This week’s parasha begins with the passing of Sarah, the first Matriarch. We read how Abraham “eulogized Sarah and bewailed her” (Genesis 23:2). Today, the ritual most associated with Jewish death and mourning is undoubtedly the recitation of Kaddish. This has become one of those quintessentially Jewish things that all Jews—regardless of background, denomination, or religious level—tend to be very careful about. It is quite common to see people who otherwise never come to the synagogue to show up regularly when a parent or spouse dies, only to never be seen again as soon as the mourning period is over. Kaddish has become so prevalent that it has gone mainstream, featured in film and on TV (as in Rocky III and in the popular Rugrats cartoon), on stage (in Angels in America and Leonard Bernstein’s Symphony no. 3), and in literature (with bestselling novels like Kaddish in Dublin, and Kaddish For an Unborn Child).

Sylvester Stallone, as Rocky Balboa, recites Kaddish for his beloved coach and mentor.

And yet, the origins of Kaddish are entirely clouded in mystery. It isn’t mentioned in the Tanakh, nor is there any discussion of reciting Kaddish for the dead in the Mishnah or Talmud. Even in the Rambam’s monumental Jewish legal code, the Mishneh Torah—just over 800 years old—there is no discussion of a Mourner’s Kaddish. Where did it come from?

Praying for Redemption

The Talmud refers to Kaddish in a number of places (such as Berakhot 3a, for example), though not in association with mourning the dead. Around the same time, we see a prayer very similar to Kaddish in the New Testament (Matthew 6:9-13), which has since become known as the “Lord’s Prayer” among Christians. This suggests that Kaddish existed before the schism between Judaism and Christianity, and this is one reason scholars date the composition of Kaddish to the late Second Temple era.

Many believe that it was composed in response to Roman persecution. The text of the Kaddish makes it clear from the very beginning that it is a request for God to speedily bring about His great salvation. It certainly makes sense that such a prayer would be composed in those difficult Roman times. In fact, the first words of Kaddish are based on Ezekiel 38:23, in the midst of the Prophet’s description of the End of Days (the famous “Gog u’Magog”), where God says v’itgadalti v’itkadashti. The Sages hoped the travails they were struggling through were the last “birth pangs” of the End Times.

In Why We Pray What We Pray, Barry Freundel argues that Kaddish was originally recited at the end of a lecture or a Torah learning session—as continues to be done today. It likely came at a time when public Torah learning or preaching was forbidden, as we know was the case in the time of Rabbi Akiva. So, the Sages ended their secret learning sessions with a prayer hoping that the Redemption would soon come, and they would once more be able to safely preach in public.

If that’s the case, how did Kaddish become associated with mourning the dead?

The Mourner’s Kaddish

Freundel points out that the earliest connection between Kaddish and the souls of the dead is from the Heikhalot texts. These are the most ancient works of Jewish mystical literature, going as far back as the early post-Second Temple era. (Scholars date the earliest texts to the 3rd century CE). One of these texts reads:

In the future, the Holy One, blessed be He, will reveal the depths of Torah to Israel… and David will recite a song before God, and the righteous will respond after him: “Amen, yehe sheme rabba mevorach l’olam u’l’olmei olmaya itbarach” from the midst of the Garden of Eden. And the sinners of Israel will answer “Amen” from Gehinnom.

Immediately, God says to the angels: “Who are these that answer ‘Amen’ from Gehinnom?” [The angels] say before Him: “Master of the Universe, these are the sinners of Israel who, even though they are in great distress, they strengthen themselves and say ‘Amen’ before You.” Immediately, God says to the angels: “Open for them the gates of the Garden of Eden, so that they can come and sing before Me…”

The Heikhalot connect Kaddish (specifically its central verse, “May His great Name be blessed forever and for all eternity…”) to a Heavenly prayer that will be recited at the End of Days, when the souls in Gehinnom will finally have reprieve. We can already start to see how this might relate to mourning, or spiritually assisting, the recently deceased.

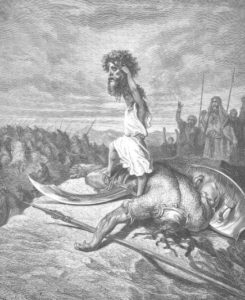

This is related to another well-known story that is by far the most-oft used as the origin of Kaddish. In this narrative, a certain great sage—usually Rabbi Akiva, but sometimes Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai—sees a person covered in ash and struggling with piles of lumber. The poor person explains that he is actually dead, and his eternal punishment (reminiscent of popular Greek mythology) is to forever gather wood, only to be burned in the flames of that wood, and to repeat it all over again. The Sage asks if there is anything he could do to help, to which the dead man replies that if only his son would say a particular prayer, he would be relieved of his eternal torment.

