This week, outside of Israel, we read the parasha of Acharei Mot. (In Israel, since Pesach is seven days and finished last Friday, Acharei Mot was read on Shabbat and this week the following parasha, Kedoshim, is read. For the next few months, the weekly parasha read in the Diaspora will be different than that read in Israel.) In Acharei Mot, we are commanded:

And any man of the House of Israel or of the foreigner that lives among them, who eats any blood, I will set My countenance upon the soul who eats the blood, and I will cut him off from among his people. For the soul of the flesh is in the blood, and I have therefore given it to you [to be placed] upon the altar, to atone for your souls. For it is the blood that atones for the soul. (Leviticus 17:10-11)

Many recipes call for the use of “kosher salt”. Chefs like it because the larger grains allow them to season their meals more precisely. Jews use koshering salt to remove the tiniest drops of blood that may have remained after draining.

The Jewish people are absolutely forbidden from consuming any kind of blood, whether in a juicy steak or even the tiniest drop inside an egg. It is quite ironic that one of the most disgusting anti-Semitic accusations thrown upon the Jews is that Jews, God forbid, consume the blood of children. (It is all the more ironic that this “blood libel” originates among Catholics who, when taking communion, believe they are drinking the blood of Jesus—who was a Jew!) In reality, Jews obsess over ensuring that we consume no blood whatsoever, and one of the requirements of kosher meat is that all of the blood has been completely removed.

The Torah explains that we should not consume blood because nefesh habasar b’dam hi, the “soul of the flesh is in the blood”. If we eat meat, it is in order to obtain the nutrients in the flesh, not to absorb the spirit of the animal. The animal’s soul is, as the Torah commands, to be placed “upon the altar”. The Kabbalists explain that by doing so, the soul of the animal is allowed to return to the spiritual worlds from which it originates.

In precisely balanced language, the verses cited above state that a Jew who consumes any blood within which is soul, nefesh, will be “cut off” from his nation, and God will personally set His wrath upon that Jewish soul, nefesh. The same word is used to refer to the soul of the Jew and that of the animal. People sometimes forget that animals, too, have souls, and it is forbidden to harm animals in any way.

Having said that, there is of course a great difference between the soul of an animal and the soul of a human. In fact, we find in the Tanakh that five different words are used to refer to the soul. Our Sages explain that a person actually has five souls, or more accurately, five parts or levels to their soul. (The Ba’al HaTurim, Rabbi Yakov ben Asher [1269-1343], states that the five prayer services of Yom Kippur, and the five times that the Kohen Gadol would immerse in the mikveh that day, is in order to purify all five souls; see his commentary on this week’s parasha, Leviticus 16:14.) These five souls are in ascending order, and correspond to the spiritual universes of Creation and to the divine Sefirot. Each soul is itself made up of even smaller, intertwining parts. Understanding the soul and its dynamics is a central part of Jewish mysticism, and what follows is a brief overview of that spiritual map.

The First Three Souls

The first and lowest of the souls is the nefesh. As we have already seen, this soul is associated with the blood, and is the “life force” of a living organism. Above that is the soul called ruach, literally “wind” or “spirit”. We find this term right at the beginning of the Torah (Genesis 1:2) in referring to the Spirit of God (Ruach Elohim) and in many other places to refer to the souls of great people, such as Joshua (Numbers 27:18). Above that is the neshamah, literally “breath”, which we are first introduced to during the creation of Adam, where God breathes a nishmat chayim, “soul of life” into the first civilized man (Genesis 2:7).

The first and lowest of the souls is the nefesh. As we have already seen, this soul is associated with the blood, and is the “life force” of a living organism. Above that is the soul called ruach, literally “wind” or “spirit”. We find this term right at the beginning of the Torah (Genesis 1:2) in referring to the Spirit of God (Ruach Elohim) and in many other places to refer to the souls of great people, such as Joshua (Numbers 27:18). Above that is the neshamah, literally “breath”, which we are first introduced to during the creation of Adam, where God breathes a nishmat chayim, “soul of life” into the first civilized man (Genesis 2:7).

These first three souls—nefesh, ruach, and neshamah; often abbreviated as naran—are spoken of widely across Jewish holy texts, from the Tanakh through the Talmud and the Zohar. For example, the Talmud (Niddah 31a) states how there are three partners in the creation of a person: the father is the primary source of five “white” things (bones, nerves, nails, brain, eyeball), the mother is the primary source of five “red” things (blood, skin, flesh, hair, iris), and God gives ten things, including the ruach and neshamah. (The nefesh presumably goes together with the blood from the mother.)

The Zohar (I, 205b-206a) elaborates that the neshamah is greater than the ruach, which is greater than the nefesh, and that a person only accesses higher levels of their soul if they are worthy. Sinners do not have access to their neshamas at all. They are just living nefesh, like animals. Based on this, the Zohar has a unique perspective on Genesis 7:22-23:

All in whose nostrils was the breath of the spirit of life [nishmat ruach], whatsoever was in the dry land, died. And He blotted out every living substance which was upon the face of the ground, both man, and cattle, and creeping thing, and fowl of the sky; and they were blotted out from the earth; and Noah alone was left, and they that were with him in the ark.

