Talmud

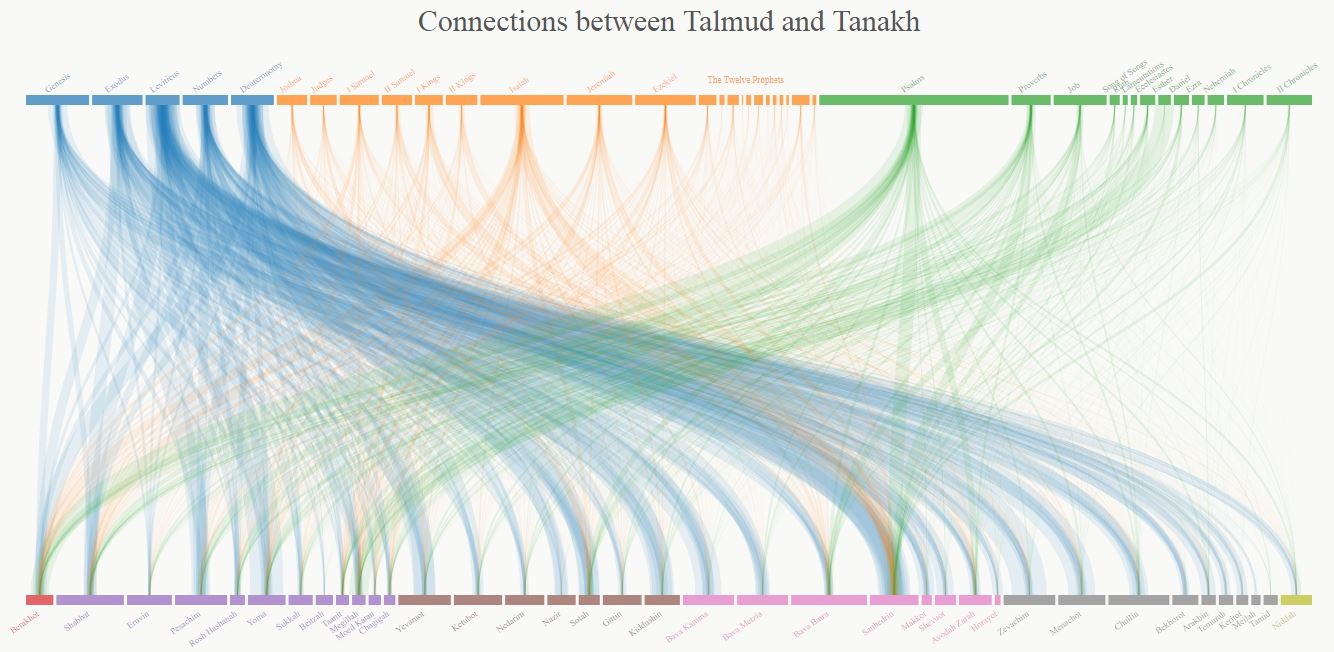

With so much information, it is easy to see why the Talmud went on to take such priority in Judaism. The Written Torah (the Tanakh as a whole) is quite short in comparison, and can be learned more quickly. It is important to remember that the Talmud did not replace the Tanakh, as many wrongly claim. The following graphic beautifully illustrates all of the Talmud’s citations to the Tanakh, and how the two are inseparable:

(Credit: Sefaria.org) It is said of the Vilna Gaon (Rabbi Eliyahu Kramer, 1720-1797) that past a certain age he only studied Tanakh, as he knew how to derive all of Judaism, including all of the Talmud, from it.

Indeed, it is difficult to properly grasp the entire Tanakh (which has its own host of apparent contradictions and perplexing passages) without the commentary of the Talmud. Once again, it is the Talmud that brings the Tanakh to life.

Partly because of this, Jews have been falsely accused in the past of abandoning Scripture in favour of the Talmud. This was a popular accusation among Christians in Europe. It is not without a grain of truth, for Ashkenazi Jews did tend to focus on Talmudic studies and less on other aspects of Judaism, Tanakh included. Meanwhile, the Sephardic Jewish world was known to be a bit better-rounded, incorporating more Scriptural, halachic, and philosophical study. Sephardic communities also tended to be more interested in mysticism, producing the bulk of early Kabbalistic literature. Ashkenazi communities eventually followed suit.

Ironically, so did many Christian groups, which eagerly embraced Jewish mysticism. Christian Knorr von Rosenroth (1636-1689) translated portions of the Zohar and Arizal into Latin, publishing the best-selling Kabbalah Denudata. Long before him, the Renaissance philosopher Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494), one of Michelangelo’s teachers, styled himself a “Christian Kabbalist”, as did the renowned scholar Johann Reuchlin (1455-1522). Meanwhile, Isaac Newton’s copy of the Zohar can be still found at Cambridge University. It is all the more ironic because Kabbalah itself is based on Talmudic principles, as derived from the Tanakh. For example, the central Kabbalistic concept of the Ten Sefirot is first mentioned in the Talmudic tractate of Chagigah (see page 12a), which also outlines the structure of the Heavenly realms. The Talmud is first to speak of the mystical study of Ma’aseh Beresheet (“Mysteries of Creation”) and Ma’aseh Merkavah (“Mysteries of the Divine Chariot”), of Sefer Yetzirah, of spiritual ascent, of how angels operate, and the mechanics of souls.

Having said all that, the Talmud is far from easy to navigate. While it contains vast riches of profound wisdom and divine information, it also has much that appears superfluous and sometimes outright boring. In fact, the Talmud (Sanhedrin 24a) itself admits that it is not called Talmud Bavli because it was composed in Babylon (since it really wasn’t) but because it is so mebulbal, “confused”, the root of Bavli, or Babel.

