‘Elijah Taken Up to Heaven’

This week’s parasha is named after Pinchas, grandson of Aaron, who is commended for taking action during the sin with the Midianite women. Pinchas was blessed with an “eternal covenant”, and Jewish tradition holds that he never really died. Pinchas became Eliyahu, and as the Tanakh describes, Eliyahu was taken up to Heaven alive in a flaming chariot (II Kings 2). While we know what the name “Eliyahu” means, the name “Pinchas” is far more elusive. It doesn’t seem to have any meaning in Hebrew. Historical records show that there was a very similar name in ancient Egypt, “Pa-Nehasi”. Did Pinchas have a traditional Egyptian name?

When we look more closely, we find that multiple figures of the Exodus generation actually bore Egyptian names. For example, “Aaron” (or Aharon) doesn’t have a clear meaning in Hebrew, and appears to be adapted from the ancient Egyptian name “Aha-Rw”, meaning “warrior lion”. Even the origin of Moses’ name is not so clear.

Although the Torah tells us that Pharaoh’s daughter named him “Moshe” because she “drew him [meshitihu] from the water” (Exodus 2:10), it seems very unlikely that an Egyptian princess should know Hebrew so well and give her adopted child a Hebrew name. Our Sages noted this issue long ago, and grappled with the apparent problem. Chizkuni (Rabbi Hezekiah ben Manoach, c. 1250-1310) writes that it was actually Moses’ own mother Yocheved that named him “Moshe”, and then informed Pharaoh’s daughter of the name. Yet, the Midrash affirms that Yocheved called her son “Tuviah”, or just “Tov” (based on Exodus 2:2), and Moshe was the name given by Pharaoh’s daughter. Meanwhile, Ibn Ezra (Rabbi Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 1089-1167) suggests that Pharaoh’s daughter called him “Munius”. Josephus takes an alternate approach entirely, saying that Pharaoh’s daughter (whose name was Thermuthis, before she became a righteous convert and was called Batya or Bitya in Jewish tradition) named him Moses because the Egyptian word for water is mo.

The most elegant solution might be that Pharaoh’s daughter called him “Mose” (spelled the same way, but pronounced with a sin instead of shin), which means “son” in Egyptian. This is most fitting, since Pharaoh’s daughter yearned for a child of her own, and finally had a “son”. In fact, we see this suffix (and its close variant mses, from which the English “Moses” comes) used frequently in Egyptian names of that time period, such as Ahmose, Thutmose, and Ramses. Thus, he would have been known as Mose (or Moses) during his upbringing, but later known to his nation as Moshe, with a more appropriate and meaningful Hebrew etymology, yet without having to change the spelling of the name (משה) at all.

All of this begs the question: is it important to have a Hebrew name? And is it okay to have a Hebrew name together with an English name, or a name in the local language of wherever a Jew may live?

Why Are So Many Sages Called “Shimon”?

When looking through the names of the many rabbis in Talmudic and Midrashic literature, we find something quite intriguing. Although we would expect the Sages to be named after great Biblical figures like Moses, David, or Abraham, in reality there are essentially no sages with such names! Instead, we find a multitude of names of lesser-known Biblical figures, and many names that have no Biblical or Hebrew origin at all.

One very common name is Yochanan: There’s Yochanan ben Zakkai and Yochanan haSandlar, Yochanan bar Nafcha, Yochanan ben Nuri, and Yochanan ben Beroka. Another popular name is Yehoshua. While we might not expect this name to be so popular (considering its association with Jesus), we still find Yehoshua ben Perachia, Yehoshua ben Levi, Yehoshua ben Chananiah, Yehoshua ben Korchah, and many others. There are also lots and lots of Yehudas like Yehuda haNasi (and his descendents, Yehuda II and Yehuda III), Yehuda ben Beteira, Yehuda bar Ilai, and Yehuda ben Tabbai. And there are tons of Elazars: Elazar ben Arach, Elazar ben Azariah, Elazar ben Pedat, and many more with the similar “Eliezer”.

Perhaps the most common name is “Shimon”. There is Shimon haTzadik and Shimon bar Yochai, Shimon bar Abba and Shimon ben Shetach, Shimon ben Gamaliel (both I and II), Shimon ben Lakish (“Reish Lakish”), and more. We would think this is a strange choice, considering that the Biblical Shimon was actually of somewhat poor character (at least compared to the other sons of Jacob). In fact, on his deathbed, Jacob did not bless Shimon at all, and instead said he wanted nothing to do with his violent nature. Moses, meanwhile, completely omits Shimon in his last blessings! So why would so many of our Sages be called “Shimon”?