The nature of that prayer varies from one story to the next. In some, it is the Shema, in others it is Barchu, and in others it is a reading of the Haftarah (see, for example, Kallah Rabbati 2, Machzor Vitry 144, Zohar Hadash on Acharei Mot, and Tanna d’Vei Eliyahu Zuta 17). It is only in later versions of the story that the prayer the son must say is Kaddish. Whatever the case, between the Heikhalot texts, and these Midrashic accounts, we now have a firm connection linking Kaddish with the deceased.

I believe there is one more significant (yet overlooked) source to point out:

The most important part of the Kaddish is undoubtedly the verse yehe sheme rabba mevorach l’olam u’l’olmei olmaya. As we saw in the Heikhalot above, this is the part that especially arouses God’s mercy. The Talmud (Berakhot 3a) agrees when it says essentially the same thing about the entire congregation reciting aloud “yehe sheme hagadol mevorach”. These special words are based on several Scriptural verses, such as Psalm 113:2 and Daniel 2:20. It also appears in Job 1:21.

Here, Job suffers the death of all of his children. Upon hearing the tragic news, he famously says: “…naked I came out of my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return; the Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away; blessed be the name of the Lord.” In Hebrew it reads: Adonai natan, v’Adonai lakach, yehi shem Adonai mevorach. The parallel is striking. The first person in history to recite the great “yehe sheme rabba” upon the death of a family member is none other than Job. In some way, Job may be the originator of the Mourner’s Kaddish.

Birth of a Custom

Officially, the earliest known mention of reciting Kaddish for the dead is Sefer HaRokeach, by Rabbi Elazar of Worms (c. 1176-1238). Shortly after, his student Rabbi Itzchak of Vienna (1200-1270) writes in his Ohr Zarua that Ashkenazim have a custom to recite Kaddish upon the dead. He explicitly states that Tzarfati Jews (and as an extension, Sephardic Jews) do not have such a custom.

That much is already clear from the Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1135-1204), the greatest of Sephardic sages in his day, who makes no mention of a Mourner’s Kaddish anywhere in his comprehensive Mishneh Torah. (The Rambam does speak about the regular Kaddish, unrelated to the dead, which is recited throughout the daily prayers.) We see that in his time, Kaddish was still a strictly Ashkenazi practice. Why is it that Ashkenazi Jews in particular began to say Kaddish for the dead?

Most scholars believe the answer lies within the Crusades. The First Crusade (1095-1099) was a massive disaster for Europe’s Ashkenazi Jews. While the Crusades were meant to free the Holy Land from Muslim domination, many local Christians argued that there was no need to fight the heathen all the way in the Holy Land when there were so many local Jewish “heathens” among them. The result is what is referred to as “the Rhineland massacres”, described by some as “the First Holocaust”. Countless Jews were slaughtered.

‘Taking of Jerusalem by the Crusaders, 15th July 1099’ by Émile Signol

Like in the times of Roman persecution a millennium earlier, the Ashkenazi Sages sought comfort in the words of Kaddish, beseeching the coming of God’s Final Redemption, and at the same time seeking to honour the poor souls of the murdered. It therefore isn’t surprising that Rabbi Elazar of Worms is the first to speak of Kaddish for the dead, as his hometown of Worms (along with the town of Speyer) was among the first to be attacked, in May of 1096.

It is important to remember that Rabbi Elazar was a member of the Hasidei Ashkenaz, the “German Pietist” movement known for its mysticism and asceticism (not to be confused with the much later Hasidic movement). The Hasidei Ashkenaz would have been particularly well-versed in Heikhalot and Midrashim. Everything points to this group as being the true originators of reciting Kaddish for the dead.

The practice spread from there. Indeed, there was a great deal of Jewish migration in those turbulent times. For example, one of the greatest Ashkenazi sages, Rabbeinu Asher (c. 1250-1327), was born in Cologne, Germany, but fled persecution and settled in Toledo, Spain. His renowned sons, Rabbi Yakov ben Asher (Ba’al HaTurim, c. 1269-1343), and Rabbi Yehudah ben Asher (c. 1270-1349) continued to lead the Sephardic Jewish community of Toledo. And it was there in Toledo that was born one of the greatest of Sephardi sages, Rabbi Yosef Karo (1488-1575), author of the Shulchan Arukh, still the primary code of Jewish law.

In the Shulchan Arukh we are only told to recite Kaddish once at a funeral, following the burial (Yoreh De’ah 376:4). It is in the gloss to the Shulchan Arukh by the Ashkenazi Rama (Rabbi Moshe Isserles, 1530-1572) where we find that it is customary to continue reciting Kaddish for twelve months, though only for a parent, based on Midrashim that speak of reciting Kaddish for a father. The reasoning for the latter is that, since it is a father’s obligation to teach his son Torah, by reciting Kaddish the son demonstrates that the father had fulfilled the mitzvah, and left behind a proper Jewish legacy.

