In this week’s parasha, Toldot, we are introduced to the twin sons of Isaac: Jacob and Esau. The Torah tells us that the boys grew up and Esau became a “man of the field” while Jacob was “an innocent man sitting in tents” (Genesis 25:27). In rabbinic literature, Esau takes on a very negative aura. Although the Torah doesn’t really portray him as such a bad guy, extra-Biblical texts depict him as the worst kind of person.

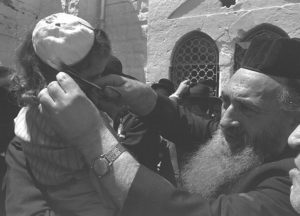

A 1728 Illustration of Esau selling his birthright.

Take, for instance, the first interaction between Jacob and Esau that the Torah relates. Esau comes back from the field extremely tired. At that moment, Jacob is cooking a stew. Esau asks his brother for some food, and Jacob demands in exchange that Esau give up his birthright (ie. his status as firstborn, and the privileges that come with that). Esau agrees because “behold, I am going to die” (Genesis 25:32). The plain text of the Torah makes it seem like Jacob took advantage of Esau’s near-fatal weariness and tricked him into selling his birthright. This is later confirmed when Esau says that Jacob had deceived him (Genesis 27:36), implying that Esau never really wished to rid of it.

Yet, the Torah commentaries appear to flip the story upside down. When Esau comes back from the field exhausted, it isn’t because he just returned from a difficult hunt, but rather because, as Rashi comments, he had just come back from committing murder! When Esau says “I am going to die”, it isn’t because he was on the verge of death at that moment, but because he didn’t care about the birthright at all, choosing to live by the old adage of “eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die”. This is a very different perspective on the same narrative.

Another example is when, many years later, Jacob returns to the Holy Land and Esau comes to meet him. Jacob assumes Esau wants to kill him, and prepares for battle. Instead, Esau genuinely seems to have missed his brother, and runs towards him, “embracing him, falling upon his neck, and kissing him” (Genesis 33:4). Again, some of the commentaries turn these words upside down, saying that Esau didn’t really lovingly kiss his brother, but actually bit him! Rashi’s commentary on this verse cites both versions. He concludes by citing Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai in stating that although Esau, as a rule, hates Jacob, at that moment he really did love his brother.

So, how bad was Esau really?

Seeing the Good in Esau

Occasionally, we read about Esau’s good qualities. The Midrash (Devarim Rabbah 1:15) famously states that no one honoured their parents better than Esau did. This is clear from a simple reading of the Torah, too, where Esau is always standing by to fulfil his parents’ wishes. For instance, as soon as he learns that his parents are unhappy with his choice of wives, he immediately goes off to marry someone they might approve of (Genesis 28:8-9).

We should be asking why his parents didn’t simply tell him from the start that his original wives were no good? Why did they allow him to marry them in the first place? If Esau really was the person who most honours his parents, he would have surely listened to them! We may learn from this that Esau’s parents didn’t put too much effort into him. It’s almost like Rebecca gave up on her son from the moment she heard the prophecy about the twins in her belly. The Torah says as much when it states, right after the birth of the twins, that “Isaac loved Esau because his game-meat was in his mouth, but Rebecca loved Jacob.” (Genesis 25:28) Rebecca showed affection to Jacob alone, while Isaac’s love for Esau was apparently conditional. Of course, children always feel their parents’ inner sentiments, and there is no doubt Esau felt his parents’ lack of concern for him. Is it any wonder he tried so hard to please them?

From this perspective, one starts to feel a great deal of pity for Esau. How can anyone read Esau’s heartfelt words after being tricked out of his blessing and not be filled with empathy?:

When Esau heard his father’s words, he cried out a great and bitter cry, and he said to his father, “Bless me, too, O my father! …Do you not have a blessing left for me?” (Genesis 27:34-36)

Esau was handed a bad deal right from the start. He was born different, not just in appearance, but with a serious life challenge. He was gifted (or cursed) with a particularly strong yetzer hara, from birth. His fate was already foretold, and his parents believed it. They invested little into him. And it seems all he ever wanted was to make them proud.

Incidentally, this is one of the major problems with fortune-telling, and why the Torah is so adamant about not consulting any kind of psychic. The psychic’s words, even if entirely wrong, will shape the person’s views. It is very much like the Talmud’s statement (Berakhot 55b) that a dream is fulfilled according to how it is interpreted. A person believes the interpreter, and inadvertently brings about that interpretation upon themselves. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Who knows what might have happened if Rebecca never bothered to consult a prophet about her pregnancy? After all, Jewish tradition is clear on the fact that negative prophecies do not have to come true. God relays such a prophecy in order to inspire people to change, and thus avert the negative decree. Such was precisely the case with Jonah and his prophecy regarding Nineveh. The people heard the warning, repented, and the prophecy was averted.

Perhaps this is what Isaac and Rebecca should have done. Instead of giving up on Esau, they should have worked extra hard to guide him in the right direction. (Isaac indirectly did the opposite, motivating his son’s hunting since he loved the “game-meat in his mouth”.) The Sages affirm that Esau was not a lost case, and state that had Jacob allowed his daughter Dinah to marry Esau, she would have reformed him (see, for example, Beresheet Rabbah 76:9).