A Good-Sounding Name

What might explain the strange selection of names among our ancient Sages? While no clear reason stands out, there is one plausible answer. It appears that the choice of names above was heavily influenced by the contemporary Greek society. Just as today many Jewish parents seek Hebrew names that also sound good in English, it seems parents back then wanted names that sounded good in Greek (since most Jews lived in the Greek part of the Roman, and later “Byzantine”, Empire).

We find that Greek names tend to end with an “n”: Platon (Greek for “Plato”), Jason, and Solon, for example. Numerous others end with “s”: Aristotles (Greek for “Aristotle”), Pythagoras, Philippos. Indeed, many of our Sages actually have such Greek names directly: Yinon, Hyrcanus, Pappus, Symmachus, Teradyon, and Onkelos. There is no indication that these great rabbis had some other “Hebrew” name.

Those that did want to bear Hebrew names could choose names already ending with an “n” like Shimon and Yochanan. Or, they could choose names where adding an “s” to the end would be easy: Yehoshua in Greek is Yeosuos (later giving rise to Yesus, ie. Jesus), while Yehuda is Yudas (Judas). Such names would be easy to convert between Hebrew and Greek. We know from historical sources that several people named Chananiah were simultaneously called “Ananias” in Greek.

The same is true for Elazar or Eliezer. Many Greek names transliterated into English and other languages simple lose their “s” and end with an “r”: Antipatros becomes Antipater, while Alexandros becomes Alexander. In reverse fashion, Elazar could easily become Elazaros (or Lazarus)—very palatable in the Greek-speaking world which our early Sages inhabited.

On that note, what do we make of “Alexander”? A great number of Jews both modern and ancient (there is Alexander Yannai and Rabbi Alexandri in the Talmud) have this name. Some cite a famous Midrashic account of Alexander the Great’s arrival in Jerusalem as being proof that while Alexander is not a Hebrew name, it is something of an “honorary” Jewish name. This requires a more careful analysis.

Is Alexander a Jewish name?

The Talmud (Yoma 69a) describes Alexander the Great’s conquest of Judea. As he is marching towards Jerusalem, intent on destroying the Temple, Shimon HaTzadik goes out to meet him in his priestly garments (he was the kohen gadol at the time). When Alexander sees him, he halts, gets off his horse, and bows down to the priest. Alexander’s shocked generals ask why he would do such a thing, to which Alexander responds that he would see the face of Shimon before each successful battle. Alexander proceeds to treat the Jews kindly, and leaves the Temple intact. The Talmud stops there, though it does mention that this event took place on the 25th of Tevet, which was instituted as a minor holiday on which mourning was forbidden. (The story is also attested to by Josephus, though with a different high priest—see here for more.)

‘Alexander the Great and Jaddus the High Priest of Jerusalem’ by Pietro da Cortona (1596-1669)

According to one tradition, the priests at the time wanted to honour Alexander for his kindness, and named all the boys born that year “Alexander”. In another version, Alexander was given a tour of the Holy Temple and, naturally, wished to place a statue of himself inside. Since this was impossible (but they couldn’t refuse the emperor), Shimon haTzadik convinced him that it would be a greater honour for all the children born to be named “Alexander”. Either way, some like to say that “Alexander” has become a Jewish name ever since.

In truth, this suggestion looks more like a modern way of explaining why so many Jews were named Alexander. In reality, the Midrash clearly states that a Jew should not name his child Alexander. We read in Vayikra Rabbah 32:5:

In the merit of four things was Israel redeemed from Egypt: they did not change their names*, nor their language, they did not speak lashon hara, and not one among them committed sexually immoral sins… They did not call Yehuda “Rufus”, and not Reuben “Lullianus”, and not Yosef “Listus”, and not Benjamin “Alexander”…

Apparently, when Midrash Rabbah was composed—just like today—it was common for Jews to have a non-Jewish name that they would use regularly, together with a Hebrew name that they would use only in Jewish circles. The Hebrew name “Benjamin” was often paired with “Alexander”.

We see from the Midrash above that it is important to have a Hebrew or Jewish name. But what exactly counts as a “Jewish” name?

Non-Jewish “Jewish” Names

Although today most Jews insist on having Hebrew or Biblical names (and rightly so), it seems that our Sages weren’t so strict in this regard. Indeed, many of them bore Greek, Latin, or Aramaic names with no second Hebrew name. Akiva, Avtalyon, Nechunia, Mani, Nittai, Nehorai, Adda, Papa, Simlai, Tanhum, Tarfon, Ulla, and countless others are cited in rabbinic literature. As we saw earlier, those that did have Hebrew names naturally chose names that would be palatable to the surrounding Greeks, much like many Jews today choose names that have easy English homonyms.