It is quite amazing to see that as late as 500 years ago, Mourner’s Kaddish was still defined in very narrow terms, and described as more of a custom (especially for Ashkenazim) based on Midrash than an absolute halachic necessity. How did it transform into a supreme Jewish prayer?

Enter the Arizal

As with many other Jewish practices we find so common today, it looks like it was the influence of the Arizal (Rabbi Isaac Luria, 1534-1572), history’s foremost Kabbalist, that made the Mourner’s Kaddish so universal, and so essential. Fittingly, he was the perfect candidate for the job, being the product of an Ashkenazi father and a Sephardi mother, and ending his life as the leader of the Sephardi sages of Tzfat.

The Arizal discussed the mysteries of Kaddish at great length. Like most of his teachings, they were put to paper by his primary disciple, Rabbi Chaim Vital (1543-1620). The latter devotes a dozen dense pages to Kaddish in Sha’ar HaKavanot. He first explains the various forms of Kaddish recited during the regular prayer services. In brief, we find that Kaddish is recited between the major prayer sections because each part of the prayer is associated with a different mystical universe, and a different Heavenly Palace, and Kaddish facilitates the migration from one world to the next.

Recall that Kabbalah describes Creation in four universes or dimensions: Asiyah, Yetzirah, Beriah, and Atzilut. The four sections of prayer correspond to the four ascending universes: the morning blessings and the first prayers up until Hodu correspond to Asiyah; the Pesukei d’Zimrah corresponds to Yetzirah; the Shema and its blessings parallel Beriah; and the climax of the prayer, the Amidah, is Atzilut, the level of pure Divine Emanation. For this reason, the Amidah is recited in complete silence and stillness, for at the level of Atzilut, one is entirely unified with God.

The Arizal delves in depth into the individual letters and gematrias of Kaddish, its words and phrases, and how they correspond to various names of God and Heavenly Palaces. He relays the proper meditations to have in mind when reciting the different types of Kaddish, at different stages of prayer. To simplify, the Arizal teaches that Kaddish helps us move ever higher from one world to the next, and more cosmically, serves to elevate the entire universe into higher dimensions. We can already see how this would be related to assisting the dead, spiritually escorting the soul of the deceased higher and higher through the Heavenly realms.

More intriguingly, Rabbi Vital writes that Kaddish is meant to prepare the soul for the Resurrection of the Dead. He goes on to cite his master in saying that Kaddish should be recited every single day, including Shabbat and holidays, for an entire year following the passing of a parent. He says that Kaddish not only helps to free a soul from Gehinnom, but more importantly to help it attain Gan Eden. It elevates all souls, even righteous ones. This is why one should say Kaddish for a righteous person just as much as for a wicked person, and this is why it should be said even on Shabbat (when souls in Gehinnom are given rest). Rabbi Vital then says how the Arizal would also say Kaddish every year on the anniversary of his father’s death, which is now the norm as well.

Ironically, while Kaddish began as an Ashkenazi custom, Rabbi Vital writes that the Arizal made sure to recite Kaddish according to the Sephardi text!

Repairing the World

Another interesting point that Rabbi Vital explains is why Kaddish is in Aramaic, and not Hebrew like the rest of the prayers. He reminds us the words of the Zohar that both Hebrew and Aramaic are written with the exact same letters because these are the Divine Letters of Creation, but Hebrew comes from the side of purity and holiness, while Aramaic is from the “other side” of impurity and darkness. Hebrew is the language of the angels, while Aramaic is the language of the impure spirits. The angels speak Hebrew, but do not understand Aramaic, while their antagonists speak Aramaic, and do not understand Hebrew. When we learn Torah and Mishnah, in Hebrew, we please the angels who take our words up to Heaven. When we learn Talmud and Zohar, in Aramaic, we destroy those dark spirits who cannot stand the fact that a person is using their tongue for words of light and holiness.

The same applies to our prayers. The bulk of our prayers are in holy Hebrew, the language of angels. Kaddish is in Aramaic because it is meant to elevate us, and the universe around us, into higher dimensions. In this vital task, we cannot risk elevating the impure spirits along with us, contaminating the upper worlds. Thus, by saying it in Aramaic, we push away the impure spirits who are unable to withstand us using their language in purity. Those evil forces are driven away, and we can ascend and rectify in complete purity.

This, in brief, is the tremendous power of Kaddish. This is why we recite it so many times over the course of the day. And this is why every Jew is so mysteriously drawn to this prayer and ritual, possibly above all others. Deep inside the soul of every Jew—regardless of background, denomination, or religious level—is a yearning to repair the world, to destroy the impure, to uplift the universe, and to recite loudly: “May His great Name be blessed forever and for all eternity…”