At the end, Jacob returns to the Holy Land and, instead of the war with Esau that he was expecting, his brother welcomes him back with open arms. He weeps, and genuinely misses him. Esau has forgiven his brother, yet again, and buries the past. He hopes to live with his brother in peace henceforth, and invites him to live together in Seir. Esau offers to safely escort Jacob and his family. Jacob rejects the offer, and tells Esau to go along and he will join him later (Genesis 33:14). This never happens. Jacob has no intention to live with Esau, and as soon as his brother leaves, Jacob a completely different course. Esau is tricked one last time.

We only hear about Esau once more in the Torah. When Isaac dies, Esau is there to give his father a proper burial (Genesis 35:29). In fact, the Book of Jubilees, which doesn’t portray Esau too kindly either, nonetheless suggests that Esau had repented at the end of his life. There we read that it was his sons that turned evil, and even coerced him into wrongdoing (37:1-5). In Jubilees, Esau tells his parents that he has no interest in killing Jacob, and loves his brother wholeheartedly, more than anyone else (35:22). He admits that Jacob is the one that deserves the birthright, and a double portion as the assumed firstborn (36:12).

The Torah never tells us what ends up happening to Esau. The Midrash states that he was still there when Jacob’s sons came to bury their father in the Cave of the Patriarchs. Esau tried to stop them, at which point Jacob’s deaf grandson Hushim decapitated him. (A slightly different version is found in the Talmud as well, Sotah 13a.) Esau’s head rolled down into the Cave of the Patriarchs, while the rest of his body was buried elsewhere. Perhaps what this is meant to teach us is that while Esau’s body was indeed mired in sin, his head was completely sound, and he certainly had the potential to be a righteous man—maybe even one of the forefathers, hence his partial burial in the Cave of the Patriarchs.

At the end of the day, Esau is not so much a villain as he is a tragically failed hero.

Why Did Esau Become so Evil?

Esau meets Jacob, by Charles Foster (1897)

As we’ve seen, the Torah itself doesn’t portray Esau as such a bad person. Conversely, one of the 613 mitzvot is “not to despise an Edomite, for he is your brother.” (Deuteronomy 23:8) The Torah reminds us that the children of Israel and the children of Esau (known as Edomites) are siblings, and should treat each other as such.

Nearly a millennium later, the prophet Malachi—generally considered the last prophet and, according to one tradition, identified with Ezra the Scribe—says (Malachi 1:2-3):

“I have loved you,” says Hashem, “Yet you say: ‘How have You loved us?’ Was not Esau a brother to Jacob?” says Hashem, “yet I loved Jacob, but Esau I hated…”

The text goes on to differentiate between Israel and Edom, stating that while Israel will be restored, Edom will be permanently extinguished. We have seen this prophecy fulfilled in history; Israel is still here, of course, while Edom has long disappeared from the historical record. Jacob’s descendants continue to thrive, while Esau’s are long gone.

By the times of the Talmud, there were no real Edomites left, so the Sages began to associate Edom with a new entity: the Roman Empire. The Sages certainly didn’t believe that the Romans were the direct genetic descendants of Esau, but rather that they were their spiritual heirs. Why did the Sages make this connection?

I believe the answers lies with King Herod the Great.

Recall that approximately two thousand years ago Herod ruled as the Roman-approved puppet king of Judea. He was a tremendous tyrant, and is vilified in both Jewish and Christian tradition. The Talmud (Bava Batra 3b-4a) relates how Herod slaughtered all the rabbis in his day, leaving only Bava ben Buta, whom he had blinded. Later, Herod had an exchange with Bava and realized how wise the rabbis were:

Herod then said: “I am Herod. Had I known that the Rabbis were so circumspect, I should not have killed them. Now tell me what amends I can make.”

Bava ben Buta replied: “As you have extinguished the light of the world, [for so the Torah Sages are called] as it is written, ‘For the commandment is a light and the Torah a lamp’ (Proverbs 6:23), go now and attend to the light of the world [which is the Temple] as it is written, ‘And all the nations become enlightened by it.’” (Isaiah 2:2)

A model of Herod’s version of the Second Temple in Jerusalem

Herod did just that, and renovated the Temple to be the most beautiful building of all time, according to the Talmud. It wouldn’t last long, as that same Temple would be destroyed by his Roman overlords within about a century.

What many forget is that Herod was not a native Jew, but an Idumean. And “Idumea” was simply the Roman name for Edom. Herod was a real, red-blooded Edomite. (Though it should be noted that the Idumeans had loosely, or perhaps forcibly, converted to Judaism in the time of the Hasmoneans.) Herod took over the Jewish monarchy, and began the horrible persecutions that the Roman Empire—of which he was a part—was all too happy to continue. It seems quite likely, therefore, that the association between Edom and Rome began at that point. The people resented that Roman-Edomite tyrant Herod that persecuted them so harshly.

Henceforth, it was easy for the Sages to spill their wrath upon Edom, and their progenitor Esau. Esau became a symbol of the Roman oppressor. “Esau” and “Edom” were code words, used for speaking disparagingly about Rome to avoid alarming the authorities. Indeed, when the Sages speak about the evils of Esau, they are often really referring to the evils of the Roman Empire. It is therefore not surprising that Esau becomes possibly the most reviled figure in the Torah—as the Romans were unquestionably the most reviled entity in Talmudic times.

The above is an excerpt from Garments of Light, Volume Two. To continue reading, get the book here!