This trend continued for centuries, all the way up to modern times. The result is that many seemingly “Jewish” names are actually adaptations of very non-Jewish names. For example, one popular name among Ashkenazi Jews in the past was Feivel or Feibush. This name, meaning “bright”, comes from Phoebus, one of the appellations for the Greco-Roman god of light, Apollo. With this in mind, there may actually be a big halachic problem of bearing this name, since it is forbidden to recite the names of idols. That said, the names Mordechai and Esther actually come from the Babylonian idols Marduk and Astarte, or Ishtar! Nonetheless, they became solid Jewish names, though this case is different because it comes with a clear source in Tanakh. Going back to Feivel, some say the name was only meant to substitute the Biblical name Shimshon, the root of which is “sun”, thus having a similar meaning to Phoebus or Apollo. Others link the name to Pavel, Paul, or Philipp, also not of Jewish origin.

Another appellation for Apollo was Lycegenes or Lukegenes, “born of a wolf” (possibly the source of the name “Luke”), which would be “Wolf” in Germanic countries, where the wolf was an important symbol in European mythology. Wolf also became very popular among Ashkenazis, who usually added the Hebrew translation Ze’ev to the name. The same is true for the classic German/Norse name Baer (“Bear”), to which Ashkenazis added Dov, its Hebrew translation. None of these names are Biblical or Talmudic, nor is their origin truly Hebrew. (Ironically, the name Ze’ev appears in the Tanakh [Judges 7:25] as the name of an enemy Midianite prince that the Israelites slayed!)

Having said that, many have linked these names to Biblical characters. For example, Benjamin is described in the Torah as a wolf (Genesis 49:27), so some carried the name “Binyamin Wolf”, where the former was their actual Jewish name while the latter was their social name. The same goes for “Yehuda Leib”, where Leib means “lion”, like Aryeh, the symbol of the Biblical Yehuda. It has even become common to combine all three to form “Yehuda Aryeh Leib”. Similarly, there’s “Naftali Tzvi Hirsch”, since the Biblical Naftali is described as a deer, ayalah or tzvi, and “Hirsch” is German for “deer”.

A portrait thought to be of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the “Alter Rebbe” (1745-1812). For more on the origins of this portrait, see here.

“Schneur”, too, is of non-Jewish origin, and comes from the Spanish name Senor (and is sometimes a German equivalent for Seymour). Chassidim have since reinterpreted it in the Hebrew as Shnei Or, “two lights”. It probably didn’t have this meaning when it was given to Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder and first rebbe of Chabad. In his case, “Schneur” was likely meant to be his social name while “Zalman” (Solomon, or “Shlomo”) was his traditional Jewish or Hebrew name.

Sephardic Jews are just as culpable. Many have Arabic names like “Massoud” (which means “lucky”) or “Abdullah”. In fact, Rav Ovadia Yosef’s birth name was Yusuf Abdullah, and it was only when the family made aliyah to Israel that “Abdullah” was replaced with its Hebrew translation “Ovadia” (which is a Biblical name). At one point, a popular female Sephardic name was “Mercedes”. This one is highly problematic, as it happens to be a Spanish appellation for the Virgin Mary! (The automobile brand Mercedes is named after a Jewish girl of that name, the daughter of the company’s founder Emil Jellinek and his French-Sephardi wife.) A similar problem lies with the very popular “Natalie”, which literally means “Christmas” in Latin.