The Zohar sees these two verses as distinct. First, all those people who did merit a ruach and neshamah (meaning they weren’t completely sinful and didn’t deserve to perish in the Flood) died of natural causes. Only after this did God “blot out” all that remained, including animals and people who were so sinful they were essentially like animals, bearing only a nefesh.

With these three souls in mind, many aspects of life can be better understood. For example, when one is asleep only the nefesh remains in the body (to keep it alive), while the higher souls may migrate. This is why a sleeping body is unconscious and likened to a corpse, and why sometimes dreams can be prophetic, as the higher souls may be accessing information from the Heavens, or through interaction with other souls.

Another intriguing example is from Ibn Ezra (Rabbi Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 1089-1167) who relates the three souls to three major purposes of sexual intercourse. The first and simplest is for procreation, something that even animals do, and naturally corresponds to nefesh. The second is for good health, corresponding to ruach. The third is for love and intimacy, fusing the souls of husband and wife, corresponding to the neshamah.

In addition to naran, the Zohar sometimes speaks of additional, even higher souls, such as “nefesh of Atzilut” and “neshamah of Aba and Ima” (see II, 94b). To make sense of these, we must turn to the Arizal.

Earning Your Higher Souls

In multiple places, Rabbi Chaim Vital (1543-1620), the primary disciple of the Arizal (Rabbi Isaac Luria, 1534-1572) and the one who recorded the bulk of his teachings, describes the anatomy of the soul (see, for example, the first passages of Sha’ar HaGilgulim or Derush Igulim v’Yosher 3 in Etz Chaim). At birth, a baby only contains a full nefesh. As the Torah states, the nefesh is in the blood, and the Arizal adds that since the liver filters blood and is full of it, it is the organ most associated with nefesh. By the age of bar or bat mizvah, a person now has the ability to fully access their ruach. The organ of ruach is the heart (also stated in the Zohar, III, 29b, Raya Mehemna), associated with one’s drives, and both inclinations, the yetzer hatov and the yetzer hara. Only at age 20 does the neshamah become fully available (in most cases). The neshamah is housed in the brain, and is associated with the mind.

Today, we know how scientifically precise those statements are. For example, at any given time the liver (the body’s largest internal organ) contains about 10% of the body’s blood volume, and filters about a quarter of all blood each minute. As well, we know today that the majority of the brain’s development ends around age 20 (though minor changes continue for at least another decade, if not longer). It therefore isn’t surprising that teenagers are so good at making bad decisions. We can also understand why being a teenager is so difficult emotionally, as this is when the ruach is in full force in the heart, and one struggles with their desires and inclinations.

Reinforcing what was said in the Zohar, the Arizal taught that one does not automatically have full access to these souls, but must work on themselves and merit to attain them. Unfortunately, a great many people spend their entire lives stuck in nefesh, living very materialistic and animalistic lives, never overcoming their desires and inclinations (ruach), or achieving any kind of mental greatness (neshamah). The potential is there, though never realized.

For those who do grow ever-higher, they may be able to access even loftier soul levels: the chayah and yechidah. In the Torah, we see many places where the soul is referred to as chayah, including right at the start where God breathes a soul into Adam and makes him l’nefesh chayah (Genesis 2:7). The chayah is sometimes described as an aura. It is not housed within the body, but glows outward, and plays an important role in the interactions between people. (Conversely, some early sources speak of the chayah as being within the body, and serving as its life force. See, for example, Beresheet Rabbah 14:9.)

Above it is the highest level of soul, the yechidah, “singular one”, which connects a person directly with God. It is like a divine umbilical cord, and one who realizes it and senses it may certainly draw through it information from Above. The yechidah, too, has Scriptural basis, for example in Psalms 22:21 and 35:17 where David asks God to save his nefesh and yechidah from danger.

Souls Intertwined With Universes

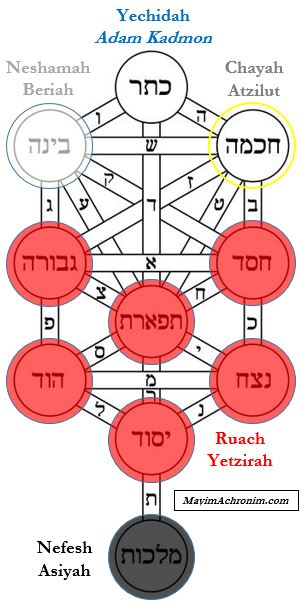

In Etz Chaim, Rabbi Vital cites the Talmud (Berakhot 10a) as the source for the concept of five souls, as well as the five olamot, spiritual universes. (The mystical Sefer HaBahir adds that this is the secret of the letter hei, which has a numerical value of five.) There in the Talmud, the Sages point out how David’s Barchi Nafshi, Psalms 103-104, uses the phrase Barchi nafshi et Hashem, “May my soul bless God” five times. These, the Sages state, correspond to the five olamot, “worlds” or “universes” that David inhabited. Though the Talmud goes on to present a more physical explanation of what these worlds are, it is possible to read deeper between the lines, and the Kabbalists find allusions to five cosmic, spiritual universes, which are: Asiyah, Yetzirah, Beriah, Atzilut, and Adam Kadmon. While explaining these worlds in depth is a topic for another time, we can state that the five souls correspond to these five universes.