Of course, the Written Torah, too, at times appears superfluous, boring, or confused. The Midrash (another component of the Oral Torah) explains why: had the Torah been given in the correct order, with clear language, then anyone who read it would be “able to raise the dead and work miracles” (see Midrash Tehillim 3). The Torah—both Written and Oral—is put together in such a way that mastering it requires a lifetime of study, contemplation, and meditation. One must, as the sage Ben Bag Bag said (Avot 5:21), “turn it and turn it, for everything is in it; see through it, grow old with it, do not budge from it, for there is nothing better than it.”

Defending the Talmud

There is one more accusation commonly directed at the Talmud. This is that the Talmud contains racist or xenophobic language, or perhaps immoral directives, or that it has many flaws and inaccuracies, or that it contains demonology and sorcery. Putting aside deliberate mistranslations and lies (which the internet is full of), the truth is that, taken out of context, certain rare passages in the vastness of the Talmud may be read that way. Again, the same is true for the Written Torah itself, where Scripture also speaks of demons and sorcery, has occasional xenophobic overtones, apparent contradictions, or directives that we today recognize as immoral.

First of all, it is important that things are kept in their historical and textual context. Secondly, it is just as important to remember that the Talmud is not the code of Jewish law. (That would be the Shulchan Arukh, and others.) The Talmud presents many opinions, including non-Jewish sayings of various Roman figures, Greek philosophers, and Persian magi. Just because there is a certain strange statement in the Talmud does not mean that its origin is Jewish, and certainly does not mean that Jews necessarily subscribe to it. Even on matters of Jewish law and custom, multiple opinions are presented, most of which are ultimately rejected. The Talmud’s debates are like a transcript of a search for truth. False ideas will be encountered along the way. The Talmud presents them to us so that we can be aware of them, and learn from them.

First of all, it is important that things are kept in their historical and textual context. Secondly, it is just as important to remember that the Talmud is not the code of Jewish law. (That would be the Shulchan Arukh, and others.) The Talmud presents many opinions, including non-Jewish sayings of various Roman figures, Greek philosophers, and Persian magi. Just because there is a certain strange statement in the Talmud does not mean that its origin is Jewish, and certainly does not mean that Jews necessarily subscribe to it. Even on matters of Jewish law and custom, multiple opinions are presented, most of which are ultimately rejected. The Talmud’s debates are like a transcript of a search for truth. False ideas will be encountered along the way. The Talmud presents them to us so that we can be aware of them, and learn from them.

And yes, there are certain things in the Talmud—which are not based on the Torah itself—that may have become outdated and disproven. This is particularly the case with the Talmud’s scientific and medical knowledge. While much of this has incredibly stood the test of time and has been confirmed correct by modern science, there are others which we know today are inaccurate. This isn’t a new revelation. Long ago, Rav Sherira Gaon (c. 906-1006) stated that the Talmudic sages were not doctors, nor were they deriving medical remedies from the Torah. They were simply giving advice that was current at the time. The Rambam held the same (including Talmudic astronomy and mathematics under this category, see Moreh Nevuchim III, 14), as well as the Magen Avraham (Rabbi Avraham Gombiner, c. 1635-1682, on Orach Chaim 173:1) and Rav Shimshon Raphael Hirsch. One of the major medieval commentaries on the Talmud, Tosfot, admits that nature changes over time, which is why the Talmud’s science and medicine may not be accurate anymore. Nonetheless, there are those who maintain that we simply do not understand the Talmud properly—and this is probably true as well.

Whatever the case, the Talmud is an inseparable part of the Torah, and an integral aspect of Judaism. Possibly the greatest proof of its significance and divine nature is that it has kept the Jewish people alive and flourishing throughout the difficult centuries, while those who rejected the Oral Torah have mostly faded away. The Talmud remains among the most enigmatic texts of all time, and perhaps it is this mystique that brings some people to fear it. Thankfully, knowledge of the Talmud is growing around the world, and more people than ever before are taking an interest in, and benefitting from, its ancient wisdom.

A bestselling Korean book about the Talmud. Fascination with the Talmud is particularly strong in the Far East. A Japanese book subtitled “Secrets of the Talmud Scriptures” (written by Rabbi Marvin Tokayer in 1971) sold over half a million copies in that country, and was soon exported to China and South Korea. More recently, a Korean reverend founded the “Shema Education Institute” and published a six-volume set of “Korean Talmud”, with plans to translate it into Chinese and Hindi. A simplified “Talmud” digest book became a bestseller, leading Korea’s ambassador to Israel to declare in 2011 that every Korean home has one. With the Winter Olympics coming up in Korea, it is appropriate to mention that Korean star speed skater Lee Kyou-Hyuk said several years ago: “I read the Talmud every time I am going through a hard time. It helps to calm my mind.”

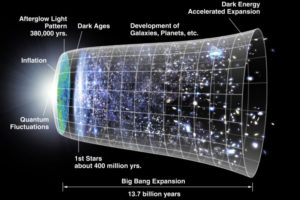

The evidence for a Big Bang is extensive. In fact, you can see some of it when you look at the “snow” on an old television that is not tuned to any channel. The antenna is picking up some of the cosmic microwave background radiation, the “afterglow” of the Big Bang. The entire universe is still glowing from that initial expansion! Popular physicist Brian Greene writes in his bestselling The Hidden Reality (pg. 43):

The evidence for a Big Bang is extensive. In fact, you can see some of it when you look at the “snow” on an old television that is not tuned to any channel. The antenna is picking up some of the cosmic microwave background radiation, the “afterglow” of the Big Bang. The entire universe is still glowing from that initial expansion! Popular physicist Brian Greene writes in his bestselling The Hidden Reality (pg. 43):