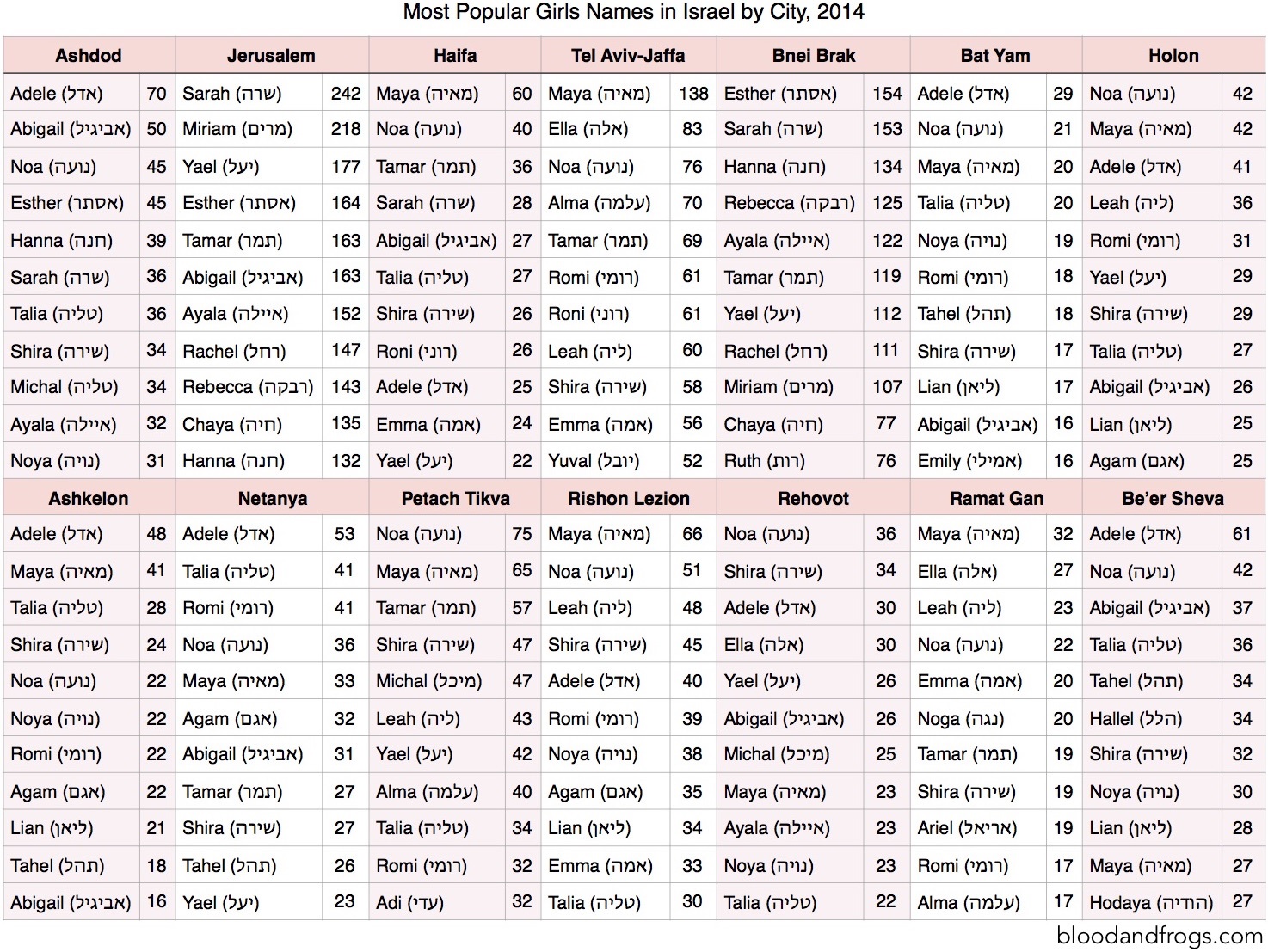

Is it okay to bear such names? A distinction must be made between those that clearly have an idolatrous origin versus those that were simply adapted from non-Jewish names but still carry a good meaning. The latter are certainly permissible, since many of our great Sages had such foreign names. Over time, many of these evolved a deeper, Jewish meaning. For instance, Adele was a classic German name (meaning “noble”) and yet the Baal Shem Tov chose it for his daughter. He explained to his chassidim that he received this name through divine inspiration, and that it is an acronym (אדל) for the important words in the Torah אש דת למו—that God gave His people “a fiery Torah” (Deuteronomy 33:2). The Torah, like fire, purifies all things. The Baal Shem Tov’s daughter went on to become a holy chassid of her own, imbued with so much Ruach haKodesh that she was nicknamed Adele HaNeviah, “Adele the Prophetess”.

Jewish “Non-Jewish” Names

The opposite case exists as well: names that appear to be non-Jewish but actually have a clear Jewish origin. Take “Elizabeth”, for example. While it may sound like a classic European name, it is actually the transliteration of “Elisheva” (אלישבע), the righteous wife of Aaron (Exodus 6:23). Some Jewish name sources incorrectly write that John is a non-Jewish name, associating it with the “New Testament” John. Yet, even that John was originally a Jewish man living in Israel, and “John” is simply a transliteration of the Hebrew name “Yochanan”. (It sounds closer in Germany and Eastern Europe, where “John” is “Johan”, or “Yohan”.)

There are numerous other examples. Susanna is Shoshana (שושנה), and Abigail is Avigayil (אביגיל). In the Tanakh, the latter makes an important comment about names, pointing out that because her first husband’s name was Naval (“abomination”) he acted abominably (I Samuel 25:25). She later married King David and is considered a prophetess in her own right.