In fact, the Arizal teaches that one can identify the soul elevation of another by studying the colour of their aura: black is the colour of Asiyah, the lowest, physical realm which we visibly inhabit. The higher world of Yetzirah, the domain of angels and spirits, is red. Even higher is Beriah, literally “Creation”, where the very spiritual foundations of Creation exist. It is white. Above this is Atzilut, “divine emanation”, which is pure, brilliant light. These worlds, and souls, correspond to the letters of God’s Name. The final hei is Asiyah/Nefesh, the vav is Yetzirah/Ruach, the first hei is Beriah/Neshamah, the yud is Atzilut/Chayah, and the “crown” atop the yud is Adam Kadmon/Yechidah.

How the letters of God’s Ineffable Name relate to the five levels of soul, the five “universes”, and the Ten Sefirot. (Zeir Anpin refers to the middle six Sefirot from Chessed to Yesod.)

All of these also correspond to the major branches of Torah study. Learning Tanakh is in Asiyah, while Mishnah is in Yetzirah. Talmud is in Beriah, while Kabbalah is in Atzilut. When one learns these texts, they are putting on a spiritual “garment” for that soul level, rectifying it and elevating it further, and this garment will remain with them in the World to Come (see Sha’ar HaPesukim on Tehilim). This is the deeper meaning of Psalm 19:8, which states that God’s Torah is temimah, meshivat nafesh, is “pure and restores the soul”.

Adam Kadmon is left out of the above (and in general is made distinct from the other four universes) because that level is where one has mastered all of the Torah branches, has refined their soul to the highest degree, and is a perfectly righteous person. This level may be equated to the super-lofty soul of Nefesh d’Atzilut which we previously mentioned from the Zohar. Such a rare person is referred to as a malakh, an “angel”, and this was the case with people like Eliyahu, Yehudah, Hezekiah, and Enoch (Sha’ar HaGilgulim, ch. 39).

How the souls and universes relate to the “Tree of Life” which depicts the 32 Paths of Creation – the 10 Sefirot and the 22 Hebrew letters.

Emptying The Universe’s Soul

In case it wasn’t complicated enough just yet, the Arizal taught that each of the five souls is itself composed of five souls. So, within the nefesh, ruach, neshamah, chayah, and yechidah (abbreviated as naran chai) there is an inner nefesh, ruach, neshamah, chayah, and yechidah! That makes 25 smaller parts to the soul. Furthermore, each of these parts is composed of 613 sparks corresponding to the 613 mitzvot. Each of those sparks is further composed of 600,000 even smaller sparks. Multiplying them all together, we get 9.195 billion sparks.

In the same place where he writes this (Sha’ar HaGilgulim, ch. 11), Rabbi Vital explains that all of these sparks were contained within Adam. We may assume that it probably isn’t the case that each person has 9 billion or more sparks, but that Adam’s original soul divided up into so many sparks. Since it is said that in the same way all people are physical descendants of Adam, they are also his spiritual descendants, we might conclude that the world should expect to have a population of up to 9.195 billion people. Interestingly, demographers are currently predicting that Earth’s population will actually top out around 9 billion, and will then start to decline. This prediction is quite amazing in light of one famous Talmudic teaching:

In Yevamot 62a, the Sages state that Mashiach will not come until all souls are born. They describe a Heavenly repository of souls called Guf, literally “body”. Only when Guf is empty can Mashiach arrive. The Guf may be mystically referring to that first “body” of Adam which contained all souls within it. Once all of those sparks are born, all souls from the beginning of time will be alive simultaneously so that everyone can witness the tremendous Final Redemption. It appears we are inching ever closer to that moment.

The above essay is adapted from Garments of Light, Volume Three.

Get the book here!

For more about soul dynamics, see the following:

The Muslim Mamluks did not draw any faces on their court cards (since depicting faces in art is forbidden in Islam). The Europeans did not have this issue, and adapted the Muslim court cards of malik (king), malik na’ib (deputy king), and thani na’ib (second deputy) to king, queen, and prince or knight (“jack”). In 16th century France, the four kings were depicted as particular historical figures: the King of Spades was King David, the King of Clubs was Alexander the Great, the King of Hearts was Charlemagne, and the King of Diamonds was Julius (or Augustus) Caesar.

The Muslim Mamluks did not draw any faces on their court cards (since depicting faces in art is forbidden in Islam). The Europeans did not have this issue, and adapted the Muslim court cards of malik (king), malik na’ib (deputy king), and thani na’ib (second deputy) to king, queen, and prince or knight (“jack”). In 16th century France, the four kings were depicted as particular historical figures: the King of Spades was King David, the King of Clubs was Alexander the Great, the King of Hearts was Charlemagne, and the King of Diamonds was Julius (or Augustus) Caesar.