Many are surprised to discover that “Jessica” comes from the Torah. It is an English adaptation of Iscah (יסכה), mentioned in Genesis 11:29 and, according to our Sages, the birth name of Sarah. Rashi comments:

Iscah. This is Sarah, because she would see [סוֹכָה] through divine inspiration, and because all gazed [סוֹכִין] at her beauty. Alternatively, יִסְכָּה is an expression denoting princedom [נְסִיכוּת], just as Sarah is an expression of dominion [שְׂרָרָה].

Interestingly, it appears that the earliest recorded use of the transliteration “Jessica” comes from Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice. Here, Jessica is the Jewish daughter of the play’s Jewish villain, Shylock. Although many see The Merchant of Venice as an anti-Semitic work, others actually see it as Shakespeare’s cunning manipulation of that era’s rampant anti-Semitism and his own “plea for tolerance”. After all, Shylock’s most famous speech (Act III, Scene 1) reads:

Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal’d by the same means, warm’d and cool’d by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that.

Shylock argues that his own villainy is nothing but a reflection of the villainy of the Christian world. Shakespeare recognized the cruelty that Jews had suffered, and tells his anti-Semitic audience that Jews are human, too.

Is It Necessary to Have a Hebrew Name?

Ultimately, it is certainly beneficial to have a Hebrew name of some sort, whether Biblical, Talmudic, adapted, or modern. After all, Hebrew is a holy language, and each of its letters carry profound meaning. The Hebrew term for “name” is shem (שם), which is a root of neshamah (נשמה), “soul”, and spelled the same as sham (שם), “there”, for it is there within a person’s name that his or her essence is found. For this reason, the Talmud (Yoma 83b) tells us that Rabbi Meir used to carefully analyze people’s name to determine their character. (This Talmudic passage was explored at length in Secrets of the Last Waters.)

The Talmud (Rosh Hashanah 16b) also notes that changing one’s name is one of five things a person can do to change their fate. Indeed, we see this multiple times in Scripture. Abraham and Sarah have their names changed (from Abram and Sarai) to allow them to finally have a child. Jacob becomes Israel, while Hoshea becomes Yehoshua (Joshua). At some point, Pinchas becomes Eliyahu, and even Yosef (Joseph) becomes Yehosef (Psalms 81:6). On that last name change, the Midrash explains that it was only because Yosef had an extra hei added to his name that he was able to ascend to Egyptian hegemony.

Thus, having a name with a deep meaning, in Hebrew letters, and one that is actually used regularly (as opposed to a secondary Hebrew name that no one calls you by) is of utmost significance. If you don’t yet have such a name, it isn’t too late to get one!

*This Midrash presents a possible contradiction: how can it say that the Israelites did not adopt Egyptian names when we see that some clearly did? Maybe most of the Israelites did not adopt Egyptian names, though some did. Thankfully, another Midrash (Pesikta Zutrati on parashat Ki Tavo) steps in to offer an alternate reason. Here, Israel was redeemed in the merit of three things: not changing their clothing, their food, and their language. Changing their names is conspicuously absent.

The Arizal taught that ever-higher levels of soul are accessed gradually over the course of one’s life. At birth, a person has only a complete nefesh. As they grow, they are infused with ruach, which becomes fully accessible at bar or bat mitzvah age. At this point one starts to tap into their neshamah, which is wholly available only at age 20. (For this reason, the Torah considers an adult one who is over 20 years of age. Only those over 20 were counted in the census and allowed to join the military. Our Sages state that although one may be judged for their crimes before age 20 here on Earth, only those sins accrued after age 20 are judged in Heaven. Meanwhile, the Midrash notes that Adam and Eve were created as 20 year olds.) The Arizal taught that most people never end up accessing their entire neshamah, and only the most refined individuals ever unlock their chayah and yechidah.

The Arizal taught that ever-higher levels of soul are accessed gradually over the course of one’s life. At birth, a person has only a complete nefesh. As they grow, they are infused with ruach, which becomes fully accessible at bar or bat mitzvah age. At this point one starts to tap into their neshamah, which is wholly available only at age 20. (For this reason, the Torah considers an adult one who is over 20 years of age. Only those over 20 were counted in the census and allowed to join the military. Our Sages state that although one may be judged for their crimes before age 20 here on Earth, only those sins accrued after age 20 are judged in Heaven. Meanwhile, the Midrash notes that Adam and Eve were created as 20 year olds.) The Arizal taught that most people never end up accessing their entire neshamah, and only the most refined individuals ever unlock their chayah and yechidah.